Insect bite like rash induced by bendamustine – A common presentation with an uncommon cause

Shibani Bhatia1, Ananth Pai2, Raghavendra Rao1, Srilatha Parampalli Srinivas3, Varsha M Shetty 1

1

1Department of Dermatology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India, 2Department of Medical Oncology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India, 3Department of Pathology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India

Corresponding author: Dr. Varsha M Shetty

Submission: 23.07.2020; Acceptance: 22.10.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.2020e.152

Cite this article: Bhatia S, Pai A, Rao R, Srinivas SP, Shetty VM. Insect bite like rash induced by bendamustine – A common presentation with an uncommon cause. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(e):e152.1-e152.5.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Bendamustine has become a popular cancer chemotherapeutic agent in the last couple of years. It has replaced some traditional chemotherapy regimens due to its favorable side effect profile. Various cutaneous side effects have been noted following bendamustine usage. These cutaneous eruptions are to known to occur in 15-24% of patients. Benign cutaneous events include lichenoid drug eruptions, flagellate dermatoses and polymorphic papules and plaques in exposed areas. Rarely, severe adverse cutaneous reactions such as Steven Johnson syndrome, drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and toxic epidermal necrolysis have been reported. We report a case of a 48 year-old-female who developed an insect bite like rash after initiation of bendamustine for non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

Key words: Drug rash; Insect-bite like rash; Bendamustine

INTRODUCTION

Bendamustine is a bifunctional chemotherapeutic agent with both alkylating and antimetabolite properties. In 2008, it was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and indolent B-cell non Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL). Chemotherapeutic agents such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone have been previously used for NHL as a part of R-CHOP regimen. However, off late, bendamustine and rituximab in combination has become more popular due to lesser toxicity compared to the earlier R-CHOP regimen. The side effects of bendamustine seem to be well tolerated and include cytopenias, gastrointestinal complaints and fatigue. Bendamustine is known to cause several types of adverse cutaneous reactions ranging from mild forms such as maculopapular rash and polymorphous erythematous papular rash to severe forms such as Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) [1,2]. Herein we report a case of NHL with bendamustine induced insect bite like skin rash.

