Chronic dermatoses and quality of life: A prospective study on 127 cases at the National Hospital of Niamey, Niger

Maïmouna Mamadou Ouédraogo1, Laouali Salissou 1, Nessiné Nina Korsaga/Somé2, Mamane Sani Idi Laouali1, Hyacinthe Kafando2, Yaya Ouédraogo2, Sareye Ousmane1, Moussa Doulla1, Marcelin Bonkoungou2, Patrice Tapsoba2, Amina Nongtondo2, Fatou Barro2, Pascal Niamba2, Adama Traoré2

1, Nessiné Nina Korsaga/Somé2, Mamane Sani Idi Laouali1, Hyacinthe Kafando2, Yaya Ouédraogo2, Sareye Ousmane1, Moussa Doulla1, Marcelin Bonkoungou2, Patrice Tapsoba2, Amina Nongtondo2, Fatou Barro2, Pascal Niamba2, Adama Traoré2

1Department of Dermatology Venereology, National Hospital of Niamey, Niger, 2Department of Dermatology Venereology, CHU YO Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2023. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Chronic dermatoses are frequent, particularly in sub-Sahelian countries. Most are not life-threatening, yet often have a major impact on the psychological state of the patient and their social relationships, daily activities, and quality of life.

Materials and Methods: For this, we conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study on patients aged fifteen or older with chronic dermatoses, followed at the Department of Dermatology and Venereology of the National Hospital of Niamey from January 1 to June 30, 2017 (for a period of six months).

Results: There were a total of 127 patients. We employed the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) to measure the quality of life of the patients. The aim of our study was to improve the quality of life of patients suffering from chronic dermatoses by the use of the DLQI score.

Conclusion: Chronic dermatoses are frequent in our context. They have an impact on the quality of life of the patients, as evidenced by our study.

Key words: Chronic dermatoses, Quality of life, DLQI score, Niamey, Niger

INTRODUCTION

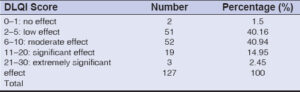

Chronic dermatoses are frequent, particularly in sub-Sahelian countries. Most are not life-threatening yet often have a major impact on the psychological state of the patient and their social relationships, daily activities, and quality of life. The aim of our study was to identify the impact of chronic dermatoses on the quality of life of patients aged fifteen and older at the Department of Dermatology Venerology of the National Hospital of Niamey, Niger. Thus, we employed the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) to measure the quality of life of the patients. It is based on ten questions rated from 0 to 3 relating to pruritus, general discomfort, interference with clothing, hobbies, sport, sexuality, and work. The DLQI score is obtained by summing the scores assigned to each question. It varies from 0 (best quality of life) to 30 (most impaired quality of life) [1–3].

RESULTS

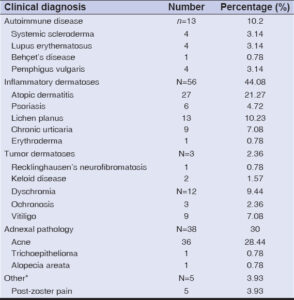

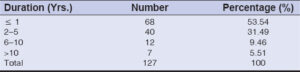

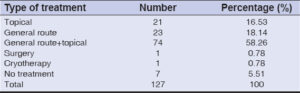

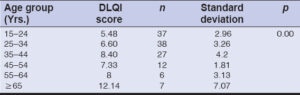

During the study, 127 patients had chronic dermatoses out of a total of 504 patients consulted (25.19%). The average age was 33.38 years, and the age groups of 15–24 years and 25–34 years accounted for 59.08%. Females constituted 57%, giving a male-to-female ratio of 0.76. Living in the urban environment was noted in 88.18%, and 37.79% of the patients had reached high school education. Civil servants accounted for 23.62%. The socioeconomic level was average in 67.71% (Table 1). Inflammatory dermatoses predominated in 44.08%, and acne was the most frequent pathology (28.44%) (Table 2). The average duration of the disease was 3.22 years, and in 53.54% of the cases, the evolution was shorter than one year (Table 3). Systemic treatment associated with topical application was performed in 58.26% (Table 4). The average DLQI score was 7.08, reflecting a moderate deterioration in quality of life in 40.94% of the cases (Table 5). This alteration was moderate in both sexes equally. There was no statistically significant link between sex and quality of life (p = 0.39). Quality of life was more impaired from the age of 65 years, with an average DLQI of 12.14. There was a statistically significant link between patient age and quality of life (p = 0.00) (Table 6). However, while looking for the relationship between age and the DLQI score according to sex, we noted that quality of life was impaired in females after the age of 55 years (p = 0.01) and in males after the age of 65 years (p = 0.00). Quality of life was more impaired with a statistically significant link among farmers (p = 0.006), patients with no schooling (p = 0.014), those from rural areas (p = 0.00), those of low socio-economic level (p = 0.003), patients with autoimmune dermatoses (systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus, pemphigus vulgaris) (p = 0.00), those whose disease duration exceeding ten years (p = 0.00), and those performing a systemic treatment associated with topical application (p = 0.00).

