Factors related to response to propranolol treatment for infantile hemangiomas: a cross-sectional study on a Moroccan population

Hanane Bay Bay 1, Mariam Atassi2, Aicha Alaoui1, Samira Elfakir2, Widade Kojmane3, Samir Atmani3, Mostapha Hida3, Fatima Zahra Mernissi1

1, Mariam Atassi2, Aicha Alaoui1, Samira Elfakir2, Widade Kojmane3, Samir Atmani3, Mostapha Hida3, Fatima Zahra Mernissi1

1Dermatology Department of the University Hospital Center Hassan II, Fez, Morocco; 2Laboratory of Epidemiology, Clinical Research and Community Health- Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez, Fez, Morocco; 3Pediatric Department of the University Hospital Center Hassan II, Fez, Morocco

Corresponding author: Prof. Hanane Bay Bay

Submission: 16.02.2020; Acceptance: 20.04.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20203.1

Cite this article: Bay Bay H, Atassi M, Alaoui A, Elfakir S, Kojmane W, Atmani S, Hida M, Mernissi FZ. Factors related to response to propranolol treatment for infantile hemangiomas: a cross-sectional study on a Moroccan population. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(3):224-230

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: There is no consensus on the optimal duration of propranolol treatment in complicated infantile hemangiomas (IHs), and factors related to its response have not yet been addressed, especially as it relates to the northern Moroccan region.

Aim: We analyze the factors of good response of IH to propranolol treatment in a Moroccan population; thus, this study is the first to consider an undeveloped country.

Methods: A descriptive and analytic study was conducted for 9 years in our department. The following parameters were analyzed: epidemiologic, therapeutic, and progressive, as well as the factors responsible for therapeutic response.

Results: Propranolol treatment for 153 cases of IH was completed. With an average age of 7.9 months, a tuberous form was found in 50.3% of the cases, with 58.1% located on the face. Side effects were minor, and response was good to excellent in 95.6% of the cases. In a univariate analysis, children over 12 months and those with mixed hemangioma, as compared with those with a tuberous form, were less likely to exhibit an excellent response (OR = 0.18 with a 95% CI = 0.03–0.68; and OR = 0.80 with a 95% CI = 0.68–0.94). Excellent response was more prevalent in children treated for more than 6 months (47.8% vs. 11.8%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Our study proves the safety and efficacity of propranolol as a treatment of IH. Excellent response was very much correlated with age, clinical form of IH, and the duration of treatment.

Key words: Infantile hemangioma, Propranolol, Factors, Morocco

INTRODUCTION

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are vascular tumors that undergo a proliferative phase followed by stabilization and involution [1]. Approximately 10% of IHs require intervention during the proliferative phase since they can grow dramatically or can often locate on the face, which may lead to functional impairment, cosmetical disfiguration, and complications such as ulceration, bleeding, and infection [1,2]. Oral propranolol (OP) is an effective treatment for complicated IHs [1]. Its dosage, effectiveness, and adverse effects, as well as monitoring of treatment, have been widely described [3–7]. There is no consensus on the optimal duration of propranolol treatment for infantile hemangiomas, and factors related to response to propranolol treatment in infantile hemangiomas have not yet been addressed, especially in the northern Moroccan region [3]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of an oral propranolol solution administered for high-risk IHs in a Moroccan population of the minimum age of 6 months up to the maximum age of 24 months in order to analyze factors related to the response of propranolol treatment.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

