Carbamazepine-induced pellagra: Dermoscopic findings and response to oral nicotinamide

Shagufta Rather , Saika Reyaz, Aaqib Aslam Shah, Malik Nazim

, Saika Reyaz, Aaqib Aslam Shah, Malik Nazim

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Government Medical College, Srinagar, University of Kashmir, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2023. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Pellagra is a nutritional disorder characterized clinically by the four Ds: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and severe systemic photosensitivity manifesting as death. The disorder results from a deficiency of niacin or its precursor tryptophan and is mainly associated with compromised dietary intake of niacin and tryptophan or excessive intake of leucine (a natural antagonist). Other causes include chronic alcohol intake, malabsorption, metabolic disorders, and the administration of certain medications. Herein, we report the clinical and dermoscopic findings in a twenty-year-old male with seizure disorder presenting with carbamazepine-induced pellagrous dermatitis that resolved after the administration of niacin.

Key words: Pellagra; Photosensitivity; Carbamazepine; Dermoscopy; Niacin

INTRODUCTION

Pellagra is a systemic nutritional disorder caused by a deficiency of vitamin B3 (niacin), which is an essential component of several coenzymes. Pellagra is characterized by the four Ds: photosensitive dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death. Death is included as a cardinal clinical feature in this photosensitivity syndrome [1]. Herein, we present the case of a twenty-year-old male with seizure disorder who had developed carbamazepine-induced dermatitis, which resolved with niacin therapy.

CASE REPORT

A twenty-year-old male presented to the skin outpatient department with complaints of itchy, red, raised lesions on the face, neck, and dorsum of the hands persistent for the last one month as well as oral lesions in the form of inflammation and fissuring at the angles of the mouth with difficulty in opening the mouth and ingesting spicy meals. The itching and burning sensation aggravated on sun exposure. He had a medical history of seizure disorder, for which he had been receiving levetiracetam for the last ten years and carbamazepine for the last three years. There was no history of fever, loose motions, pain in the abdomen, gastrointestinal surgery, or afflicted mental faculties. He denied exposure to chemical agents, contact allergens, and home remedies.

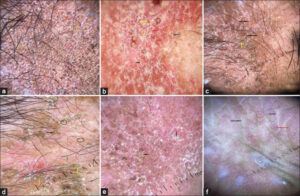

General and systemic examinations were normal. A dermatological examination revealed well-demarcated, symmetric, erythematous to hyperpigmented, dry, and scaly plaques of a yellowish-brown hue on the face, nape, sides of the neck, and dorsa of the hands (Figs. 1a – 1d) with a sharp demarcation at the wrist joint (glove sign or gauntlet sign). A mucous examination revealed commissural cheilitis and glossitis. Routine hematological and biochemical investigations were within the normal ranges. Serology for anti-nuclear antibodies was negative. Dermoscopy of the skin lesions with DermLite DL4 in the non-polarized and polarized mode revealed peripheral double-edged, white scale detached from outward inward, perifollicular scaling, reddish-brown polygonal areas and structures, white, follicular dots, follicular plugs, and red and brown dots and globules on a pinkish background. Short, linear, arborizing vessels and dotted vessels were also observed in the polarized mode (Figs. 2a – 2f).

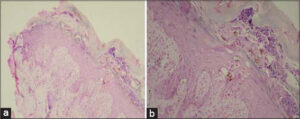

The histopathological findings observed were hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, marked vacuolar changes in the upper half of the stratum Malpighian layer, and increased pigment throughout the layers of the epidermis (Figs. 3a and 3b).

|

Figure 3: (a-b) Hyperkeratosis, mild spongiosis, acanthosis, increased basal layer pigmentation; the dermis showing edema with perivascular chronic inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, 4×). |

The estimation of serum niacin could not be performed due to financial constraints. Based on the history and physical examination, a diagnosis of drug-induced pellagra-like dermatitis was established. The patient was started on tablets of nicotinamide 300 mg daily in three divided doses with a multivitamin B complex. Carbamazepine was discontinued. The lesions healed completely within two weeks of nicotinamide therapy (Figs. 1e and 1f). Proper nutrition with a high-protein diet and physical sunscreen cream were also added to the treatment protocol.

DISCUSSION

Gaspar Casal first described pellagra among the poor peasants of the Asturias province of Spain in 1735. In vernacular Italian, pellagra means rough or sour skin and refers to the thickened skin observed in patients suffering from the condition.

