Skin diseases in the world`s indigenous peoples – with special focus on Greenland’s Inuit`s population

Carsten Sauer Mikkelsen 1,2, Casper Bo Poulsen3,4, Peter Bjerring5, Lone Storgaard Hove6

1,2, Casper Bo Poulsen3,4, Peter Bjerring5, Lone Storgaard Hove6

1Private Practice in Dermato-Venereologi, Brønderslev, Denmark, 2Senior Research Fellow, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, 3AUH Emergency Department, Aarhus, Denmark, 4Department of Dermatology, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, 5Department of Dermatology, Aalborg University Hospital, Mølholm Hospital A/S, Denmark, 6Dermatology, Dronning Ingrids Sundhedscenter, Nuuk, Greenland

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2024. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Providing health care in Greenland is a major challenge. Spanning 2,600 km from north to south and 1,050 km from east to west, Greenland is the largest island in the world and has the lowest population density on the globe. The geographical situation combined with, at times, extreme weather conditions make providing healthcare a logistical challenge in Greenland. Most Doctors working in Greenland are used to perform a very broad range of medical duties including various dermatological conditions. But not a single certified Dermato-venereologist at work in Greenland. Dermatological care at specialist level is provided by tele-dermatology. In this article we will describe some of the problems with skin diseases in Greenland with special focus on the Inuit population – based on challenges with access to care and challenges associated with diagnosis based on differences in baseline patient characteristics and correct treatment due to cultural differences influencing treatment preferences.

Key words: Arctic dermatology, Inuits, Atopic dermatitis, Psoriasis, Hidradenitis Suppurativa

INTRODUCTION

Dictionaries define indigenous as “originating in a particular region or country”.

The word dates all the way back to the Latin word “indigena “, meaning native or original inhabitant.

Due to the diversity and difficult history experienced by these groups, including countries that don’t recognize indigenous peoples in their lands, there is purposefully no official definition of “indigenous people”.

The UN and other organizations working with indigenous peoples utilize an understanding based on self-determination that includes:

- Self-identification as indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community.

- Historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies.

- Strong link to territories and surrounding resources.

- Distinct social, economic, or political systems.

- Distinct language, culture, and beliefs.

- Forms non-dominant groups of society.

- Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems.

Groups like Greenland’s Inuit were included, because of their long history of colonial control as well as Danish influence.

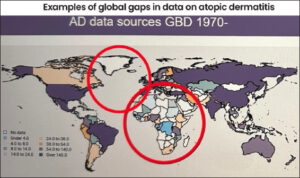

This above map by “Bhabna Banerjee” (Fig. 1) uses data from the indigenous World 2010-2022 report to show the population distribution of the roughly 476 million Indigenous people around the world.

Please notice (according to the map) Greenland is a country territory with one of the largest shares of indigenous people with 89 % of Inuit ethnicity.

It is already evidence based that skin diseases are highly prevalent among indigenous people and greatly impacting their quality of life.

Unfortunately, skin diseases among indigenous populations have only been very poorly described in the literature [1].

Only few data on racial and ethnic differences in skin and hair structure, physiology, and function exist [2].

In the following we will focus on some of the most prevalent dermatological diseases among intuits in Greenland and the challenges because of few doctors in general in the country and no dermatologist at all working permanently in the region.

Providing health care in Greenland is a major challenge. Spanning 2,600 km from north to south and 1,050 km from east to west, Greenland is the largest island in the world [3,4]. Greenland has the lowest population density on the globe. The current population of Greenland in 2022 totals 56,466 inhabitants, and 19,394 people live in Nuuk alone. The majority of the population is of Greenlandic origin, while 2.4% are immigrants from the Philippines, Thailand, and Iceland. People live along the coastline, as the inner part of Greenland is covered with a permanent ice cap. There are 18 “larger” settlements and 120 small villages. No roads exist between these settlements, and travelling between settlements require transportation by helicopter, airplane, boat, snowmobile or sometimes even dog sled [3].

The weather conditions in Greenland can be extreme in wintertime [3]. Since most of the country is located north of the Arctic Circle, and due to the Arctic climate, temperatures regularly fall to –30°C to –40°C and can even drop to as low as –70°C in the coldest places. Besides the cold, Arctic storms, gale winds, heavy fog, and snowstorms can complicate travelling from one city to another.