A prospective observational study was conducted from September 2008 to September 2017 by the dermatological and pediatric services at Hospital Center University Hassan II, located in Fez, Morocco. Data was collected from 153 patients treated for hemangioma with propranolol. The criteria of inclusion were an age of less than 2, hemangiomas with functional risks, namely, orificial locations, hemangiomas complicated by bleeding or ulceration, and those larger than 25 cm2 in nonrisk locations. The criteria of exclusion were medical contraindication to beta-blockers and hemangiomas smaller than 25 cm2 in nonrisk locations. All patients had been receiving short-stay hospitalization where their clinical data and pretreatment assessments were collected. Propranolol treatment was initiated under 24-hour monitoring at 1 mg/kg/day for 1 week. Then, patients underwent evaluation and the dose was increased to 3 mg/kg/day split into 2 doses. The treatment continued until the growth of hemangiomas stopped. Follow-ups were scheduled for once a month for the first year and once every 3 months for the second year. The following parameters were analyzed: epidemiologic, therapeutic, and progressive, as well as the factors of good and bad therapeutic response. Treatment was stopped at a time determined primarily by the lesion regression rate in the reduction of the size and coloration of hemangiomas. Therapeutic evaluation was based on a score [8] ranging from 0 to 3. A score of 3 was an excellent response, if regression was above 75% without any scars; a score of 2 was a good response, if regression ranged between 50% and 75% with or without scars; a score of 1 was a poor response, if regression ranged between 25% and 50% with or without scars; and a score of 0 was no response, if regression was below 25% or no regression was observed. Informed parental consent was systematically collected.

Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis of variables was conducted. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies, and continuous variables were summarized by means and standard deviations.

A univariate and multivariate analysis classified children according to their treatment response: excellent vs. good. The variable of interest was dichotomic and the event was to have an excellent response. The 4 children who had a poor response to treatment or none were excluded from the analysis. Fisher’s test and simple logistic regression were used to investigate the association between treatment response and each of the following factors: gender, age, the size and number of hemangiomas, the clinical form of the hemangioma, the presence of ulceration, the progression of hemangiomas, the age at the onset of propranolol treatment, and the duration of the treatment. These factors were selected according to medical knowledge and previous findings [9,10]. Age was included in the analysis as a categorical variable (≤12 months and >12 months).

