Dermatitis herpetiformis: celiac disease of the skin. Report of two cases

Beatriz Di Martino Ortiz1, Hugo Macchi2, Celeste Valiente Rebull3, María Lorena Re Dominguez3, Guadalupe Barboza3

1Dermatology Department, Clinicas Hospital, Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of Ausunción-Paraguay; 2Department of Endoscopy, Clinicas Hospital, Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of Ausunción-Paraguay; 3Clinicas Hospital, Faculty of Medical Sciences, National University of Ausunción-Paraguay

Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Beatriz Di Martino Ortiz, E-mail: beatrizdimartino@gmail.com

Submission: 09.03.2017; Acceptance: 30.06.2017

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20181.13

ABSTRACT

Dermatitis herpetiformis or Duhring-Brocq disease is a chronic, autoimmune, pleomorphic disease, characterized by lesions on extension surfaces, accompanied by intense pruritus, and is usually associated with celiac disease, gluten sensitivity, gluten sensitivity ataxia and some forms of IgA neuropathy. Two cases of dermatitis herpetiformis are presented in female patients and we make a brief review of the literature on the treatment of this pathology.

Key words: Dermatitis herpetiformis; Duhring-Brocq disease; Celiac disease

INTRODUCTION

Dermatitis herpetiformis was first described by Louis Adolphus Duhring in 1884 at the University of Pennsylvania [1–3]. In 1888 Brocq described similar lesions diagnosed as “pruritic polymorphic dermatitis” [4]. It is also known as Duhring-Brocq disease [2–4]. However, the association of celiac disease, gluten-sensitive enteropathy and dermatitis herpetiformis was observed by Mards, Fry and Shuster in the 1960s [4].

It is characterized by the presence of IgA deposits in the dermal papillae [1,5].

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with recurrent episodes where autoantibodies are not directed at any molecules of the dermoepidermal binding complex [3,6].

CLINICAL CASES

Case 1: 22 years old white female, from urban area of Paraguay, student. She presents a 9 months of evolution of raised reddish lesions, some with clear liquid content at the beginning, which then present crusts, accompanied by intense pruritus, initially in arms and legs, then in neck and abdomen. She auto medicate herself with topical clobetasol and moisturizing creams, with improvement of pruritus, that reappears when suspending. Deny relatives with similar pathology.

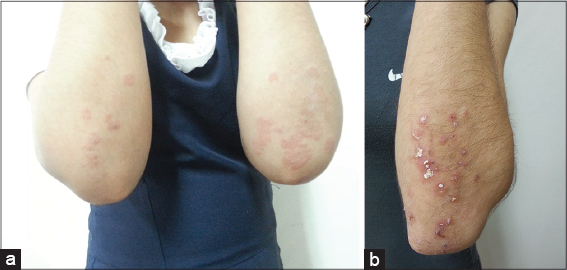

Physical examination shows multiple erythematous plaques and papules, some with blisters of citrus liquid content, others with crusts of 0.4 to 1.5 cm, net limits, regular borders, seated on forearms, buttocks, chest and abdomen (Figs. 1a and 1b).

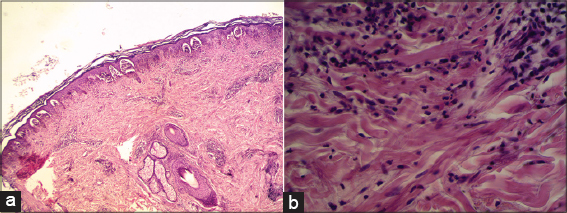

Histopathological examination: histopathological subepidermal vesicles, with micro papillary neutrophil abscesses (Figs. 2a and 2b).

Direct immunofluorescence: granular IgA deposits in dermoepidermal junction.

Laboratories: HIV and VDRL negative.

Endoscopy: scalloping of folds and reduction in the number of folds.

Final diagnosis: Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Evolution: Betamethasone plus fusidic acid, antiallergic, but the patient does not return to the consultation.

Case 2: 8 years old White female, from urban area of Paraguay, student. She presents a picture of 1 year of evolution of raised reddish pruriginous lesions, some with clear liquid content, that break and cover of crusts, that initiate in elbows and extend to knees and buttocks. It is treated several times with Betamethasone with partial improvement. These lesions show irregular outbreaks.

Physical examination: erythematous plaques of 1 to 1.5 cm, net limits, irregular borders, some confluent, that settle on forearms and buttocks (Figs. 3a and 3b).