Greenland’s healthcare system consists of Queen Ingrid’s Hospital in the capital city Nuuk (Fig. 2), and four regional hospitals in the next largest human settlements in Sisimiut, Ilulissat, Aasiaat and Qaqortoq. There are 13 physician-staffed health clinics/small hospitals and 48 rural health clinics staffed by nurses or healthcare workers in the smallest settlements. Queen Ingrid’s Hospital serves as a referral hospital for the whole country, and the regional hospitals serve as referral hospitals for the smallest hospitals [5].

|

Figure 2: The healthcare system in Greenland (Photo credit: Carsten Sauer Mikkelsen. Air Photo of Queen Ingrids Hospital in Nuuk) Mikkelsen CS , Poulsen CB, Hove LS. Best Practise Marts 2023. |

In addition to these, the 48 rural health clinics are supervised by physicians and healthcare workers from regional hospitals and small hospitals. Physicians from the regional and small hospitals typically visit the rural settlements two to four times a year. There is an extensive telemedicine service, which allows for medical care to be provided at rural health clinics by a physician daily. This includes both store-and-move-forward applications, as well as live-video telemedical consultations.

The geographical situation combined with, at times, extreme weather conditions make providing healthcare a logistical challenge in Greenland. Physicians in Greenland are used to performing a very broad range of medical duties, the majority probably being within the field of general medicine, general surgery, gynaecology, paediatrics, psychiatry [5].

Physicians also frequently encounter conditions and diseases within the field of dermato-venereology. Dermatological care at specialist level is provided by tele -dermatology. This includes primarily a store-and-move-forward application of clinical photos sent to consultant dermatologists at a Copenhagen University Hospital. There is a provision for sending dermatoscopic images and for live video consultations.

There is also a skin clinic in Nuuk run by a General Practioner with special interest in Dermatology, who is responsible for the overall treatment and coordination of patients throughout Greenland. Now they bring patients in for treatment at the skin clinic in Nuuk to a much greater extent than just few years ago, as a result of the sad fact that there are no permanent working dermatologist and only very few GP`s on the coast outside Nuuk.

In our opinion it is very problematic and many skin diseases including associated co-morbidities can be overlooked and mistreated.

In the following section, we will describe how we feel more doctors and dermatologists in Greenland can make major positive changes within classical dermatology in Greenland, starting with a case from an inuit patient with severe atopic dermatitis.

CLINICAL REPORTS

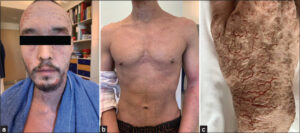

A 25-year-old man has suffered from severe atopic dermatitis since early childhood. In addition, he had experienced a few episodes of acute urticaria. He was not asthmatic, and a skin prick test was negative. He was admitted to the Queen Ingrid’s Hospital in Nuuk with severe infected widespread atopic dermatitis on arrival (Fig. 3a – 3c). Blood samples showed high C-reactive protein values and elevated leukocytes. Cultures turned out positive for staphylococcus aureus. He had no fever. He was treated with intravenous dicloxacillin and penicillin. In addition, he started topical treatment with a combined group III steroid and antibiotic cream together with application moisturizing cream (fat content 70%).

When the infection was cured, the patient continued treatment with daily application of a group IV steroid for 14 days followed by a tapering scheme. He also started high dosage prednisolone (37.5 mg) for 7 days. We took blood samples to be able to start azathioprine or methotrexate, and even discussed the possibility of starting cyclosporine treatment due to the severity of his condition. After 14 days of treatment, the patient’s condition had improved significantly (Figs. 4a – 4c) and additional immunosuppressive treatment was not started.

He was seen at a follow-up visit in the clinic after 3 weeks. Unfortunately, he had not adhered to the prescribed treatment and experienced severe exacerbation of the condition, almost like the condition as seen in Figure 3a – 4c.

DISCUSSION

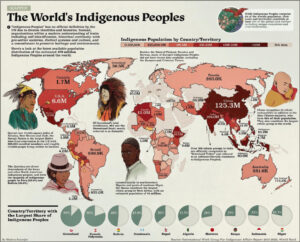

Atopic dermatitis occurs in any geographical location and race, though it appears to be more frequent in urban areas and western countries (Fig. 5). The incidence of atopic dermatitis is increasing worldwide.

|

Figure 5: The global burden of atopic dermatitis: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;184(2):304-309. |

Unfortunately, only a few publications exist about Atopic Dermatitis in Greenland [6–8]. According to GADA (Global Atopic Dermatitis Atlas) gaps in data on atopic dermatitis are comparable with the African continent [9]. GADA is an international collaboration between the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS), the International Eczema Council (IEC), the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis (ISAD), the European Taskforce for Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD), and The Global Alliance of Dermatology Patient Organizations (ADPO/GlobalSkin). GADA aims to make and maintain an atlas where all the data about atopic dermatitis is available, in all countries, answering the questions: how many people have it, at what age, how severe is it, and how is it treated?