Niacin (vitamin B3) is essential for adequate cellular function because of its role in two similar yet distinct coenzymes (that is, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP)). Both are cofactors that may be recycled by serving as both oxidizing (NAD, NADP) and reducing (NADH, NADPH) agents. A deficiency of NAD and NADP may lead to pellagra, resulting in a classical triad of dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. Pellagra is often an evolving process, which, if untreated, may lead to progressive deterioration and death (the fourth and last “D”) over a period of years [2].

Pellagra is associated with compromised dietary intake of niacin and tryptophan or excessive intake of leucine (natural antagonist).

Other leading causes of pellagra-like dermatitis include chronic alcohol intake, individuals with significant malabsorption, certain metabolic disorders, and the administration of specific medications [2]. Drug-induced pellagra may be caused by drugs such as antitubercular drugs, 5-fluorouracil, 6-mercaptopurine, phenytoin, chloramphenicol, azathioprine, and phenobarbital. Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethionamide are structurally similar to NAD and competitively replace NAD from metabolic pathways. Hence, tissues with high-energy requirements, such as the brain, or with a high turnover rate, such as the skin and gut, are affected in pellagra [3]. The inhibited conversion of tryptophan to niacin by 5-fluorouracil leads to pellagra, and 6-mercaptopurine causes pellagra-like dermatitis by inhibiting Korenberg’s enzyme (NAD phosphorylase). The exquisite photosensitivity seen in pellagra may result from a cutaneous deficiency of urocanic acid, the accumulation of kynurenic acid, a deficiency of NAD and NADP, and altered porphyrin metabolism, which may induce a phototoxic reaction [4].

The exact mechanism by which anticonvulsants cause pellagra is unknown. The alteration of the absorption of either niacin or other related essential vitamins has been proposed as one. A direct effect of the medication or its metabolites on the synthetic pathway of niacin is also possible [5].

The cutaneous rash of pellagra is bilateral, well-defined, symmetrical, and limited to sun-exposed sites, most prominently on the dorsum of the hands, the “V” of the neck, the face, the radial aspects of the forearms, and the exposed skin on the legs and feet. Persistent erythema and scaling are sequelae of the acute eruption. Chronic lesions reveal marked hyperpigmentation, skin thickening, dryness, and roughness. Various signs described in association with pellagra are the glove or gauntlet sign, the boots sign, and the Casal’s necklace [6].

The WHO recommends 300 mg of nicotinamide given in a divided daily dose for 3–4 weeks. Parenteral nicotinamide administration of 1 g 3–4 times daily is recommended for severe cases. Nicotinamide is preferred over niacin in the treatment of pellagra as it does not cause vasomotor disturbances, such as flushing, itching, or burning [7]. Our report describes a patient with carbamazepine-induced pellagra that resolved by the replacement of niacin and other essential vitamins. Although the condition is rare, we as dermatologists should be familiar with this entity, because the skin findings are its most diagnostic feature and the condition is easily treatable.

The dermoscopy of pellagra dermatitis observed was similar to that described in an earlier report [8]. Dermoscopy as a non-invasive modality in conjunction with clinical and histopathological features and a therapeutic response may help in correcting the diagnosis.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM. Pellagra and skin. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:476-81.

2. Prabhu D, Dawe RS, Mponda K. Pellagra a review exploring causes and mechanisms, including isoniazid-induced pellagra. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021;37:99-104.

3. Nabity SA, Mponda K, Gutreuter S, Surie D, Zimba SB, Chisuwo L, Moffitt A, Williams AM, et al. Isoniazid-associated pellagra during mass scale-up of tuberculosis preventive therapy:A case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022 May;10:e705-e714. Li R.

4. Wan P, Moat S, Anstey A. Pellagra:A review with emphasis on photosensitivity. Br J Dermatol. 2011;162:1188-200.

5. Boileau M, Azib S, Staumont-SalléD, Dezoteux F. Increased risk of pellagra in an alcoholic patient treated with antiepileptic drugs. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2022;24:S0151-9638(22)00037-0.

6. Barro/TraoréF, Diallo B, Tapsoba P, Andonaba J-B, KéréM, Niamba P, et al [Pellagra:Epidemiological and clinical features in the western region of Burkina Faso]. Our Dermatol Online. 2013;4:479-83.

7. Rani R, Sharma RK, Gupta M. Zinc-responsive acral hyperkeratotic dermatosis. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13:308-10.

8. Murthy SC, Shankar M. Pellagra dermatitis:Five cases with dermoscopic findings. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:e56-8.

Notes

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0980-6014 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0980-6014 |

Comments are closed.