Vitiligo and quality of life: On fifty cases in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Nomtondo Amina Ouédraogo 1,2, Muriel Sidnoma Ouédraogo1,2, Gilbert Patrice Tapsoba1,2, Fagnima Traoré3, Patricia Félicité Tamalgo1, Léopold Ilboudo4, Nadia Kaboret4, Joelle Zabsonré/ Tiendrébeogo2,5, Marcellin Bonkoungou5, Salamata Lallogo6, Séraphine Zeba7, Nessiné Nina Korsaga2,7, Pascal Niamba1,2,8, Adama Traoré1,2, Fatou Barro2,9

1,2, Muriel Sidnoma Ouédraogo1,2, Gilbert Patrice Tapsoba1,2, Fagnima Traoré3, Patricia Félicité Tamalgo1, Léopold Ilboudo4, Nadia Kaboret4, Joelle Zabsonré/ Tiendrébeogo2,5, Marcellin Bonkoungou5, Salamata Lallogo6, Séraphine Zeba7, Nessiné Nina Korsaga2,7, Pascal Niamba1,2,8, Adama Traoré1,2, Fatou Barro2,9

1Department of Dermatology-Venereology of Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital (YO UH), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2Health Science Training and Research Unit, Joseph Ki-Zerbo University, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 3Department of Dermatology, Regional University Hospital of Ouahigouya, Burkina Faso, 4Raoul Follereau Center of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 5Rheumatology Department of Bogodogo University Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 6Dermatology Unit of Saint Camille Hospital in Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 7Dermatology Unit of Boulmiougou District Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 8Dermatology Unit of Camp General Sangoulé Lamizana Medical Center, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 9Department of Dermatology of Tingandogo University Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Corresponding author: Nomtondo Amina Ouédraogo, MD

Submission: 02.12.2021; Acceptance: 22.02.2022

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20223.6

Cite this article: Ouédraogo NA, Ouédraogo MS, Tapsoba GP, Traoré F, Tamalgo PF, Ilboudo L, Kaboret N, Zabsonré/Tiendrébeogo J, Bonkoungou M, Lallogo S, Zeba S, Korsaga NN, Niamba P, Traoré A, Barro F. Vitiligo and quality of life: On fi fty cases in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(3):268-272.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Healthy skin with integrity is essential for maintaining one’s physical, mental, and social wellbeing. Vitiligo, a chronic autoimmune dermatosis characterized by asymptomatic, achromic macules, affects the integrity of the skin.

Methodology: This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted from March to June 2019 in six public hospitals in the city of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The patients included in the study were followed in the dermatology departments of these structures for vitiligo, aged at least eighteen years and consenting. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the vitiligo-specific health-related quality of life scale (VitiQoL) were employed to measure QoL (quality of life).

Results: A total of fifty patients agreed to participate in the study. The mean age was 40.56 years, ranging from 18 to 79 years. There were as many females as males (25), and 23 married patients out of the fifty. The majority of the patients (43/50) resided in urban areas. Twenty-six patients had at least secondary education and eighteen patients worked in the informal sector. The average duration of vitiligo progression was 10.56 years, ranging from three months to 49 years. The evolution of vitiligo was stationary for 17/50 patients. The lesions were mainly located on the head and neck. The average body surface area (BSA) affected was 12.04%, ranging from 1% to 82%. The treatment was mainly local and general corticosteroid therapy. The evaluation of the patients’ quality of life (QoL) by the DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index) yielded a mean score of 5.44/30. Vitiligo had a small effect on the QoL of eighteen patients and a moderate effect on sixteen patients. VitiQoL assessment yielded a mean total score of 32.32/96 and stigma had the highest score of 18.04/36. The patients’ QoL was influenced by age and body surface area affected by vitiligo. Restriction of participation in activities and changes in the patient’s behavior were significantly correlated with the duration of vitiligo progression, followed by stigma, which was related to vitiligo progression.

Conclusion: The alteration of the QoL of the patients with vitiligo was low to moderate. This alteration was related to the stigmatization by one’s environment.