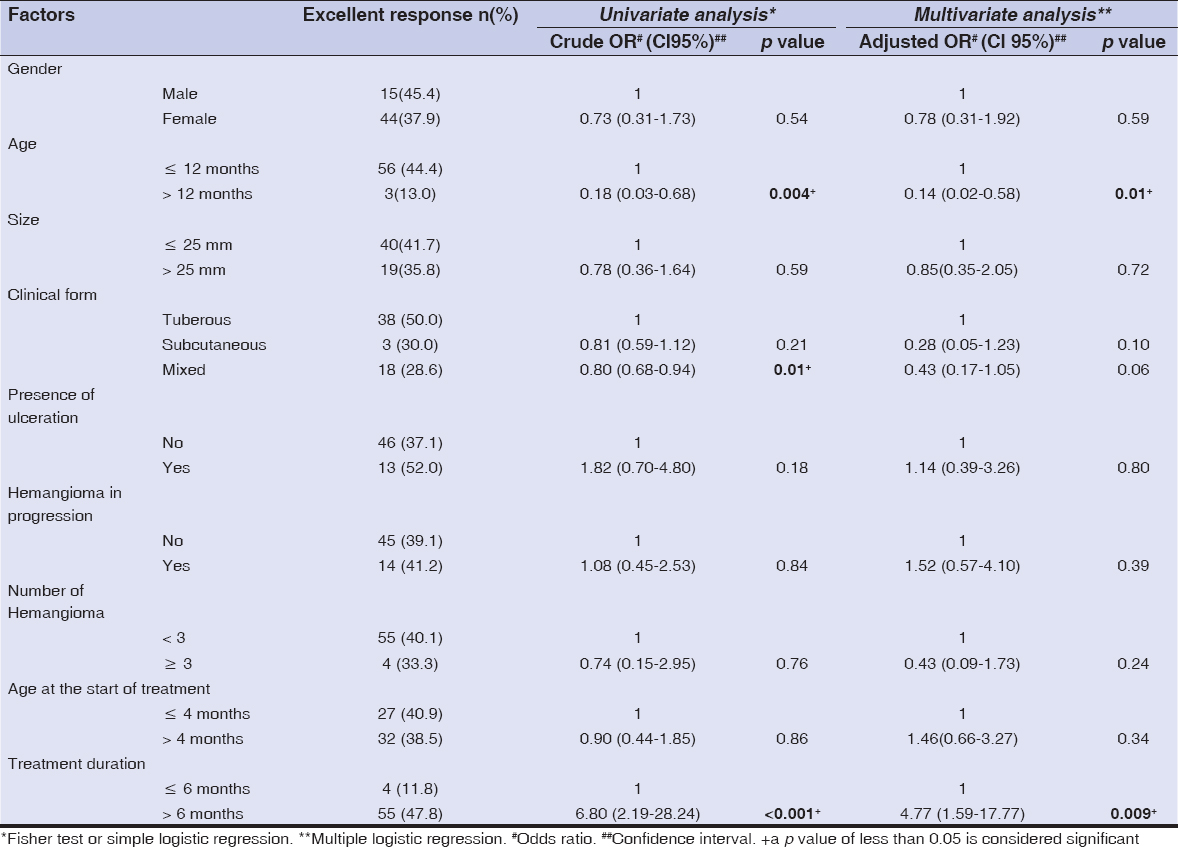

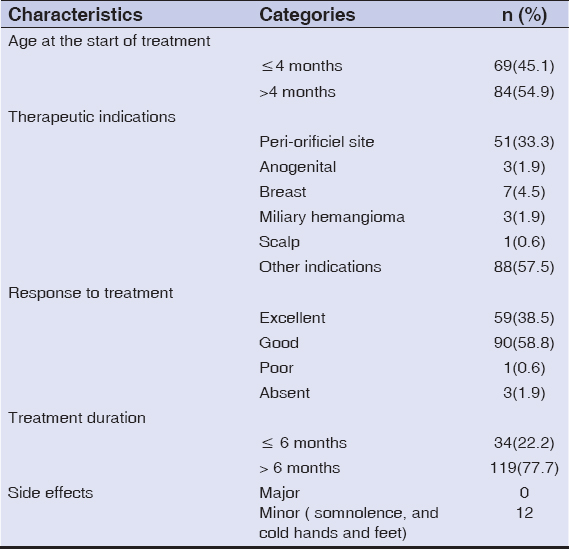

In multiple logistic regression, association with excellent responses was tested after adjusting for potential confounders and factors cited above (Table 1). Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were provided for each variable. All statistical analyses were performed in the software R, version 3.5.1 (R Core Team (2018). R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees at Hospital Center University Hassan II in Fez, Morocco. All subjects were informed of the conditions related to the study and gave their written informed consent.

