Paradoxical cutaneous manifestations induced by TNF inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Rhita Alaou i1, Sofia Alami2, Nawal Lagdali1, Maryeme Kadiri1, Camélia Berhili1, Fatima-Zahra Chabib1, Mohamed Borahma1, Imane Benelbarhdadi1, Fatima-Zahra Ajana1

i1, Sofia Alami2, Nawal Lagdali1, Maryeme Kadiri1, Camélia Berhili1, Fatima-Zahra Chabib1, Mohamed Borahma1, Imane Benelbarhdadi1, Fatima-Zahra Ajana1

1Department of Hepato-Gastroenterology “Medicine C”, Ibn Sina University Hospital Center, Mohammed V University Rabat, Morocco, 2Department of Dermatology, Ibn Sina University Hospital Center, Mohammed V University Rabat, Morocco

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2023. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Anti-TNF drugs have revolutionized the management of numerous inflammatory diseases, yet they may produce paradoxical effects.

Materials and Methods: A descriptive study was conducted on patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on anti-TNF therapy who had developed paradoxical psoriasis.

Results: Out of a total of 218 patients followed for IBD on TNF inhibitors, five presented with paradoxical psoriasis. In four patients, a specific treatment for psoriasis was associated with anti-TNF treatment. In one patient, a swap to ustekinumab was decided. Good progress was noted in four patients. In one, there was no improvement of the psoriasis on methotrexate, which was switched to another anti-TNF agent.

Conclusion: In our experience, TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis is relatively rare (prevalence of 2.3%). The choice of treatment is reached by assessing the benefit-risk balance.

Key words: Paradoxical cutaneous manifestations; TNF inhibitors; Cutaneous manifestations; Inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Anti-TNF drugs are among the therapeutic tools that have revolutionized the management of numerous inflammatory diseases, including chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis. However, these treatments may produce paradoxical effects and induce the very disease they were designed to treat, as in the case of psoriasis. Thus, when faced with TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis in a patient with IBD, there is a dilemma. The question is whether the treatment should be continued or stopped or whether the therapeutic class should be changed. Herein, we report five cases of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis in patients followed for IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective descriptive study was conducted on 218 patients with chronic IBD on anti-TNF therapy who developed paradoxical psoriasis when on treatment. The assessment of the severity of skin involvement took into account the extent of the psoriatic rash, its location, and its impact on the patient’s quality of life.

Ethics Statement

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

RESULTS

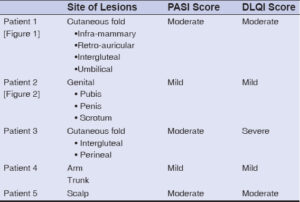

Out of a total of 218 patients followed for IBD on TNF inhibitors, five presented with paradoxical psoriasis, giving a prevalence of 2.3%. Among them were three females and two males, with an average age of 43 years. Our patients had no personal or family history of psoriasis. All five patients had Crohn’s disease, among whom two had ano-perineal manifestations. Three patients were on adalimumab and two on infliximab. The mean time to the onset of paradoxical psoriasis was nine months from the beginning of the treatment. In four cases, the psoriasis lesions appeared during the clinical and endoscopic remission of IBD and, in only one case, the patient was in a clinical relapse. These were two cases of inverse psoriasis (Figs. 1a – 1c), one of genital psoriasis (Figs. 2a and 2b), one of plaque psoriasis, and one of scalp psoriasis. Skin involvement was moderate in three cases and mild in two (Table 1). Histological confirmation was required in one patient.

|

Table 1: A summary of the location and severity of psoriasis. |

In four patients, TNF-inhibitor therapy was maintained and combined with psoriasis-specific treatment (dermocorticoids in two cases, methotrexate in one, and keratolytic cream in one). In the only patient with moderate psoriasis who was in a Crohn’s disease relapse, TNF-inhibitor therapy was suspended and a swap to ustekinumab was decided by a bi-disciplinary concertation. Good progress was noted in four patients. In one, there was no improvement of the psoriasis on methotrexate, hence the need for a switch to another anti-TNF agent, with good progression thereafter.

DISCUSSION

Anti-TNF-a drugs have been clearly shown to be effective in the treatment of numerous inflammatory diseases, including chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and psoriasis. Paradoxically, these treatments may induce and/or worsen psoriatic skin lesions. The prevalence of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis in IBD is estimated to be between 1.6% and 2.7% [1,2], which is consistent with our experience (2.3%).

