Cutaneous leishmaniasis – A clinico-epidemiological study

Mrinal Gupta1, Shashank Bhargava 2

2

1Treatwell Skin Centre, Jammu, India; 2Department of Dermatology, R. D. Gardi Medical College, Ujjain, India

Corresponding author: Dr. Shashank Bhargava

Submission: 29.06.2020; Acceptance: 14.09.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.2020e.126

Cite this article: Gupta M, Bhargava S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis – A clinico-epidemiological study. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(e):e126.1-e126.3.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

Abstract

Background:: Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a protozoal disease usually caused by Leishmania major and Leishmania ropica, transmitted by bite of a sandfly. It is usually characterized by a single, polymorphous lesion located in an uncovered area.

Methodology:: It was a prospective study carried out over three years, in which the clinico-epidemiological features of patients presenting with CL were assessed.

Results:: A total of 50 patients (male: female – 31:19) were included with a mean age of 38.8 years. Face was the most commonly affected site (42), followed by neck and hands (6 & 2), nodulo-ulcerative was the commonest clinical variant in 46 patients. Skin smears for Leishman–Donovan (LD) bodies were positive in eleven patients while skin biopsy, which was done in four cases, showed the presence of LD bodies in one patient.

Conclusion:: CL is a common protozoal disease in the endemic areas which can cause significant morbidity.

Key words: Leishmanisis; Protozoal infection; Sodium stibogluconate; Endemic

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease caused by Leishmania organism, transmitted by the bite of an infected sandfly (Phlebotomus genera). Depending on the infecting Leishmania species and host immunocompetence, there are cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral forms of the disease [1]. It has been estimated that 350 million people are at risk of leishmaniasis and the disease, in its various forms, affects at least 12 million people worldwide, with 1.5–2 million new cases per year [2]. In India, indigenous cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) are mainly confined to hot, dry North-West Thar Desert of Rajasthan, in certain regions of Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. A typical lesion of the localized form of cutaneous leishmaniasis is a painless papule that enlarges over a period of several days to weeks to form a nodule or plaque, usually on exposed parts of the body such as the face, arms or legs. Atypical clinical variants of the disease have been reported including paronychial, chancriform, annular, palmoplantar, zosteriform, and erysipeloid forms [1,3].

In this study, we examined the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with CL over a period of three years in Jammu region of India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It is a prospective study carried out over a period of three years at our center, in which fifty patients presenting with CL were assessed. A detailed history was taken including the epidemiological data; onset and duration of skin lesion(s), history of associated itching or pain, history of sleeping outdoors, insect bite, house design, and history of a similar illness in the family or neighborhood were recorded on predesigned proformas. After obtaining informed consent, each patient was subjected to general physical, systemic, cutaneous, and mucosal examination. The clinical diagnosis of CL was made using the clinical criteria proposed by Bari and Rahman and this was further confirmed, whenever possible, by the demonstration of Leishman–Donovan (LD) bodies in Leishman-stained slit skin smears and hematoxylin and eosin-stained skin biopsy sections [4]. Culture and polymerase chain reaction could not be done due to the non-availability of these techniques.

RESULTS

A total of 50 patients (male: female – 31:19) were included in the study with the age range of 1–75 years, with a mean age of 38.8 years. The total number of lesions were 62, with eight patients presenting with two or more lesions while the rest had single lesion. Majority of patients belonged to 20-50 years age group (42%, n=21), followed by 50-70 years (30%, n= 15), 1-20 years (24%, n-12) and >70 years (4%, =2). The most common occupational group among males were farmers (n=11), laborers (n=8) and students (n=8) while among the females, housewives (n=15) were the most common occupational group. Majority of respondents in our study group belonged to a rural background (88%, n=44) and were natives of districts of Doda, Kishtwar, Rajouri and Poonch. The duration of skin lesions varied from 1 month to 18 months. Most of our patients lived in mud houses (n = 32), and history of sleeping outdoors was noted in 27 patients. Twelve patients had a history of similar lesions in the family or in the neighborhood.