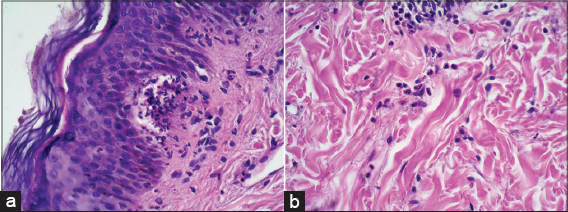

Histopathological examination: histopathological subepidermal vesicles, with micro papillary neutrophil abscesses (Figs. 4a and 4b).

Direct immunofluorescence: granular IgA deposits in dermoepidermal junction.

Laboratories: Anti-transglutaminase antibody IgA positive, anti-gliadin positive IgG antibody.

Endoscopy: scalloping of folds and reduction in the number of folds.

Final diagnosis: Dermatitis Herpetiformis.

Evolution: request consultation with Gastroenterology and gluten-free diet. Betamethasone and anti allergic. Good evolution.

DISCUSSION

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a relatively rare disease. It is observed mainly in men, in a proportion 2:1, predominates in the north of Europe and in Caucasians. The highest incidence is in Ireland, with 1 person affected per 300 inhabitants.

The family incidence is 2.3 to 6.5%, as well as concordance in twins and celiac disease [6].

It is exceptional in children under 3 years of age, and may appear at any age, but the peak incidence is in the third decade [5,6].

In pathogenesis, HLA DQ2 and HLA DQ8 haplotypes are known to be involved, both in dermatitis herpetiformis and in celiac disease [7,8]. 90% of patients are DQ2 positive, and the remaining DQ8 [5,6]. The association with HLA DR3, B8 and A1 explains the association with other autoimmune diseases [9].

The fundamental environmental factor in the development of both pathologies is the exposure to gluten, which causes the formation of autoantibodies against gliadin, which is the protein constituent thereof [6].

At the time of DH diagnosis, celiac disease is asymptomatic or is associated with malabsorption, but 60% is asymptomatic, with 60 to 70% of alterations in the intestinal biopsy [10]. However, there are no skin manifestations in those severe cases of celiac disease [6].

On physical examination, there may be present lesions such as papules, plaques, vesico blisters that develop commonly on extensor surfaces and buttocks, which are very itchy. In addition, excoriations, hyperpigmented scars may be present, because these lesions have periods of remission [1–10].

In children, it is common to find petechial or echimotic lesions in palmoplantar regions, especially at fingertips [6,7].

Mucosal involvement is rare, although IgA is frequently deposited in these regions [7]. Other less common forms are also seen as palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, purupuric lesions with the appearance of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and lesions that mimic prurigo pigmentosum [7,11].

Differential diagnoses arise with atopic dermatitis, scabies, prurigo, papular urticaria, eczema, and blistering lesions such as linear IgA dermatitis and pemphigoid. Other pathologies also to be ruled out are erythema multiforme, urticaria and prurigo in adults [6,11].

The diagnosis is clinical, histopathological, immunological and serological.

Histopathology shows subepidermal vesicles or blisters, with neutrophil abscesses in the dermal papillae, and occasionally eosinophils could be found in the dermal infiltrate, which makes it difficult for the differential diagnosis with the bullous pemphigoid. So the gold standard is the direct immunofluorescence [11].

Direct immunofluorescence shows the deposit of IgA in the basement membrane [11–13].

This deposit currently has 3 patterns [11]:

- A granular pattern that is deposited on the dermal papillae.

- A granular deposit in the basement membrane, and

- A fibrillar IgA deposit in the dermal papillae.

In addition, deposits of perivascular IgA and in the upper dermis, as well as granular IgM or deposits of C3 in the dermoepidermal junction can be found [11].

Serological tests, especially anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and antiendomysium, are sensitive and specific tools for initial detection of gluten-sensitive diseases as well as for dermatitis herpetiformis [13].

Tissue anti-transglutaminase antibodies are elevated in patients with intestinal activity and decreases with the adoption of a gluten free diet [7].

Epidermal anti-transglutaminase (eTG) antibodies are specific antigens of DH, but so far only for research purposes and not for the clinical management of patients [11].

DH is also associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune thyroid diseases, pernicious anemia, gastric atrophy, type 1 diabetes mellitus, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Schogren’s disease, vitiligo and alopecia areata [7].

It is associated with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, T-cell lymphomas associated with enteropathy [6].

In patients with celiac disease/dermatitis herpetiformis, non-specific antibodies must be detected, such as antithyroid peroxidase (in almost 20% of patients), gastric parietal cells (in 10-25% of patients), antinuclear and anti- Ro/SSA. The presence of such antibodies correlates with the autoimmune predisposition of patients with celiac disease/dermatitis herpetiformis [13].