In the current literature, infliximab is the most frequently reported TNF-a inhibitor to induce psoriatic eruptions, followed by etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab [3]. Despite this, the incidence rate of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis remains the same for all anti-TNF agents [2]. In our experience, adalimumab was responsible for psoriasis in three cases and infliximab in two.

The different risk factors identified as predisposing to TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis are smoking, the female sex, and a genetic predisposition to psoriasis [2]. In two studies, patients with IBD and TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis had no personal or family history of psoriasis [1,2], which was also the case in our experience.

Clinically, patients may present with different forms of psoriasis, including plaque psoriasis, palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, and inverse psoriasis [4]. The most common phenotype of psoriasis was palmoplantar pustulosis [1]. In our experience, there were two cases of inverse psoriasis, one case of genital psoriasis, one of plaque psoriasis, and one of scalp psoriasis.

The median time from the beginning of treatment to the appearance of skin lesions was twelve months (maintenance period). In our experience, the time from the initiation of treatment to the appearance of skin lesions was nine months on average.

Induced psoriasis lesions most often appeared during the remission of IBD, as shown in a study on fourteen pediatric patients [5]. In our experience, psoriatic lesions appeared during the remission of IBD in four cases.

Regarding treatment, there is no standard approach to the management of TNF-induced psoriasis, making the treatment of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis a challenge. A review of the literature was presented on TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis with a proposed treatment algorithm [6], which takes into account both the severity of the rash and the characteristics of the underlying disease. The decision to continue, suspend, or replace anti-TNF therapy should be carefully discussed with the patient, taking into account the severity of the rash, the needs of the underlying disease, and the availability of other treatment options. It should be noted that the severity of the rash should be defined taking into account the extent of the psoriatic rash as well as its impact on the patient’s quality of life (e.g., the involvement of the palms, soles, face, and genitals, and the psychological impact), as recommended by the National Psoriasis Foundation [7].

For patients with mild psoriatic disease and stable underlying disease, a “continuous treatment” strategy is employed, in which anti-TNF therapy is continued in combination with conventional psoriasis-specific therapy (topical steroids, UV therapy, methotrexate (MTX), cyclosporine and acitretin) [6]. Cyclosporine should be used in the short term and with great caution, especially in patients with severe IBD, as it may be lethal in combination with anti-TNF drugs [8,9]. A 2016 study revealed that 45% of patients on MTX achieved a 75% reduction in the psoriasis severity index score after 12–16 weeks [10]. Furthermore, the largest study to assess the efficacy of MTX in patients with IBD showed 59.9% and 40% efficacy for CD and UC, respectively, with rates comparable to smaller studies on this issue [11]. In our experience, the only patient who received MTX in combination with an anti-TNF agent had no improvement of their psoriatic lesions.

This “continuous treatment” strategy resulted in a complete resolution in 26% to 41% of cases and a partial response in 25% to 57.4% [3,12,13], making it a highly attractive treatment option, especially since the discontinuation of TNF inhibitors may worsen gastrointestinal symptomatology.

However, for patients with mild psoriatic disease and underlying IBD poorly controlled by TNF inhibitors or in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and IBD stabilized on TNF inhibitors, it has been proposed to switch to another anti-TNF agent while maintaining psoriasis-specific treatment. However, the success rate of this approach is limited as complete resolution has only been observed in 5% to 36.7% of cases, with a partial response in 18.4% of cases [3,12–14]. More than half of patients may experience a recurrence of skin lesions after the reintroduction of another TNF inhibitor or the same TNF inhibitor [2,15]. In our experience, the only patient who had a switch of their anti-TNF agent had an improvement of their psoriatic lesions without recurrence.

In the refractory cases of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis and patients with moderate to severe rash whose underlying a disease is not well controlled, it is suggested that a change of the drug class in combination with a topical or systemic psoriasis therapy should be undertaken. This may increase the chance of the resolution of paradoxical psoriasis and the underlying IBD. Indeed, it has been reported that, in approx. 64.3% of cases, patients who discontinue TNF inhibitors and switch to non-anti-TNF treatments see the resolution of their psoriatic lesions [14]. In our experience, the only patient who was swapped to ustekinumab was in the process of improving their psoriatic lesions.