DISCUSSION

Chronic dermatoses are frequent and their impact on quality of life (QOL) has not yet been studied in Niger, Beyond that, we did not find similar studies through our documentary review. In developing countries, epidemiological data collected on dermatological diseases comes mainly from the files of specialized center and do not necessarily reflect the real prevalence in the community, whereas dermatological problems are among the most frequent reasons for consultation in primary care, around 30% of patients in black Africa [4]. In Niger, the sociocultural context, the symbolic meaning of the disease and the religious belief mean that there is a certain fatality, which means that patients complain little. Over 90% of the population is Muslim [5]. Nevertheless, we found a statistically significant link between the sociodemographic, clinical characteristics, and quality of life of our patients. Advanced age, low level of education, precariousness, professions that expose to environmental factors, late consultation, non-compliance with treatment, and cultural influences, particularly in rural areas, are all often associated factors that alter the quality of life of patients suffering from chronic dermatoses. In our Sahel–Saharan context, most of the population lives in rural areas, with a low level of education and precarious financial means. The poorest are also the most likely to be affected by certain types of dermatoses due to higher levels of risky behavior (harmful cultural practices, unhealthy living conditions, psychosocial stress, recourse to traditional healers, self-medication) and highly limited access to quality care. In addition, they are more exposed to environmental factors (sun, wind, torrential rains), chemicals (fertilizers, herbicides), and allergens (pollen), likely to trigger or aggravate certain dermatoses. These patients are most often seen by the specialist at an advanced stage of their pathology causing complications and serious psychological and socioeconomic repercussions (disability, impoverishment, aggravation of already existing poverty, marital conflict and divorce). On the other hand, the clinical manifestations observed during autoimmune dermatoses may be disabling. This is the case for long-term scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and pemphigus vulgaris. A meta-analysis concluded that people with systemic sclerosis are part of a 15% segment of the population with the worst quality of life in terms of health [6]. Terrab, in Morocco, reported that pemphigus caused a significant alteration in health-related QOL [7]. Several studies reported that the QOL of patients with SLE is reduced in all areas assessed and that SLE has a great impact on QOL [8–11]. In our study, acne was the most frequent pathology, yet it slightly affected the patients’ quality of life (average DLQI: 4.69). Acne affects the quality of life of patients regardless of age and sex, yet to different degrees. Ouédraogo et al. [12] found that there was an alteration in the QOL of acne-prone pupils in Ouagadougou and that this alteration was significant for 36.78%, average for 37.51%, and slight for 25.71%. The domains of QOL affected by acne vary according to the sociocultural context: the symbolic meaning of the disease and cultural beliefs [13,14]. In Africa, acne is readily considered a banal temporary disease, even normal; it does not appear likely to alter the quality of life, although its impact on the quality of life of patients has been well documented in several countries in Europe, America, and Asia, in particular on self-esteem and mood in adolescents [15]. The chronicity of these dermatoses and the complexity of the treatment pose the problem of therapeutic compliance as in other chronic diseases (fatigue of the patient, false impression by the patient of the mastery of the treatment). The longer the duration of follow-up, the greater is the risk of poor compliance [16,17]. These last factors are often the cause of complications, recurrences, and impaired quality of life, hence the importance of good therapeutic education.

CONCLUSION

Chronic dermatoses are frequent in our context. They have an impact on the quality of life of patients, as evidenced by our study. The factors influencing this alteration are multiple and often concomitant. A periodic assessment of quality of life is desirable in order to improve their management. The latter must be global, sometimes requiring the cooperation of the dermatologist and psychiatrist.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Finlay AY. Quality of life measurement in dermatology:A practical guide. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:305-14.

2. Khoudri L, Lamchahab FZ, Hassam B. Translation and transcultural adaptation and validation of the Arabic version for Morocco of the Dermatology Life Quality Index. J Epidemiol Pub Health. 2009;57(S):3-59.

3. Kurwa H, Finlay AY. Dermatology in patient admission greatly improves life quality. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:575-8.

4. Pitche P, Tchangaï-Walla K. Dermatology in Black Africa what prospects for the 21st century?Dermatol News. 2000;19:44-7.

5. National Institute of Statistics of Niger. Demography of Niger. [accessed December 7, 2017] available from URL:http:www.//fr.m.wikipedia.org.

6. Hudson M. Quality of life in scleroderma. Autonomous Bulletin. 2009:8.

7. Terrab Z, Lachdar H. Quality of life and pemphigus. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:321-8.

8. Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB and the Committee on prognosis studies in SLE. Derivation of the SLEDAI:A disease activity index for lupus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;3:630-40.

9. Doward LC, Mckenna SP, Whalley D, Tennant A. The development of the SLE-QoL:A quality of life instrument specific to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:196-200.

10. Freire E, Bruscato A, Ciconelli R. Quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus patients in northeastern Brazil:Is health-related quality of life a predictor of survival for these patients?Acta Rheumatol Port. 2009;34:207-11.

11. Wang C, Mayo NE, Fortin PR. The relationship between health related quality of life and disease activity and damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:525-32.

12. Ouédraogo NA, Tapsoba GP, Ouédraogo MS, Soutongo SS, TraoréF, Korsaga NN, et al. Acne and quality of live among pupils in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) IJIAS. 2017;20:187-94.

13. Chuah SY, Goh CL. The impact of post-acne scars on the quality of life among young adults in Singapore. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:153-8.

14. Durai PCT, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in south India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:33.

15. Kouotou EA, Adegbidi H, Belembe RB. Acne in Cameroon:Quality of life and psychiatric comorbidities. Annal Dermatol Venereol. 2016;143:601-6.

16. Amraoui N, Gallouj S, Berraho MA, Najjari C, Mernissi FZ. Therapeutic compliance in chronic dermatoses:About 200 cases. Pan African Medical Journal 2015;22:116.

17. Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Manuel JC, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212-6.

Notes

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 |

Comments are closed.