The newest research, especially, shows atopic dermatitis is often very severe and has a high prevalence and incidence in Greenland. The most recent study about atopic dermatitis in Greenland showed a surprisingly high point prevalence and cumulative incidence of atopic dermatitis (28.2% and 35.2%) according to physicians’ diagnosis and assessment [10].

In Greenland, there are many interesting aspects regarding the diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis. This primarily involves aspects other than the topical, systemic, or biological treatment of atopic dermatitis. Particularly the importance of patient-centered values and issues.

Proper healthcare consists of clear information and communication with our patients. This is challenging in Greenland’s healthcare system since many healthcare professionals come from abroad, primarily Denmark, and only have short-term contracts. This can result in communication problems between patients and healthcare professionals, who do not speak the Greenlandic Inuit language and are not familiar with Greenlandic culture and practice.

Health professionals often have a different perception of the possibilities within the healthcare system compared with patients. When this perception differs from Greenlandic patients’ knowledge and other considerations about what is possible in their daily lives, this disconnection may have severe consequences for the individual patient’s treatment [11].

Patient Empowerment

Patient empowerment is defined as helping patients to gain control over their own lives and increase their capacity to act on issues that they define as important [12,13]. Patient empowerment is crucial for proper treatment in Greenland, especially regarding the treatment of patients with chronic dermatological diseases. Patients should be encouraged to gain control over their disease: they should learn to take the initiative, solve problems, and make decisions.

These processes can be applied to different settings in healthcare, social care, and self-management [13]. As in other healthcare systems and societies, the shift from a biomedical model to patient-centered care is of the utmost importance in Greenland. This includes several aspects including taking a holistic approach, effective communication, information gathering, reflective listening, and exploration [12].

In addition, sufficient health literacy should be ensured. Patients should be given enough knowledge, understanding, skills, and confidence to use the given health information to take an active role in their wellbeing [11].

It is also important that health professionals actively explore the patients’ own ways of handling their everyday life with illness or disabilities as an indicator of what kind of professional support is meaningful in individual cases. Lone Storgaard Hove and her staff are trying to improve the understanding of atopic dermatitis in the Greenlandic population through the development of the Eczema School called “Kalaallit Nunaat”.

Atopic dermatitis is associated with several co-morbidities such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, autoimmune diseases, alopecia areata, vitiligo, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases (Mb Crohn, colitis ulcerosa) [14].

These co-morbidities emphasize the importance of “patient empowerment” for those with atopic dermatitis and other chronic dermatological diseases in Greenland.

Cold and dry environment as seen in Greenland is a risk factor for increased prevalence of atopic dermatitis. The vast majority of patients require topical treatment with steroids and calcineurin inhibitors. Of course, emollient therapy is a must, especially in Greenland. It appeared that there is a possibility to use ultraviolet narrow band (UBV) in atopic dermatitis patients in Nuuk in Greenland and hopefully soon also in other more populated places like Sisimiut, Ilulissat, Asiaat and Qaqortoq. More severe cases are managed with systemic agents, including short courses of steroids, cyclosporine, and for the most severe cases dupilumab. All the participants agreed on the necessity of a holistic approach to this group of patients and the importance of patient education.

Eczema School in Greenland – ”Kalaallit Nunaat Eczema School”

Dermatology area responsible in Greenland, specialized as a GP Lone Hove, her nurse Magdalene Korneliussen, and project manager Tillie Marinussen are busy planning the teaching program and travel program and development of the Eczema School called “Kalaallit Nunaat”. They are working on making educational and socially informative animations films and TV spots, in Greenlandic which will be included in near future teaching.

Psoriasis in Inuit populations from Greenland

Very few studies describe the prevalence and incidence of psoriasis among Inuit populations [15,16]. Higher prevalence rates have been reported at higher latitudes, and also in Caucasians compared with other ethnic groups [17]. In Greenland, the earliest mention of psoriasis stems from a book from 1940 based on observations done over 30 years by a doctor. Here, a girl in 1912 was described clinically as having psoriasis. Furthermore, an epidemiological study from 1980 found a low incidence of chronic diseases, including psoriasis, in the Upernavik district in northern Greenland in the years 1950-1974 [18].