RESULTS

Clinical and Therapeutic Characteristics

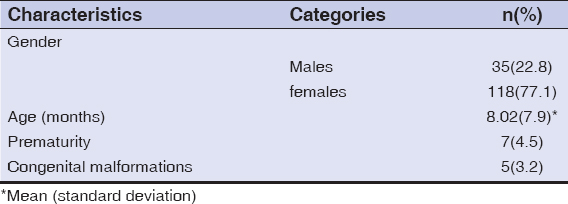

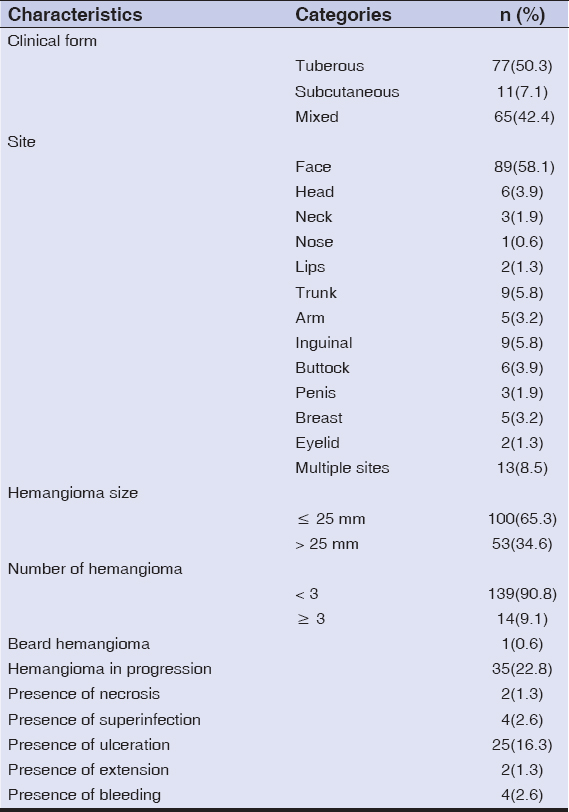

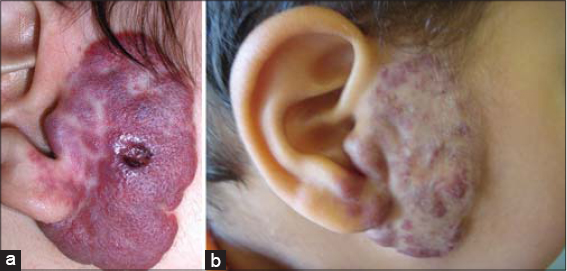

Among the 153 children studied and treated for infantile hemangioma with propranolol, 118 (77.1%) were female, and the average age was 8 months (±7.9). Prematurity was reported in 7 (4.5%) children, and congenital malformations in 5 (3.2%) children (Table 2). The tuberous form was the most common (50%), followed by the mixed form (42.4%). More than half (58.1%) of hemangiomas were located on the face, with 3.9% segmental facial hemangiomas; other locations were mostly those of the trunk (5.8%), inguinal areas (5.8%), and head (3.9%). The size of hemangiomas was less than 25 cm2 in 65.3% of cases, and only 9.1% of the patients had more than 3 hemangiomas. As for the other criteria, 22.8% of hemangiomas were in progression, 16.3% displayed ulcerations, while superinfection was reported in 4 (2.6%) cases. More details are described in Table 3. Propranolol treatment was administered below the age of 4 months for 69 (45.1%) children. A periorificial location was a therapeutic indication in 33.3% of cases. More than two thirds (77.7%) were treated for more than 6 months. The median duration of treatment was 15 months. Response to treatment was good (Fig. 1) to excellent in 95.6% of patients (Fig. 2), poor in one patient (0.6%) (Fig. 3), and no response to treatment was attained in only 3 patients (Fig. 4) (Table 4). No relapses were observed after the end of the treatment.

Factors Related to Excellent Responses to Propranolol Treatment

In a univariate analysis, excellent responses to propranolol treatment were correlated considerably with age, the clinical form of hemangioma, and the duration of treatment. Children of over 12 months and those with mixed forms of hemangioma, unlike those with tuberous forms, had a lesser chance of attaining an excellent response to propranolol treatment (OR = 0.18 with a 95% CI = 0.03–0.68; and OR = 0.80 with 95% CI = 0.68–0.94). Excellent responses were more prevalent among children treated for more than 6 months (47.8% as opposed to 11.8%; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

After adjusting for confounding factors, association with excellent responses, age, and the duration of treatment declined but remained significant (p = 0.01 and p = 0.009, respectively). On the contrary, association with mixed forms disappeared (p = 0.06). The size and number of hemangiomas, the progression of hemangiomas, the presence of ulceration, and the age at the onset of treatment were not significantly associated with treatment response (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 10% of IHs require treatment during the proliferative phase due to local complications, a life-threatening location, cosmetic issues, or functional risks [3–7]. In 2008, Léauté-Labrèze et al. reported an incidental finding that propranolol could control dramatically the growth of IH. Subsequent studies were conducted and demonstrated that the drug was well tolerated and produced excellent results [6,10] The exact mechanism of oral propranolol treatment for IH has not been elucidated [1,3,4]. There are several proposed hypotheses, including vasoconstriction, decreased renin production, inhibition of angiogenesis, and stimulation of apoptosis. The author concluded that increased apoptosis during the second year of life can offset cellular proliferation and may be involved in initiating the regression of hemangiomas [5,11,12].