CASE REPORT

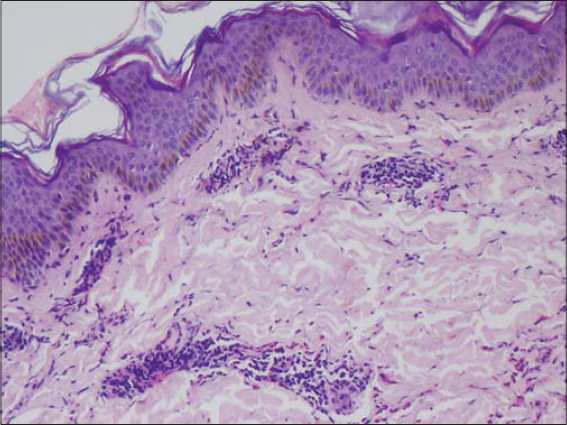

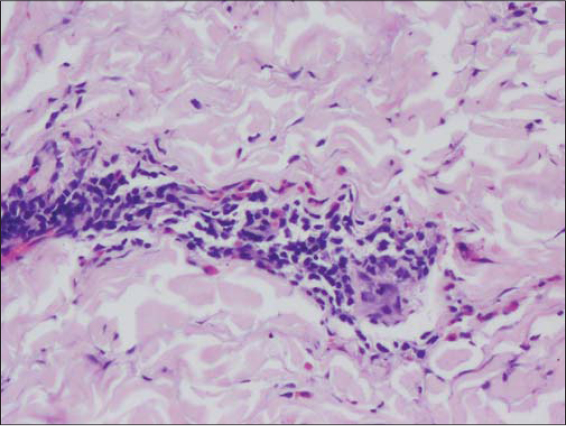

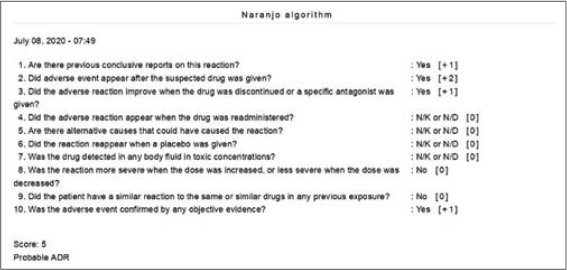

A 48-year-old female patient, who was diagnosed with NHL two months ago developed raised itchy lesions of 2 weeks duration. She said to have developed these lesions 2 weeks after her first cycle of chemotherapy which comprised of a combination of bendamustine and rituximab. She was known to have co-existent hepatitis B infection as her serology had revealed antibodies against Hepatitis B surface antigen. There was no history of insect bite prior to the onset of lesions or atopy. On clinical examination, she had multiple discrete erythematous to hyperpigmented papules and papulo-vesicles which were distributed predominantly on the extensors of bilateral upper and lower limbs (Figs. 1 and 2). A differential diagnosis of papular urticaria and prurigo were considered and she was started on topical steroids and oral anti-histamines empirically. However, the patient visited us again one month later with persistence of the skin lesions associated with severe pruritus. By then she had completed three cycles of bendamustine and rituximab therapy. Her blood investigations revealed leucopenia and peripheral blood eosinophilia. The patient was subjected to skin biopsy which revealed hyperkeratotic epidermis overlying dermis with edema, interstitial and perivascular lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate thus confirming the diagnosis of papular urticaria (Figs. 3 and 4). The biopsy specimen sent from perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination turned out to be negative. In view of the onset of lesions beginning after administration of bendamustine therapy; a diagnosis of bendamustine induced papular urticaria was made. Naranjo algorithm indicated a score of 5 suggesting a probable association of the drug bendamustine resulting in such a rash (Fig. 5). The medical oncologist stopped bendamustine after 3 cycles in view of persistent intolerable itching and started her on R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone) regimen, following which her cutaneous lesions improved as observed during her subsequent follow up visits (Figs. 6 and 7).

Bendamustine is a nitrogen mustard drug which was first synthesized in Jena, the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany), at the institute for microbiology and experimental therapy in the year 1963 [2]. It acts by three mechanisms; which include inhibition of mitotic checkpoints, causing defective DNA repair and by initiation of p53-dependent DNA-damage stress response. It has antimetabolite and alkylating properties which has been used in the treatment of CLL, NHL, Hodgkin’s disease, multiple myeloma and lung cancer. In 2008, it was approved by FDA for CLL and indolent B-cell NHL more so in patients whose disease progressed during or within 6 months of treatment with rituximab or a rituximab-containing regimen [1,2].

Earlier R-CHOP or R-CVP regimen were given for the treatment of lymphomas. However, bendamustine as monotherapy or with rituximab has become more popular in the last decade due to its better safety profile. Bendamustine is observed to be associated with less neutropenia, and fewer episodes of paraesthesia, stomatitis, infection and alopecia [1].

Various cutaneous adverse reactions following bendamustine therapy has been mentioned in several case reports and studies. Cutaneous adverse effects are observed to develop following the very first infusion of bendamustine and generally worsen in severity over the subsequent administrations with the histopathological examination revealing either a diffuse or perivascular eosinophilic infiltration in the dermis. Severe drug reactions such as SJS, TEN and bullous pemphigoid have been reported to occur as early as 1 week after the administration of bendamustine [3]. Other cutaneous manifestations following the administration of bendamustine include palpable purpura, desquamating skin rash, polymorphic pruritic rash, lichenoid drug eruption (LDE) and flagellate dermatitis [2,4–6].

In an original report by Malipatil et al on the use of bendamustine in Indian subcontinent, more than 50% (9/16) of patients were observed to have developed a skin rash. They noticed a polymorphous erythematous papular rash beginning as early as seven to ten days after initiating bendamustine infusion. This rash was observed to predominantly involve the exposed areas of the body very much similar to our patient. Additionally, the authors observed no association of this cutaneous rash with the dose of bendamustine administered, gender of the patient, number of cycles or the infusion protocol followed. However, histopathology in all the nine patients showed chronic inflammatory cells around adnexal structures and thus the authors could not offer any possible explanation to the occurrence of this rash [2]. Unlike the patients reported in the above case series, the histopathological examination of our patient exhibited eosinophilic infiltrate thus raising the possibility of exaggerated response to insect bites.