The objective of a recent study was to estimate the age- and gender-specific prevalence of psoriasis in Nuuk. Sofia Hedvig Christina Botvid, Carsten Sauer Mikkelsen et al conducted the study [19]. Furthermore, we aimed to explore the common risk factors and co-morbidities for patients with psoriasis compared to an age- and gender-matched control group. The study was designed as a cross-sectional case-control study based on national high-quality data from medical records and population registers in Nuuk, from January 1, 2021, to January 1, 2022.

RESULTS

During the study period of 12 months, 175 patients (0.9%) were diagnosed with psoriasis in Nuuk, of which 79 (45%) were females and 96 (55%) were males. The prevalence of patients diagnosed with psoriasis in the adult population aged 20 years old or more in Nuuk was 1.1%. No overall gender-specific difference in prevalence was observed.

Chronic diseases including diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive lung disease were observed more frequently among patients with diagnosed psoriasis (28.6%) in Nuuk compared to controls (20.9%) (p < 0.05).

We found a low prevalence of patients with psoriasis in Nuuk.

We speculate that the prevalence found in this study is underestimated.

A prevalence of 1.1% is considered a low prevalence, as the overall global prevalence of psoriasis is 1.9% [20].

For psoriasis patients in Greenland, there is a need for individual/personalized treatment since every patient has his/her own psoriasis phenotype and every patient has his/her own profile of co-morbidities. Disease activity can fluctuate and vary over time.

Individualizing treatment is needed and a special focus on psoriasis in visible locations like the face, psoriasis of hands, nail psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, inverse psoriasis, and genital psoriasis. Doctors need to focus treatment plans on complaints: like bothering pruritus, severity, pain, and consider gender aspects.

When you live with one autoimmune disease, there is an increased risk of developing other autoimmune diseases. Patients can be associated with different specialist departments, and this can have major consequences for the patient, treatment, and society. Psoriasis patients may feel overlooked in their treatment course, and a reorganization of the treatment may be necessary. We need to optimize the treatment across the different specialties based on an interdisciplinary treatment principle and with an individual approach to the patients, where the psoriasis patient and his diagnoses control the treatment course.

Psoriasis is a chronic disease with a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life. At the moment multiple treatment options are available. It is of utmost importance to provide every patient with the most appropriate therapy, holistic approach, and focus on personalized goals. Personalized treatment and dosage. In severe cases we need to consider precision medicine for the inuits in Greenland.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) in Inuit populations from Greenland

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic debilitating suppurative skin disease clinically manifested by abscesses, fistulas, and scaring with the predominant involvement of the intertriginous region. It is a painful and itchy disease with an unpleasant odour. It is not surprising that HS is a devastating condition leading to a significantly decreased quality of life and increased level of stigmatization. Secondary psychiatric comorbidities, like depression and anxiety, are common. Moreover, a high level of self-destructiveness is observed in this group of subjects. HS is 3 times more common in women and often begins after puberty.

The prevalence of HS is not well known. The group of experts proposed the Worldwide project – The Global Hidradenitis Suppurativa Atlas (GHiSA). Greenland was the first region to join the project. Sofia Hedvig Christina Botvid and Gregor Jemec and their research group used a well-developed methodology that demonstrated that 3.2% of the population suffers from HS lesions [21]. This prevalence was found to be extremely high as in the previous European Guideline on HS the global prevalence of HS was provisionally estimated at the level of 1%.

The important issue is the delay in HS diagnosis. The international study showed that this delay is more than 7 years and visits to about 4 doctors are required to put the correct diagnosis. This delay may result in disease progression and the late introduction of necessary therapy. Therefore, it is of great importance to educate GPs on HS, especially in the early stages of the disease.

The treatment of HS depends on the disease severity. There is a place for conservative treatment as well as for different surgical procedures. Severe cases of HS, also in Greenland, may be managed with the first biological agent registered in HS – adalimumab. However, long-term (10-12 weeks) systemic antibiotic therapy (tetracyclines or combined clindamycin and rifampicin treatment) seems to be a standard for moderate to severe HS.

Hand Eczema in Inuits in Greenland

Hand eczema is a very common dermatological condition worldwide with a particularly rising prevalence post-COVID pandemic. There are multiple factors involved in developing hand dermatitis from atopic constitution to irritancy and allergy. Data on the prevalence and number of cases of hand dermatitis in Greenland are lacking given the relative lack of epidemiological studies and data due to the geographic isolation and occupational and research challenges on the island. Nevertheless, the practitioners in Greenland have all been dealing frequently with hand dermatitis in various clinical presentations and degrees of severity.