Key words: Vitiligo; Quality of Life; Stigma

INTRODUCTION

Healthy skin with integrity is essential for maintaining one’s physical, mental, and social wellbeing [1,2]. Vitiligo, a chronic autoimmune dermatosis characterized by asymptomatic, achromic macules, affects the integrity of the skin [3,4]. It affects 0.5% to 2% of the world’s population, regardless of race and sex [5]. It is highly conspicuous, especially on black skin, and may produce significant psychological and socioeconomic repercussions on the life of the affected individual [6–8], hence the interest of our study, with the objective to evaluate the impact of the disease on the quality of life of patients suffering from vitiligo followed in the dermatology and venereology departments of the public health structures of the city of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study from March 1 to June 28, 2019, in six public hospitals of the city of Ouagadougou: Yalgado OUEDRAOGO University Hospital, Tingandogo University Hospital, Bogodogo University Hospital, Saint Camille Hospital of Ouagadougou, Raoul Follereau Center RFC, and Medical Center of General Sangoulé Lamizana Camp. The patients included in the study were followed in the dermatology departments of these structures for vitiligo, aged at least eighteen years and consenting. The Wallace rule of nines was employed to calculate the body surface area (BSA). The vitiligo-specific health-related quality of life scale (VitiQoL) was employed to measure quality of life [9–11]. It was the Brazilian Portuguese version (VitiQoL-PB) translated into French to which we added a seventeenth question: “Do you feel rejected by some people when you are in a group?” The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was also used [12–14]. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for the comparison of two variables and the ANOVA test for the comparison of more than two variables. p (probability) was significant if below 0.05. The relationship between the different variables was searched by the Pearson correlation coefficient and the probability was significant if p 0.01. The study respected the rules of ethics by the informed consent of the patients and confidentiality in the processing and analysis of data.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Aspects

In all departments involved in the study, out of 229 cases of vitiligo identified in four years, fifty patients agreed to participate in the study. The majority of the patients (33/50) were followed at the Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital, RFC, and the Boulmiougou District Hospital.

The mean age of the patients was 40.56 years, ranging from 18 to 79 years. There were as many females as males (25), and 23 married patients out of the fifty. The majority (43/50) resided in urban areas. Twenty-six patients had at least secondary education and eighteen patients worked in the informal sector. The average monthly income was €170, ranging from €30 to €2286.

The average duration of vitiligo progression was 10.56 years, ranging from three months to 49 years. The evolution of vitiligo was stationary for seventeen out of the fifty patients. The lesions were mainly located on the head and neck. The average body surface area (BSA) affected was 12.04%, ranging from 1% to 82%. The treatment was mainly local and general corticosteroid therapy.

Quality of Life

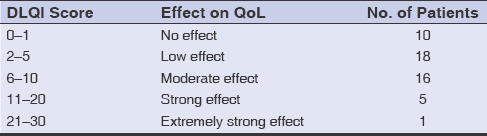

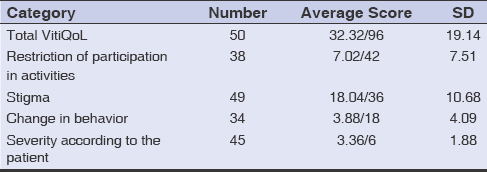

The evaluation of the patients’ QoL by the DLQI yielded a mean score of 5.44/30. Vitiligo had a small effect on QoL for eighteen patients and a moderate effect for sixteen (Table 1). VitiQoL assessment yielded a mean total score of 32.32/96 and stigma showed the highest score of 18.04/36 (Table 2).