Similarly, a retrospective study by Nishikori et al, analysed that 11 out of 34 cases (32%) receiving bendamustine therapy, developed a late-onset persistent skin eruption simulating an insect-bite like rash. A higher CD8/CD4 T cell ratio were observed in patients with skin eruptions and they were also seropositive for Hepatitis B core antibody as opposed to rest of the patients who did not develop skin eruptions following bendamustine therapy. This was similar to our patient who was also observed to be harbouring antibodies against Hepatitis B surface antigen. Thus, Nishikori et al proposes such reaction occurring as a result of depletion of CD4+ T cell induced by bendamustine very much similar to that occurring in retropositive patients presenting with pruritic papular eruptions in the setting of severe immunosuppression with CD4+ T cell counts below 200. The simultaneous presence of a latent infection such as hepatitis may as well offer a conducive environment to trigger an exaggerated immune response simulating an immune reconstitution syndrome [6]. A lower leucocyte count (2300cells/μl) was observed in our patient, however analysis of CD4/CD8 ratio was not done due to financial constraints.

Blisters and bullae occurring proximal to injection site has been reported in a patient of mantle cell lymphoma following one cycle of bendamustine-rituximab infusion [7]. Additionally, bullous lesions at the lips and erythematous plaques on the body following one cycle of bendamustine was reported in a patient of follicular lymphoma. On histopathology, interface dermatitis was noted; thus, pointing towards LDE. Bendamustine down regulates CD4+ T cells, thus probably explaining the upregulation of CD8 cells seen in LDE [4].

Eosinophilic dermatoses of haematological malignancy (EDHM) is a distinct disorder characterised by cutaneous lesions simulating arthropod bites which is unrelated to drug intake. A perivascular eosinophilic infiltrate is observed in such patients on histopathology. EDHM though uncommon; must be considered as one of the differentials in patients presenting with papulonodular lesions or blisters in the setting of haematological malignancy [8]. Such lesions may involve both exposed as well as non-exposed areas unlike the classical insect-bite reaction. It is said to occur as a result of altered immune response or hypersensitivity response triggered by malignant cells [9]. However, this was ruled out in our patient as the skin lesions occurred following the administration of bendamustine and disappeared following its stoppage.

Benign adverse cutaneous reactions do not warrant for discontinuation of the drug and the patient may be managed symptomatically with emollients, antihistamines and topical steroids [2,5].

CONCLUSION

Thus, adverse cutaneous drug eruptions continue to pose diagnostic challenge to the clinicians more so in establishing the causality of the culprit drug. In most of the circumstances, the histopathology may not yield a specific diagnosis and the scenario with patients on multiple medications may make it even more confusing for the clinician to identify the causative drug. Bendamustine usage has increased in the last decade owing to its better safety profile and dermatologists must be aware of its cutaneous side effects when such patients are referred from oncology; in order to manage these cases appropriately. There is limited literature in the causation of such insect-bite like rash following bendamustine infusion; however, further studies would result in a better understanding of this entity.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Brugger W, Ghielmini M. Bendamustine in indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma:a practice guide for patient management. Oncologist. 2013;18:954–64.

2. Malipatil B, Ganesan P, Sundersingh S, Sagar TG. Preliminary experience with the use of bendamustine:a peculiar skin rash as the commonest side effect. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2011;4:157-60.

3. Carilli A, Favis G, Sundharkrishnan L, Hajdenberg J. Severe dermatologic reactions with bendamustine:a case series. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7:465–70.

4. Kusano Y, Terui Y, Yokoyama M, Hatake K. Lichenoid drug eruption associated with Bendamustine. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e438.

5. Mahmoud BH, Eide MJ. Bendamustine-induced “flagellate dermatitis“. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:12.

6. Nishikori M, Kitano T, Kobayashi M, Hishizawa M, Kitawaki T, Kondo T, et al. Increased number of peripheral CD8+T cells but not eosinophils is associated with late-onset skin reactions caused by bendamustine. Int J Hematol. 2015;102:53–8.

7. Sahu KK, Sawatkar GU, Jeyaraman P, Prakash G, Varma SC, Malhotra P. Bullae And Blisters:A Rare Case of Bendamustine Skin Toxicity. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32:368–9.

8. Martires K, Callahan S, Terushkin V, Brinster N, Leger M, Soter N. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt8467m0j9.

9. Jayasekera PS, Bakshi A, Al-Sharqi A. Eosinophilic dermatosis of haematological malignancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:692–5.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7837-6388 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7837-6388 |

Comments are closed.