Given the multiple factors that Greenland faces from cold weather to intense manual handling (fishing, manual work, etc) hand dermatitis is a frequently encountered problem. One of the main challenges in the treatment of hand dermatitis in Greenland is the general lack of patient adherence and commitment to treatment, which is an essential part of the management. Frequent use of emollients and the avoidance of soaps and the use of soap substitutes are long-term commitments in patients suffering from hand dermatitis. The eczema school established by Dr Lone Storgaard Hove will likely change this in the future given its emphasis on patients’ education which again is an important component of the treatment. The current treatment ladder which in addition to the aforementioned hand care measures starts with potent to very potent topical corticosteroids and systemic therapy as a second-line option. Currently, systemic alitretinoin (a retinoid) is licensed and available in Greenland for severe hand dermatitis unresponsive to topical therapy. It is envisaged that by enhancing awareness of hand dermatitis and emphasizing the importance of regular hand care and timely adherence to treatment in the acute stages to prevent chronicity that all of these measures will lead to a favourable outlook on hand dermatitis in Greenland.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases among Inuits

Venereal diseases in Greenland are very common, especially among teenagers. The incidence of gonorrhea and chlamydia has been slightly decreasing since the record years 2015 and 2017 respectively but is still very high with an incidence of 19.2 and 55.4 per person respectively. 1,000 inhabitants in 2018 [22]. For comparison, corresponding figures for gonorrhea and chlamydia in Denmark in 2018 are respectively 0.58 and 11.5 per 1,000 inhabitants [23]. In both Denmark and Greenland, the majority of those infected with chlamydia are young people under 25 years of age. During the past ten years, the number of reported syphilis cases in Greenland has increased significantly from no reports in 2010 to 118 reports in 2019.

Most reports are registered in larger cities on the west coast: Nuuk, Sisimiut and Ilulissat and in Tasiilaq on the east coast [23]. Another worrying observation is that the number of registered HIV-infected people in 2018 was nine, while the number of new HIV-infected people in Greenland has otherwise been five to six in the period 2015-2017 [23] and that the age of the new HIV-infected people is lower than what has been seen before. Since there are very few registered patients, it is however uncertain whether this is an actual development of the disease incidence.

A multi-pronged approach is suggested to be effective in order to reach as many of the sexually active persons in different age groups, social and cultural levels as possible. Rink et al. and Homøe et al. also suggest that education may be effective in reducing STI incidences [24,25] and should be considered included in a multi-pronged approach.

CONCLUSION

The Greenlanders call their own country Inuit Nunaat or Kalaallit Nunaat, meaning Land of the People or Land of the Greenlanders, respectively (Fig. 6). The Greenlandic people are warm, open-minded people. When healthcare personnel who have worked in Greenland are asked to name their greatest experiences, they often rank the meeting of the friendly and welcoming locals the highest. Unfortunately, it is now difficult to recruit doctors and especially certified Dermatologists. Greenland has many challenges in their health care system. Hopefully the future will improve the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of dermatological diseases in Greenland.

We think it is very importantant to include a holistic approach and ensure adherence.

Ending Quotation

I would like to end this paper with some relevant words, in my opinion:

“When you want to succeed in leading a person to a certain place, you must, first of all, take care to find him where he is and start there. This is the Secret of all Helping Arts.

Anyone who can’t do that is delusional when he thinks he can help someone else.

In order to be able to help someone else truly, I must be able to understand more than he does – but, of course, first and foremost, understand what he understands. When I don’t, my more-understanding doesn’t help him at all. If I still want to make my more-understanding valid, then it is because I am vain or proud, so instead of benefiting him, I want to be admired by him. But all true help begins with humiliation.”

Søren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855) was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

REFERENCES

1. Wu JSA, Florian MC, Rodrigues DA, Tomimori. Skin diseases in indigenous population:retrospective epidemiological study at Xingu Indigenous Park (XIP) and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:1414-20.

2. Taylor SC. Skin of color:biology, structure, function, and implications for dermatologic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 Suppl Understanding):S41-62.

3. Lorentzen AK, Penninga L. Frostbite –A case series from arctic Greenland. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29:392–400.

4. Penninga, L., Lorentzen, A. K., Serup, J., &amp;Mikkelsen, C. S. (2019). Teledermatology in Arctic Greenland. Forum for Nordic Dermato-Venereology, 24(3), 95-97. https://www.medicaljournals.se/forum/articles/24/3/95- 97.pdf

5. Penninga L, Lohrentzen AK, Mikkelsen CS. Kawasaki disease:Two episodes of recurrent disease in a Greenlandic Inuit Boy. Forum Nord Derm Ven. 2019;24:25-7.

