Early congenital syphilis

Jihad Kassel , Hanane Baybay, Chaymae Jroundi, Sara Elloudi, Zakia Douhi, Fatima-Zahra Mernissi

, Hanane Baybay, Chaymae Jroundi, Sara Elloudi, Zakia Douhi, Fatima-Zahra Mernissi

Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Hassan II, Fes, Morocco

Corresponding author: Jihad Kassel, MD

Submission: 27.10.2021; Acceptance: 28.02.2022

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.2022e.17

Cite this article: Kassel J, Baybay H, Jroundi C, Elloudi S, Douhi Z, Mernissi FZ. Early congenital syphilis. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(e):e17.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease. Infants can become infected via transplacental transmission from an infected mother during any stage of a pregnancy. It can be associated to premature delivery, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, nonimmune hydrops, perinatal death. Recognition of congenital syphilis is difficult because clinical presentation is diverse and often non-specific. We report a new case of early congenital syphilis.

Key words: Syphilis, Pregnancy, Infection, Child

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum sub- species pallidum, which belongs to the family Treponemataceae. It has direct adverse effects on maternal and infant’s health through vertical Treponema pallidum transmission during early pregnancy [1]. Congenital Syphilis (CS) can be avoided with appropriate maternal diagnosis and treatment during the pregnancy. Diagnosing CS and determining the therapeutic course can be challenging [2]. Maternal management is based on the early administration of penicillin, the management of the child is based on diagnosis and early treatment with parenteral penicillin [3].

CASE REPORT

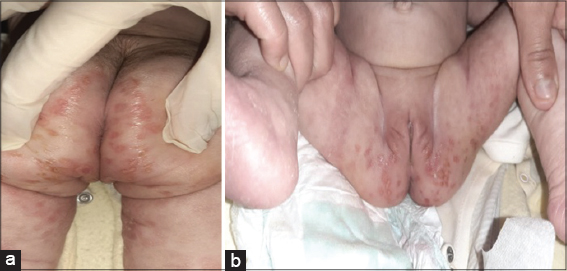

A two-month- old girl was presented at the emergency room for a febrile rash. She was born at term with a 3 kg birthweight via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a 25-year-old primigravida mother with no pregnancy follow-up. The infant was well vaccinated with exclusive breastfeeding. The symptomatology goes up to one month with the appearance of erythematous lesions in the neck and perineum which subsequently became general. It pushes the mother to proceed for traditional treatments without improvement. It evolves in a context of unspecified fever, cough, rhinitis and diarrhea. On admission, the patient’s temperature was at 37.8°C, and vital signs were within normal ranges. Physical examination showed a rhinitis with pseudomembranes in the oral mucosa, crusty perioral fissure (Fig. 1) fibrinous ulceration in the buttocks and perineum (Fig. 2ab), associated with slightly scaly erythematous lesions surrounded by a peripheral collar at the level of the limbs. We also noted abdominal distention. The clinical examination was suggesting either atopic/seborrheic dermatitis with bacterial and viral infection or enteropathy acrodermatitis, we have also thought about early congenital syphilis especially since the pregnancy was not followed, and also Because of the presence of rhinitis and perioral fissure. Complete blood count showed anemia (6,2 mmol/L) and thrombocytopenia (118 103/uL) with elevated leucocytes (14,81 103/uL), CRP (16 mg/L), and positive syphilitic serology. Blood testing of the mother showed positive treponemal results with TPHA=1/1280, VDRL= 1/16. Lumbar puncture and X-Rays of long bones was normal. We put the patient on ampicillin for 10 days, after concertation with the pediatricians given that the penicillin G IV was not available. The evolution was good with the disappearance of skin lesions (Figs. 3a and 3b), we also treated the mother after a normal clinical examination we requested syphilitic serology from the dad who refused to perform it.