|

Table 1: Assessment of quality of life by the DLQI |

|

Table 2: Mean VitiQoL scores in vitiligo |

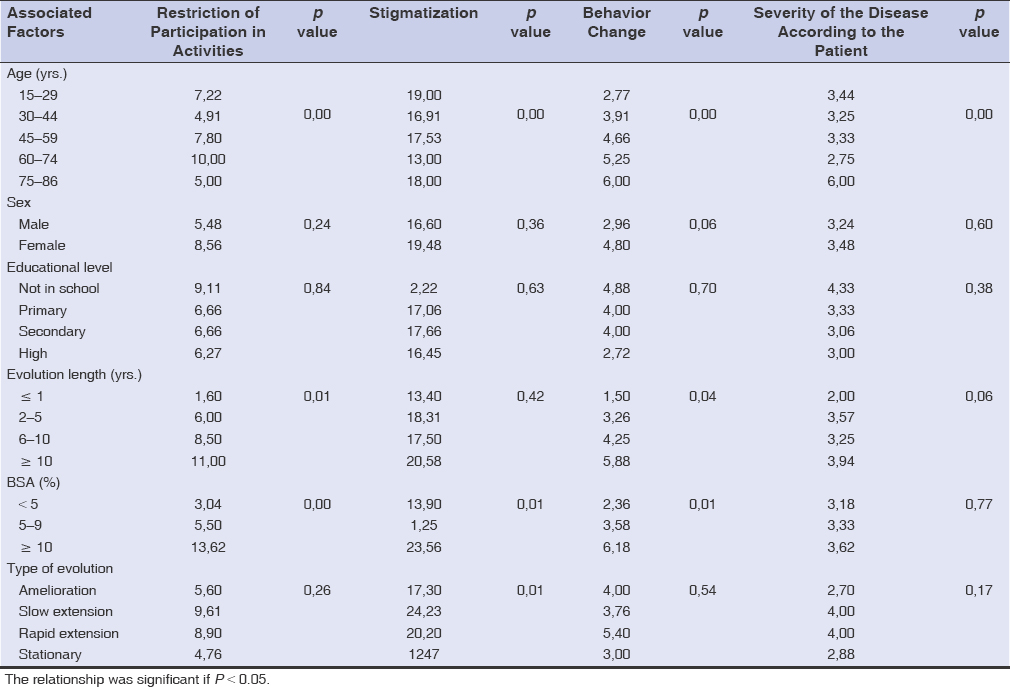

The patients’ QoL was influenced by age and body surface area affected by vitiligo. Restriction of participation in activities and changes in the patient’s behavior were significantly correlated with the duration of vitiligo progression, followed by stigma, which was related to vitiligo progression (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Relationship between the QoL of vitiligo patients and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics |

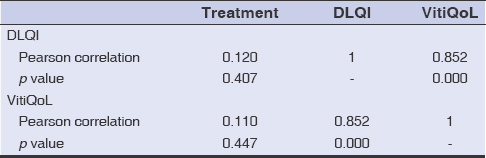

Cross-tabulating the questions related to treatment for the DLQI and VitiQoL scores revealed that there was no impact of treatment on the QoL of patients with vitiligo (Table 4). There was also a strong and significant correlation between the two quality of life scales DLQI and VitiQoL (r = 0.852; p = 0.000). This means that the two tools reflected the same perspective on quality of life assessment.

|

Table 4: Correlation between the DLQI, VitiQoL, and treatment |

Correlation between QoL and professional relationships: Among the fifty patients with vitiligo, twelve were gainfully employed. The correlation between QoL and decreased productivity was significant (r = 0.704; p = 0.011).

DISCUSSION

Our sample included as many females as males and the average age was 40.56 years. Morales-Sanchez in Mexico in 2017 found, with a larger sample size, 103 females vs. 47 males with vitiligo, and then a mean age of 38 years [6]. In our study, the most represented age range was 18 to 29 years for patients with vitiligo, reflecting the importance of vitiligo in the young population [15,16].

Those with at least high school education were 26/50 vitiligo patients. Boza in Brazil in 2017 also found patients with high school education (61/93) [16].

For our patients, the mean duration of the evolution of vitiligo was 10.56 years. Boza found a similar duration (13.9 years) [16]. Kiprono in Tanzania in 2013 found a shorter disease course (8.34 years) [17].

The average body surface area (BSA) affected was 12.04% and treatment was mainly corticosteroid therapy. This is due to the inaccessibility of certain molecules in our country, notably tacrolimus, which produces good results on vitiligo [18].

Quality of Life

Impaired QoL was not influenced by sex (p = 0.18) of the vitiligo patients according to VitiQoL. However, females were more affected than males with higher scores. Other authors reported the same findings [6,10,16,19].

Stigmatization was the most reported concern with the highest score (18.04), reflecting a significant psychosocial impact on patients, especially young people aged 18 to 29 years and those with extensive lesions (BSA ≥ 10). This was also reported by Boza, who noted a score of 16.75 for stigmatization [16]. Rahimi in Afghanistan also noted that these patients suffered from stigma [19]. This could be explained by the fact that it was at this age that young people began to work and be confronted with professional and family responsibilities. Therefore, they had difficulty accepting their illness. In addition, the feeling of shame was experienced more frequently by young people than by older.

The mean DLQI was 5.44, indicating a low alteration in vitiligo patients’ QoL. This result was comparable to those by Turkish, Mexican, Brazilian, and Tanzanian authors, ranging from 3 to 7.2 [6,13,16,17].

The mean VitiQoL score was 32.32/90, corresponding to a low alteration in the patients’ QoL. This result was comparable to those reported by Iranian (30.5) and Brazilian (37) authors [10,16].

The assessment of QoL by the VitiQoL dimensions yielded mean scores of 7.02, 18.04, 3.88, and 3.36, respectively, for the dimensions: restriction of participation in activities, stigmatization, behavior changes, and severity, according to the patient. We noted, then, that stigma contributed the most to the alteration in the patient’s QoL. Boza made the same finding in their study cited above (14.23; 16.75; 9.15; and 3.6) [12]. Rahimi also mentioned the same [19].

