Red patches on the upper limb

Hanna Cisoń 1, Wojciech Baran1, Leszek Szenborn2, Zdzisław Wożniak3, Rafał Białynicki-Birula1

1, Wojciech Baran1, Leszek Szenborn2, Zdzisław Wożniak3, Rafał Białynicki-Birula1

1Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland, 2Department of Paediatrics and Infectious Diseases, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland, 3Department of General and Experimental Pathology, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2024. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

A 5-year-old girl was admitted to the dermatological ward. Upon conducting a physical examination, the presence of whitish linear area of skin induration with marginal hyperpigmentation was observed on the left upper limb. In the upper part few erosions covered with crusts were seen. Lesions were neither painful nor itchy (Fig. 1).

According to the patient’s mother, the initial cutaneous changes manifested at the age of 2, initially presenting as disseminated red macules on the on the left upper limb (Fig. 2). Girl was consulted by children infectious disease specialist (injections site reaction after vaccination was suspected), haematologist (leukaemia cutis was suspected) and dermatologist without clear conclusion. Biopsy was done at the age of 3, but the final result was lymphocytic infiltration in the dermis, without indication of disease. Within the time macules subsequently transformed into the whitish indurated plaques.

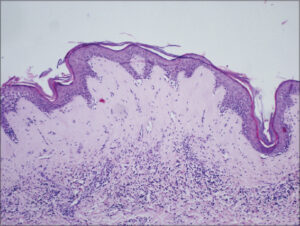

The current biopsy revealed epidermal thinning accompanied by hydropic degeneration in the basal cell layer. Wide band zone of hyalinization and edema in the upper dermis. Telangiectasia and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate below the hyalinised area (Fig. 3).

What is your diagnosis? See next page for answer.

-

a. Jessner lymphocytic infiltration of the skin.

-

b. Primary cutaneous cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma.

-

c. Lichen sclerosus.

-

d. Skin reaction due to and aluminium hypersensitivity induced by childhood vaccines.

-

e. Lymphomatoid papulosis [1].

Extragenital lichen sclerosus (eLS)

The histopathological analysis reveals epidermal thinning accompanied by orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. The basal cell layer exhibits hydropic degeneration. In the papillary dermis, there’s evidence of hyalinization and edema, leading to a hypocellular zone, alongside a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. The diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus was established and systemic treatment was started. In June methotrexate was initiated as a weekly treatment regimen at a dosage of 7.5 mg orally. In September, during follow-up visit no progression of the disease was observed. Significant softening of the skin lesions and no new erosions were found.

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic immunologically mediated dermatological condition characterised by its predominant involvement of the genital skin. The precise etiology and pathogenesis of LS remain elusive [1]. The prevalence of pediatric LS is estimated to range from 0.04% to 0.06%, with a female-to-male ratio of 1:1.7 [2]. The predominant localization of LS is within the genital area, accounting for 94.6% to 99.6% of cases, while extragenital manifestations are observed in 0.4% to 2.8% of patients [3]. However, eLS is relatively infrequent in children, comprising only 5% to 9% of instances [4]. Concurrent involvement of both genital and extragenital sites occurs in approximately 2.9% of cases [5]. A systematic review identified that the average age of LS onset in females was 6.5 years, while in males was 8.6 years. The review also indicated that the mean diagnostic delay for LS in females was 18 months, whereas in males it was 12.5 months [3]. Extragenital lichen sclerosus (eLS) affects anatomical regions including the neck, shoulders, upper trunk, thighs, and oral cavity [5]. ELS presents clinically as asymptomatic or mildly pruritic polygonal confluent papules, exhibiting a characteristic ivory coloration. Notably, eLS is characterised by the presence of comedo-like plugs or evenly distributed depressions aligned with the orifices of cutaneous appendages on the plaque surface. Progressive resolution of these depressions and plaques occurs over time, leaving behind smooth porcelain-white plaques [6]. Occasionally, telangiectasias and blisters may also manifest in eLS, giving rise to erosions that progressively evolve into characteristic white plaques [7]. Furthermore, the Koebner phenomenon is frequently observed in the context of eLS [1]. Histological examination is not required for the diagnosis of LS in adults and children, as the diagnosis is primarily made based on clinical evaluation. However, histopathological analysis may be utilised in cases where there is diagnostic ambiguity, atypical clinical presentations or suspicion of malignancy [8]. In addition, the use of photographic documentation is recommended for monitoring the efficacy of therapy or the progression of the disease in LS patients [9]. The differential diagnosis of eLS is influenced by the size and stage of lesion morphology. In the early stages, eLS exhibits clinical similarities to discoid lupus erythematosus and morphea. Late-stage eLS with hypopigmentation requires differentiation from vitiligo, hypopigmented granuloma fungoides, and atrophic lichen planus. When considering the differential diagnosis of bullous eLS, one should consider bullous lichen planus, autoimmune blistering diseases, bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, and bullous reactions to insect bites [10].

REFERENCES

1. Kirtschig G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:337-43.

2. Kyriakis KP, Emmanuelides S, Terzoudi S, Palamaras I, Damoulaki E, Evangelou G. Gender and age prevalence distributions of morphea en plaque and anogenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:825-26.

3. Balakirski G, Grothaus J, Altengarten J, Ott H. Paediatric lichen sclerosus:a systematic review of 4516 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:231-3.

4. Moreno M. Torrelo A. Mediero I. Zambrano A. Liquen escleroso y atrófico extragenital en ninos. Actas Dermo-Sif. 2000;91:385-9.

5. Matela AM, Hagström J, Ruokonen H. Lichen sclerosus of the oral mucosa:clinical and histopathological findings. Review of the literature and a case report. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76:364-73.

6. Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-418.

7. Burshtein A, Burshtein J, Rekhtman S. Extragenital lichen sclerosus:a comprehensive review of clinical features and treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:339-46.

8. Lewis FM, Tatnall FM, Velangi SS, Bunker CB, Kumar A, Brackenbury F, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus, 2018. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:839-53.

9. Yeon J, Oakley A, Olsson A, Drummond C, Veysey E, Marshman G, et al. Vulval lichen sclerosus:an Australasian management consensus. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:292–9.

10. Arif T, Fatima R, Sami M. Extragenital lichen sclerosus:A comprehensive review. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:452-62.

Notes

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3901-8876 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3901-8876 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6574-8229 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6574-8229 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2603-4220 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2603-4220 |

Comments are closed.