6. Schultz Larsen F, Svensson A, Diepgen TL, From E. The occurrence of atopic dermatitis in Greenland. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(2):140-3. doi:

7. Andersson AM, Kaiser H, Skov L, Koch A, Thyssen JP. Prevalence and risk factors for atopic dermatitis in Greenlandic children. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023 Mar 22;48(4):352-360.

8. Tamsmark TH, Koch A, Melbye M, Mølbak K. Incidence and predictors of atopic dermatitis in an open birth cohort in Sisimiut, Greenland. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:982-8.

9. Laughter MR, Maymone MBC, Mashayekhi S, Arents BWM, Karimkhani C, Langan SM et al. The global burden of atopic dermatitis:lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;184(2):304-309. doi:10.1111/bjd.19580. Epub 2020 Nov 29.

10. Andersson AM, Kaiser H, Skov L, Koch A, Thyssen JP. Prevalence and risk factors for atopic dermatitis in Greenlandic children. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023 Mar 22;48(4):352-360

11. Aagaard T. Patient involvement in healthcare professional practice –a question about knowledge. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76:1.

12. Patient empowerment–who empowers whom?Lancet. 2012 May 5;379(9827):1677. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60699-0. Erratum in:Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9842):650.

13. Mikkelsen CS, Jensen JN, Penninga L. Severe atopic dermatitis in arctic Greenland:The importance of patient empowerment. Best Practise, 2021:April.

14. Davis DMR, Eichenfield LF, Frazer-Green L, Paller AS, Silverberg JI, Sidbury R. American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines:Awareness of comorbidities associated with atopic dermatitis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 Jun;86(6):1335-1336.e18.

15. Harvald B. Genetic epidemiology of Greenland. Clin Genet. 1989 Nov;36(5):364-7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb03214.x. PMID:2689006

16. Kromann N. Green Epidemiological studies in the Upernavik district, Greenland:incidence of some chronic diseases 1950–1974. Acta Med Scand. 1980;208:401-6.

17. Farber EM, Nall ML. The natural history of psoriasis in 5,600 patients. Dermatologica. 1974;148(1):1-18. doi:10.1159/000251595. PMID:4831963.

18. Highlights from the first Dermatology Conference in Greenland Mikkelsen CS, Szepietowski JC, Hove LS, Korneliussen M, Firas Ai-Niami, Bjerring P Best Practise July

19. Botvid SHC, Storgaard Hove L, Backe MB, Skovgaard N, Pedersen ML, Sauer Mikkelsen C. Low prevalence of patients diagnosed with psoriasis in Nuuk:a call for increased awareness of chronic skin disease in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2022 Dec;81(1)

20. Kimmel GW, Lebwohl M. Psoriasis:Overview and Diagnosis. Evidence-Based Psoriasis. 2018 Jul 1:1–16. doi:

21. Botvid SHC, Storgaard Hove L, Bouazzi D, Kjærsgaard Andersen R, Francis Thomsen S, Saunte DM, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis Suppurativa Prevalence in Nuuk, Greenland:Physician Validation of a Hidradenitis Suppurativa Questionnaire in a Greenlandic Setting. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023 Jan 10;103:adv00847.

22. Landslægens rapport om seksuelt overførte sygdomme. 2018. https://nun.gl/nyheder/2019/05/seksuelt-overfoerte-sygdomme-i-groenland-i-2018?sc_lang=da

23. SSI. https://www.ssi.dk/sygdomme-beredskab-og-forskning/sygdomsovervaagning/g/gonorre-opgoerelse-over-sygdomsforekomst-2018 https://www.ssi.dk/sygdomme-beredskab-og-forskning/sygdomsovervaagning/k/klamydia—opgoerelse-over-sygdomsforekomst-2018

24. Rink E, Montgomery-Andersen R, Anastario M. The effectiveness of an education intervention to prevent chlamydia infection among Greenlandic youth. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26:98–106.

25. Homøe AS, Knudsen AK, Nielsen SB, Grynnerup AG. Sexual and reproductive health in Greenland:evaluation of implementing sexual peer-to-peer education in Greenland (the SexInuk project). Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015 Oct 28;74:27941.

Notes

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (contact@odermatol.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1202-462X http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1202-462X http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0564-6014 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0564-6014 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3031-1390 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3031-1390 |

Comments are closed.