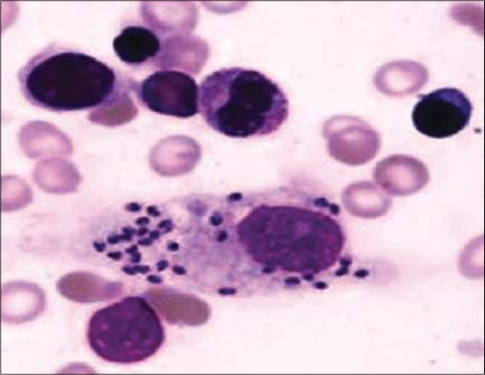

The face was the most commonly affected site (n = 42), followed by neck and hands (6 and 2 respectively), and nodulo-ulcerative was the most common clinical type seen in 46 patients. Over the face, cheeks were involved in 30 cases, nose in 8, and eyelid and lips in 2 patients each (Fig. 1). The most common clinical variant was nodulo-ulcerative (n = 46) followed by erythematous, edematous plaque in four patients. Skin smears for Leishman–Donovan (LD) bodies were positive in eleven patients while the skin biopsy, which was done in four cases, showed the presence of LD bodies in only one case (Fig. 2).

Out of the fifty patients, forty eight were given weekly intralesional sodium stibogluconate (SSG) for durations ranging from 4 to 8 weeks depending on the clinical response while the patients with eyelid lesions were administered daily intramuscular SSG at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 3 weeks.

DISCUSSION

CL is a common parasitic disease with variable clinical manifestations, mostly involving the exposed sites with face, neck, and arms being the most commonly involved [5]. The diverse clinical spectrum of CL results from the complex interaction of a number of factors such as the type and duration of clinical lesions, strain of organism, geographic location, parasitic load, disease reservoir, and host immunocompetence [6]. Lesions caused by CL generally start as a small papule or may occur in a papulo-nodular form which, if untreated, increases in diameter and may ulcerate [7–9]. Diagnosis of CL is often difficult and the patients may be misdiagnosed as impetigo or folliculitis by the practitioners, thereby leading to delayed treatment, which may lead to the spread of disease and scarring. The diagnosis of CL has to be suspected in patients presenting with chronic, nodular, or ulcerated lesions on the face or exposed sites. Atypical leishmaniasis may mimic erysipelas, dermatitis, verruca, herpes zoster, and sporotricosis, we should always keep a suspicious eye for it if we encounter a longstanding and painless lesion [10]. Its presentation may also vary depending on the immune status of the individual, some salient clinical and epidemiological differences were reported among immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients in a study by Jareno et al [11]. The lesions tend to be more ulcerative and angry looking in immunosuppressed cases. It can mimic chancroid and may present with similar morphological lesion over penis [12–14].

In endemic areas, the clinical diagnosis is not difficult. Usually, this is best achieved by performing a smear of the material from the lesion and staining it with Wright or Giemsa stain which may reveal the presence of LD bodies. Demonstration of the parasite in direct smears remains the easiest and the most specific method of diagnosis. The smears are positive in 50%–70% of the cases, depending on the age of lesions; younger lesions being more likely to yield the parasite. Histopathological examination of the lesion may also reveal LD bodies, but the organisms are scarce and difficult to identify in sections stained with H and E stain which may be due to repeated processing of biopsy specimens with dehydrating solutions. Culture of the material in Novy–MacNeal–Nicolle medium or polymerase chain reaction may also be done for the confirmation of the diagnosis [15]. Modern methods for the diagnosis of leishmaniasis include immunofluorescence, use of monoclonal antibodies, DNA probes, polymerase chain reaction, and electron microscopic studies [16,17].