DISCUSSION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, it can lead to chronic and systemic infectious disease affecting several organs, including skin and mucous membranes. Contact with genital syphilitic lesions is responsible for 95% of syphilis cases [1]. Infants can become infected via transplacental transmission from an infected mother during any stage of a pregnancy [2]. The incidence of congenital syphilis appears to be decreasing in several countries with the introduction of preventive prenatal screening recommended by the WHO, despite this, there is an increase in global incidence rates even in high-income countries. During pregnancy, it is associated with premature delivery, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, nonimmune hydrops, perinatal death [3]. CS is divided into early and late disease based on results that appear before or after the age of 2 years. Early CS is typically present in the neo-natal period within the first 4 to 8 weeks. More than half (60–90%) of liveborn infants are asymptomatic at birth, with first clinical signs presenting by the age of 3 months [4]. Mucocutaneous lesions are prominent manifestations that occur in 40–60%, it manifests by a maculopapular rash witch becomes copper-colored with desquamation mostly in the palms and soles, a bullous rash known as syphilitic pemphigus may develop with peeling and possibly scabs and wrinkles in the skin. Rhinitis (“snuffles”), a nasal discharge that is initially watery but may become thick, purulent, and blood-tinged. Rarely, cracking of the lips covered with scabs, plaques of the tongue and palate as well as white, flat, moist, raised patches called condylomata lata in the perioral and perianal areas [5]. Other clinical findings may include hepatomegaly lymphadenopathy, pneumonia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, osteochondritis, and pseudoparalysis [2]. Ocular findings (chorioretinitis, cataract, glaucoma, and uveitis), gastrointestinal tract leading to malabsorption and diarrhea. The diagnosis of congenital syphilis is established by the observation of spirochetes in body fluids or tissue and suggested by serologic test results [4].

Non treponemal testing should be performed on all infants with suspected CS and should involve the same nontreponemal test performed on the mother for direct comparison. A four-fold difference in the mother versus infant titers is suggestive of CS [2]. Brain damage is found in 50% of probable or confirmed cases of congenital syphilis, justifying the systematic performance of LP. In this context, in search of a neuro syphilis [3], methods and definitions tend to differ internationally. Some countries rely on a four-fold increase in IgM titers to diagnose congenital syphilis [5]. The treatment is based on penicillin G IV 150,000 U/kg/day (in 6 doses every 4 hours) for 10 days (14 days if neurosyphilis) [3]. Research efforts are urgently needed to assess whether other antibiotics such as ampicillin can effectively treat congenital syphilis on children with history of penicillin allergy or in countries where penis G is not available, Recently, there has been an acute shortage of penicillin world- wide [6]. All pregnant women should have a serologic test for syphilis performed at the first prenatal visit in the first trimester [5], Screening for syphilis at the first antenatal visit is the standard of care, but may not detect late acquisition of maternal infection, In high risk populations, rescreening for syphilis should be performed during pregnancy both early in the third trimester and again at delivery [7].

CONCLUSION

Congenital syphilis is a severe infection which can have serious consequences on infants and children, it is effectively prevented by prenatal serologic screening of mothers and penicillin treatment of infected women, their sexual partners, and their newborn. Through this case we insist on the importance of serological screening in the mother during pregnancy and also on the interest of recognizing clinical signs which are very evocative of this diagnosis.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Bezerra MLMB, Fernandes FECV, de Oliveira Nunes JP, de Araújo Baltar SLSM, Randau KP. Congenital Syphilis as a Measure of Maternal and Child Healthcare, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:1469-76.

2. Kwak J, Lamprecht C. A review of the guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of congenital syphilis. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:e108-14.

3. Arrieta AC, Singh J. Congenital Syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2157.

4. Keuning MW, Kamp GA, Schonenberg-Meinema D, Dorigo-Zetsma JW, van Zuiden JM, Pajkrt D. Congenital syphilis, the great imitator-case report and review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e173-9.

5. Cooper JM, Sánchez PJ. Congenital syphilis. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42:176-84.

6. Agarwal A, Kumar J. Congenital Syphilis Resurgences and Penicillin Shortage. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:959-60.

7. O’Connor NP, Gonzalez BE, Esper FP, Tamburro J, Kadkhoda K, Foster CB. Congenital syphilis:Missed opportunities and the case for rescreening during pregnancy and at delivery. IDCases. 2020;22:e00964.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X |

Comments are closed.