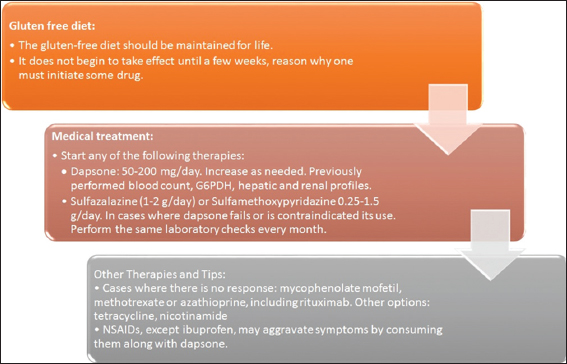

The treatment of DH is based on three pillars, first gluten-free diet, medical treatment that could be with dapsone or sulfapyridine and avoid NSAIDs and iodides [14].

The gluten-free diet must be for life, the same, is effective for the disappearance of skin lesions and digestive manifestations. It also reduces or decreases medication, resulting in the resolution of enteropathy, corrects malabsorption and prevents lymphomas.

Dapsone treatment is effective, it rapidly achieves an improvement in skin lesions and has no effect on gastrointestinal pathology, it has no curative effects [14].

It starts at low doses of 50 mg/day and is progressively increased to 200 mg/day according to the needs of the patient. Plasma G6PDH dosage, blood count, renal and hepatic function should be performed, which are controlled weekly, bi weekly during the first month, monthly during the first three months and then every 3 to 6 months. Methemoglobinemis and hemolysis are dose dependent in many cases [9].

The use of sulfasalazine and sulfamethoxypyridazine are in cases in which treatment with dapsone fails or presents side effects. The suggested dose is 1-2 g/day for sulfazalazine and 0.25-1.5 g/day for sulfamethoxypyridazine. Laboratory controls are performed monthly [14].

Topical corticosteroids are not very effective, but if there is impetiginization, topical antibiotics should be administered [9,14].

In cases in which there is no response to treatment with gluten and dapsone free diet, immunosuppressants such as mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate or azathioprine, including rituximab, may be indicated. Other options could be tetracycline, nicotinamide [14,15].

NSAIDs, other than ibuprofen, have been shown to aggravate symptoms when taken together with dapsone, such as pruritus and rash [15]. The treatment is sumarized in box 1.

CONCLUSION

In summary patients with celiac disease may develop DH by any time. This is most often an indicator of poor adherence to GFD, and a rigorous dietary intervention is necessary. In the majority of cases, DH will be detected without prior celiac disease diagnosis, but the physicians should recognize this phenotype alteration.

REFERENCES

1. Pérez Cortés S, de Peña Ortíz J, Ramos Garibay A, Pérez Maciel CA. Dermatitis herpetiforme. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2007;16:137-42.

2. Miller JL, Zaman SA, Hall R. Editor board:Wells MJ, Nunley JR. Chief Editor:Elston DM. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Updated:Mar 31, 2016. Disponible en:http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1062640.

3. Plotnikova N, Miller JL. Dermatitis herpetiformis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2013;18:1-3.

4. Mendes FBR, Hissa-Elian A, Abreu MAMM, Gonçalves VS. Review:dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:594-9.

5. Herrero-González JE. Guía clínica de diagnóstico y tratamiento de la dermatitis herpetiforme. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:820–6.

6. Iranzo Fernández P. Dermatitis herpetiforme. Patogenia, diagnóstico y tratamiento. Med Cutan Iber Lat Am. 2010;38:5-15.

7. Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, Uyeda H, Ruaro RT, Empinotti JC. Dermatitis herpetiformis:pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-77.

8. Bonciani D, Verdelli A, Bonciolini V, D´Errico A, Antiga E, Fabbri P, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis:from the genetics to the development of skin lesions. Clin Develop Immunol.2012:1-5.

9. Sanjinés L, Martínez M, Magliano J. Dermatitis herpetiforme como carta de presentación de la enfermedad celíaca. Rev Urug Med Interna. 2016;1:5-11.

10. Alonso-Llamazares J, Gibson LE, Rogers RS 3rd. Clinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic features of dermatitis herpetiformis:review of the Mayo Clinic experience. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:910-9.

11. Antiga E, Caproni M. The diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:257–65.

12. Reunala T, Salmi TT, Hervonen K. Dermatitis herpetiformis:patognomonic trasglutaminase IgA deposits in the skin and excellent prognosis on a gluten-free diet. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:917–92.

13. Caproni M, Antiga E, Melani L, Fabbri P. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis. JEADV. 2009;23:633-8.

14. American gastroenterological association medical position statement:Celiac sprue. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1522-5.

15. Da Silva Kotze L. Dermatitis herpetiformis, the celiac disease of the skin. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:231-5.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Comments are closed.