Numerous treatment modalities have been used for the management of CL. The more effective treatment is with pentavalent antimonial compounds or SSG, and the dosage recommended by the World Health Organization is 20 mg/kg/day over 3 weeks [2]. However, intralesional treatment may be considered as a preferential form of treatment for CL among pediatric population so as to avoid the toxicity associated with systemic administration of antimonials [3]. Other modalities of treatment include 20% paromomycin ointment, cryotherapy, liposomal amphotericin B, and oral antifungals [18,19].

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study

REFERENCES

1. Al-Kamel MA. Stigmata in cutaneous leishmaniasis:Historical and new evidence-based concepts. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:81-90.

2. Salissou L, Doulla M, Ouedraogo MM, Brah S, Daou M, Ali D, Adehossi E. [A crushing ulcerous lesion of the internal angle of the right eye:Cutaneous leishmaniasis is one of the causes]. Our Dermatol Online. 2018;9:203-6.

3. Paudel V, Parajuli S, Chudal D. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nepal:an emerging public health concern. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:76-8.

4. Ul Bari A, ber Rahman S. Correlation of clinical, histopathological, and microbiological findings in 60 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:28-32.

5. Tamer F, Yuksel ME. A distinct cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion on the tip of the patient’s nose:A visual warning for European colleagues. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:108-9.

6. Thakur L, Singh KK, Kushwaha HR, et al. Leishmania donovani infection with atypical cutaneous manifestations, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1864-9.

7. Ul Bari A, Raza N. Lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis:A report of 16 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:85.

8. Kabir S, Teimoorian M, Mahdavi M, Tayyebi Meibodi N, Tajalli M, Mashayekhi Goyonlo V, et al. A solitary erythematous papule on the nose. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:663-5.

9. Gatti GL, Freda N, Stabile M, Giacomina A, Balmelli B, Boileau R, et al. Deforming mucocutaneous leishmaniasis of the nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e446-7.

10. Gurel MS, Tekin B, Uzun S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis:A great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:140-51.

11. Garrido-Jareño M, Sahuquillo-Torralba A, Chouman-Arcas R, Castro-Hernández I, Molina-Moreno JM, Llavador-Ros M, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis:experience of a Mediterranean hospital. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:24.

12. Frikha F, Bahloul E, Masmoudi A, Amouri M, Turki H. Chancriform penile cutaneous leishmaniasis. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:94.

13. Morales AC, Garcia MP. Leishmaniasis:an unforgettable disease [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 13]. Am J Med. 2020;S0002-9343:30676-8.

14. Meireles CB, Maia LC, Soares GC, Pinheiro Teodoro IP, do Socorro Vieira Gadelha M, da Silva CGL, et al. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis:A systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;172:240-54.

15. Santos RCD, Pinho FA, Passos GP, Larangeira DF, Barrouin-Melo SM. Isolation of naturally infecting Leishmania infantum from canine samples in Novy-MacNeal-Nicolle medium prepared with defibrinated blood from different animal species. Vet Parasitol. 2018;257:10-4.

16. Wollina U, Koch A, Bitel A. Deep chronic cutaneous New World leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis and trichinellosis in a German returnee from Ecuador. Our Dermatol Online. 2019;10:272-4.

17. Parajuli N, Manandhar KD, Shrestha S, Bastola A. Cutaneous leishmaniasis of lip and role of polymerase chain reaction:a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2020;58:494-6.

18. Veraldi S, Bottini S, CurròN, Gianotti R. Leishmaniasis of the eyelid mimicking an infundibular cyst and review of the literature on ocular leishmaniasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14 Suppl 3:e230-2.

19. Ahmad S, Suleiman H, Al-Shehabi Z. A successful treatment of severe lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis in an elderly man:a case report. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2020;2020(8):omaa064. Published 2020 Aug 10. doi:10.1093/omcr/omaa064

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3211-1736 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3211-1736 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4141-5520 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4141-5520 |

Comments are closed.