This study demonstrated that the efficacy of oral propranolol at 3 mg/kg/day for >6 months in IH Moroccan patients gave good or excellent responses even if the age at the onset of treatment was, in some cases, high. Furthermore, the treatment was deemed relatively safe because almost no side effects were observed in younger patients [6,9]. Indeed, the authors concluded that the use of oral propranolol is well tolerated, effective, and safe in the treatment of IH during the postproliferative phase [4,6,7]. According to the literature, the duration of treatment with systemic propranolol ranges from 1 to 16 months [3,11,12]. In our study, the duration of oral propranolol IH treatment introduced after the proliferative phase ranged from 6 to 24 months, with 15 months as a median duration of treatment. Although propranolol is well tolerated and is rarely associated with adverse reactions [1,3], our study, nonetheless, produced minor side effects, such as somnolence and cold hands and feet. As for criteria such as gender, location, and clinical form, numerous publications give similar reports [1,3,11,13]. Propranolol withdrawal produced no relapses. The explanation given is the duration of treatment, which was longer and appropriate for the evolution of IH [14,15]. Factors related to excellent responses to propranolol treatment were age, clinical forms of hemangioma, and the duration of treatment. These factors were demonstrated, in some studies, to be factors of relapse [1,3,4,13]. In fact, it is known that therapeutic responses in tuberous forms are more favorable than in mixed and subcutaneous forms. Introducing treatment during the first year of life is a hugely important factor as it coincides with the proliferative phase [3,4,13]. The fact that this phase varies in length between tuberous forms and subcutaneous forms [16–18] could explain the good response of treatment despite a late introduction of treatment, but with a longer duration, that is, for up to 6 months. In our study, late introduction of treatment is explained, on the one hand, by the delay in specialized consultation and, on the other hand, by the little knowledge of therapeutic opportunities of some clinicians. Additionally, the size, number, and progression of hemangiomas, the presence of ulceration, and the age at the onset of treatment were not significantly associated with treatment response. Indeed, in nearly all publications, it is not the size that influences response, but composition and quantity [16–18]. As for ulceration and hemangioma progression, during the first 3–5 months, superficial IH proliferates rapidly. In most cases (80%), the growth is complete by 5 months of age [1,4,9]. In contrast with superficial lesions, deep IH often lags in growth by approximately 1 month. These lesions proliferate for one additional month on average. Despite these well-defined parameters, IHs are very heterogeneous during the early proliferative phase and the growth characteristics of individual IHs can be difficult to predict. By 9 months of age, lesions begin to regress by 10% annually until in complete or partial subsidence [16–18]. Tumor tissue is replaced by fat and fiber components, and the tumoral skin often loosens or scars. In our study, propranolol was 95.6% effective for IH treatment during the proliferative and postproliferative phases. The first results appeared within hours of initiating treatment, and changes in lesion color and softening were observed [1,17,18]. Such involution was not associated with the location of hemangiomas or the age at the onset of treatment. The majority of authors agree that an acceptable response is expected if treatment is introduced within the first 12 months of life. As recently reported by Chang LC et al., most hemangiomas cease growing after 9 months of age. However, there was a small subgroup of hemangiomas with continued growth after this period [12]. Our study was limited to a Morocco population and, as such, represents research in a previously poorly represented country.

CONCLUSION

Although the exact mechanism causing the beneficial effects of propranolol in the proliferative and postproliferative phases are unclear, a better understanding of the mechanism of propranolol-induced regression of IH may allow for more effective treatment. Moreover, an administration of oral propranolol 3 mg/kg/day is safe and effective for IH during the proliferative and postproliferative phases and should be considered a first-line treatment in Moroccan populations. Factors related to excellent responses to propranolol treatment were associated significantly with the age of ≤12 months, tuberous forms, and the duration of hemangioma treatment. Additionally, the optimal duration of treatment should end no sooner than with the regression of IH, that is, more than 6 months since its introduction. Finally, it has to be noted that Morocco is a country unrepresented in these sorts of studies and that genetic factors may also play a role in these treatment mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to all patients who participated in this study and gave their consent. We would like to thank all volunteer investigators and the medical staff at the department of dermatology, pediatrics, and clinical epidemiology for their enormous help. We would also like to give special thanks to dermatologists Radia Chakiri and Meriem Soughi for their help in the elaboration of this study.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975..