The change in the therapeutic class would be toward ustekinumab (anti-IL12/23 agent), which is indicated both for the treatment of active and anti-TNF refractory IBD and for moderate to severe psoriasis. Dermatologically, ustekinumab is an effective and safe treatment for psoriasis [16]. Some studies have shown that ustekinumab resolved skin lesions in more than 75% of cases [17], and one study reported that resolution was complete in 75% of cases. Yet, even with this seemingly revolutionary molecule, some cases of paradoxical psoriasis have been described [18–20].

It is also recommended that immunosuppressive agents, such as 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine, should be reconsidered in some cases, when compared to novel biological therapies [6].

CONCLUSION

TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis is a real dilemma for the gastroenterologist and dermatologist because of a lack of a standard approach to its management. The benefit/risk balance must be assessed in order to avoid deleterious effects on either the gastrointestinal tract or the skin. The choice of treatment depends on the severity of the underlying pathology and the dermatological lesions and should be made on a case-by-case basis and by a bi-disciplinary consultation. The difficulty lies in the fact that all drug classes may cause paradoxical psoriasis.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Afzali A, Wheat CL, Hu JK, Olerud JE, Lee SD. The association of psoriasiform rash with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in inflammatory bowel disease:A single academic center case series. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:480-8.

2. Guerra I, Pérez-Jeldres T, Iborra M, Algaba A, Monfort D, Calvet X, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and management of psoriasis induced by anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease:A nationwide cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:894-901.

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, Huynh M, Wehner M, Matro R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-a inhibitor-induced psoriasis:Systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-41.

4. Joyau C, Veyrac G, Dixneuf V, Jolliet P. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy and increased risk of de novo psoriasis:Is it really a paradoxical side effect?Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:700-6.

5. Eickstaedt JB, Killpack L, Tung J, Davis D, Hand JL, Tollefson MM. Psoriasis and psoriasiform eruptions in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:253-60.

6. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF Inhibitor-induced psoriasis:Proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80.

7. Pariser DM, Bagel J, Gelfand JM, Korman NJ, Ritchlin CT, Strober BE, et al. National Psoriasis Foundation clinical consensus on disease severity. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:239-42.

8. Maser EA, Deconda D, Lichtiger S, Ullman T, Present DH, Kornbluth A. Cyclosporine and infliximab as rescue therapy for each other in patients with steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2008;6:1112-6.

9. Leblanc S, Allez M, Seksik P, FlouriéB, Peeters H, Dupas JL, et al. Successive treatment with cyclosporine and infliximab in steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:771-7.

10. Gladman DD. Should methotrexate remain the first-line drug for psoriasis?The Lancet. 2017;389:482-3.

11. Rouiller-Braunschweig C, Fournier N, Pittet V, Dudler J, Michetti P. Efficacy, safety and mucosal healing of methotrexate in a large longitudinal cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Digestion. 2017;96:220-7.

12. Collamer AN, Battafarano DF. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy:Clinical features and possible immunopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:233-40.

13. Collamer AN, Guerrero KT, Henning JS, Battafarano DF. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy:A literature review and potential mechanisms of action. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:996-1001.

14. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy:A review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatol Treat. 2009;20:100-8.

15. Iborra M, Beltrán B, Bastida G, Aguas M, Nos P. Infliximab and adalimumab-induced psoriasis in Crohn’s disease:A paradoxical side effect. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:157-61.

16. Kimball AB, Papp KA, Wasfi Y, Chan D, Bissonnette R, Sofen H, et al. Long-term efficacy of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated for up to 5 years in the PHOENIX 1 study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2013;27:1535-45.

17. Tillack C, Ehmann LM, Friedrich M, Laubender RP, Papay P, Vogelsang H, et al. Anti-TNF antibody-induced psoriasiform skin lesions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease are characterised by interferon-g-expressing Th1 cells and IL-17A/IL-22-expressing Th17 cells and respond to anti-IL-12/IL-23 antibody treatment. Gut. 2014;63:567-77.

18. Lee HY, Woo CH, Haw S. Paradoxical flare of psoriasis after ustekinumab therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:794-5.

19. Deheb Z, Schmutz JL, Bursztejn AC, Poreaux C, Barbaud A. Àpropos d’un cas :réaction paradoxale sous ustékinumab. Ann Dermatol Vénéréologie. 2014;141:S434.

20. Benzaquen M, Flachaire B, Rouby F, Berbis P, Guis S. Paradoxical pustular psoriasis induced by ustekinumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease-associated spondyloarthropathy. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:1297-9.

Notes

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8364-5717 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8364-5717 |

Comments are closed.