The significant stigmatization of patients by their environment would be linked to the ignorance of the disease, hence the fear of contamination. This stigmatization, as well as the fact that the disease is displayed overtly, is the reason for the change in the patient’s behavior, with the restriction of their participation in social activities. This leads to isolation also mentioned in other skin diseases [20–23].

There was a strong correlation between the DLQI and VitiQoL (r = 0.852; p = 0.000). This means that the two tools reflected the same view on quality of life assessment, a finding also reported by Boza and Morales-Sanchez [6,16].

CONCLUSION

The alteration in the quality of life of our patients with vitiligo was low to moderate. This alteration was related to the stigmatization of the environment. Young people with extensive lesions (BSA ≥ 10) and aged between 15 and 29 years were the most stigmatized.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Pärna E, Aluoja A, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in chronic skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:312-6.

2. Cella D. Quality of life:Concepts and definition. J Pain Symptom Manag 1994;9:186-92.

3. Migayron L, Boniface K, Seneschal J. Vitiligo, from physiopathology to emerging treatments:a review. Dermatol Ther, 2020;;6:1185-98.

4. Halder MR, Chappell JL. Vitiligo update. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. WB Saunders, 2009. 86-92.

5. Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, Pandya AG, Harris JE. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1-13.

6. Morales-Sánchez MA, Vargas-Salinas M, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Olguín-García MG, Jurado-Santa Cruz F. Impact of vitiligo on quality of life. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográf. 2017;108:637-42.

7. Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, Schwartz RA. Vitiligo and depression:A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-18.

8. Amer AAA, Gao XH. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo:An analysis of the dermatology life quality index outcome over the past two decades. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:608-14.

9. Lilly E, Lu PD, Borovicka JH, Victorson D, Kwasny MJ, West DP, et al. Development and validation of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life instrument (VitiQoL). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:11-8.

10. Hedayat K, Karbakhsh M, Ghiasi M, Goodarzi A, Fakour Y, Akbari Z, et al. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo:A cross-sectional study based on Vitiligo Quality of Life index (VitiQoL). Health Quality Life Outcom. 2016;14:86-94.

11. Essa N, Awad S, Nashaat M. Validation of an Egyptian Arabic version of Skindex-16 and quality of life measurement in Egyptian patients with skin disease. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25:243-51.

12. Henseler T, Schmitt-Rau K. A comparison between BSA, PASI, PLASI and SAPASI as measures of disease severity and improvement by therapy in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1019-23.

13. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI):A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-6.

14. Arora CJ, Rafiq M, Shumack S, Gupta M. The efficacy and safety of tacrolimus as mono-and adjunctive therapy for vitiligo:A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:e1-e9.

15. Sof K, Aouali S, Bensalem S, Zizi N, Dikhaye S. Dermatoses in the hospital and their impact on quality of life. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12:462-3.

16. Boza JC, Giongo N, MacHado P, Horn R, Fabbrin A, Cestari T, et al. Quality of Life Impairment in Children and Adults with Vitiligo:A cross-sectional study based on dermatology-specific and disease-specific quality of life instruments. Dermatology. 2017;232:619-25.

17. Kiprono S, Chaula B, Makwaya C, Naafs B, Masenga J. Quality of life of patients with vitiligo attending the Regional Dermatology Training Center in Northern Tanzania. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:191-4.

18. Carlier L. Utilisation hors AMM du tacrolimus dans le traitement du vitiligo. Thèse de doctorat en pharmacie. Universitéde Bordeaux;2015, 105 p.

19. Rahimi BA, Farooqi K, Fazli N. Clinical patterns and associated comorbidities of vitiligo in Kandahar, Afghanistan. A case-control study. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:6-12.

20. Salman A, Kurt E, Topcuoglu V, Demircay Z. Social anxiety and quality of life in vitiligo and acne patients with facial involvement:A cross-sectional controlled study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:305-11.

21. Nguyen CM, Beroukhim K, Danesh MJ, Babikian A, Koo J, Leon A. The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis:A review. Clin Cosm Invest Dermatol. 2016;9:383-92.

22. Ghajarzadeh M, Ghiasi M, Kheirkhah S. Associations between skin diseases and quality of life:A comparison of psoriasis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata. Acta Medica Iranica. 2012;50:511-5.

23. Kawshar T, Rajesh J. Sociodemographic factors and their association to prevalence of skin diseases among adolescents. Our Dermatol Online. 2013;4:281-86.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 |

Comments are closed.