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

2. Vivar KL, Mancini AJ. Infantile hemangiomas:An update on pathogenesis, associations, and management. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2018;19:293-303.

3. Lahrichi A, Hali F, Baline K, Fatoiki FZE, Chiheb S, Khadir K. Effects of propranolol therapy in Moroccan children with infantile hemangioma. Arch Pediatr. 2018;25:449-51.

4. Kaneko T, Sasaki S, Baba N, Koh K, Matsui K, Ohjimi H, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral propranolol for infantile hemangioma in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2017;59:869-77.

5. Xu MN, Zhang M, Xu Y, Wang M, Yuan SM. Individualized treatment for infantile hemangioma. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1876-9.

6. Léaute-Labrèze C, Boccara O, Degrugillier-Chopinet C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Prey S, LebbéG, et al. Safety of oral propranolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma:a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138:pii:e20160353.

7. Babiak-Choroszczak L, Giżewska-Kacprzak K, Dawid G, Gawrych E, Bagłaj M, LebbéG, et al. Safety assessment during initiation and maintenance of propranolol therapy for infantilehemangiomas. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019;28:375-84.

8. Polites SF, Rodrigue BB, Chute C, Hammill A, Dasgupta R. Propranolol versus steroids for the treatment of ulcerated infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e27280.

9. Novoa M, Baselga E, Beltran S, Giraldo L, Shahbaz A, Pardo-Hernandez H, et al. Interventions for infantile haemangiomas of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD006545.

10. Zou Z, Guo L, Mautner V, Smeets R, Kiuwe L, Friedrich RE. Propranolol Specifically suppresses the viability of tumorous schwann cells derived from plexiform neurofibromas in vitro. In Vivo. 2020;34:1031-6.

11. Baselga E, Dembowska-Baginska B, Przewratil P, González-Enseñat MA, Wyrzykowski D, Torrelo A, et al. Efficacy of propranolol between 6 and 12 months of age in high-risk infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2018;142:pii:e20173866.

12. Chang L, Gu Y, Yu Z, Ying H, Qiu Y, Ma G, et al. When to stop propranolol for infantile hemangioma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43292.

13. Wu C, Guo L, Wang L, Li J, Wang C, Song D. Associations between short-term efficacy and clinical characteristics of infantile hemangioma treated by propranolol. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14346.

14. Shehata N, Powell J, Dubois J, Hatami A, Rousseau E, Ondrejchak S, McCuaig C. Late rebound of infantile hemangioma after cessation of oral propranolol. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:587-91.

15. Giachetti A, Garcia-Monaco R, Sojo M, Scacchi MF, Cernadas C, Guerchicoff Lemcke M, et al. Long term treatment with oral propranolol reduces relapses of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:14-20.

16. Tani S, Kunimoto K, Inaba Y, Mikita N, Kaminaka C, Kanazawa N, et al. Change of serum cytokine profiles by propranolol treatment in patients with infantile hemangioma. Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14:89-92

17. Vivas-Colmenares GV,Bernabeu-WJ,Alonso-Arroyo V, Matute de Cardenas JA, Fernandez-PI. Effectiveness of propranolol in the treatment of infantile hemangioma beyond the proliferation phase. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:348.

18. Tian Y, Xu D-P, Tong S, Xi S, Liu Z, Wang X-K. Evaluation of treatment of infantile hemangiomas by oral propranolol in the post-proliferation phase:a case series of 31 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74:1-4.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/000-0003-3455-3810 |

Comments are closed.