Quality of life of psoriatic patients in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Nomtondo Amina Ouédraogo 1,2, Patricia Felicité Tamalgo1, Fagnima Traoré3, Muriel Sidnoma Ouédraogo1,2, Gilbert Patrice Tapsoba1,2, Léopold Ilboudo4, Nadia Kaboret4, Joelle Zabsonré/ Tiendrébeogo2,5, Marcellin Bonkoungou5, Salamata Lallogo6, Séraphine Zeba7, Nessiné Nina Korsaga2,7, Pascal Niamba1,2,8, Adama Traoré1,2, Fatou Barro2,9

1,2, Patricia Felicité Tamalgo1, Fagnima Traoré3, Muriel Sidnoma Ouédraogo1,2, Gilbert Patrice Tapsoba1,2, Léopold Ilboudo4, Nadia Kaboret4, Joelle Zabsonré/ Tiendrébeogo2,5, Marcellin Bonkoungou5, Salamata Lallogo6, Séraphine Zeba7, Nessiné Nina Korsaga2,7, Pascal Niamba1,2,8, Adama Traoré1,2, Fatou Barro2,9

1Department of Dermatology-Venereology of Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital (YO UH), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2Health Science Training and Research Unit, Joseph Ki-Zerbo University, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 3Department of Dermatology, Regional University Hospital of Ouahigouya, Burkina Faso, 4Raoul Follereau Center of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 5Rheumatology Department of Bogodogo University Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 6Dermatology Unit of Saint Camille Hospital in Ouagadougou (HOSCO), Burkina Faso, 7Dermatology Unit of Boulmiougou District Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 8Dermatology unit of Medical Center of Camp Sangoulé Lamizana, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 9Department of Dermatology of Tingandogo University Hospital, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Corresponding author: Nomtondo Amina Ouédraogo, MD

How to cite this article: Ouédraogo NA, Tamalgo PF, Traoré F, Ouédraogo MS, Tapsoba GP, Ilboudo L, Kaboret N, Zabsonré / Tiendrébeogo J, Bonkoungou M, Lallogo S, Zeba S, Korsaga NN, Niamba P, Traoré A, Barro F. Quality of life of psoriatic patients in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(2):138-142.

Submission: 14.12.2021; Acceptance: 16.02.2022

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20222.4

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Psoriasis is a chronic, displaying inflammatory dermatosis. The evaluation of the psychosocial impact of chronic dermatoses on the quality of life of patients may help to orientate the objectives of management in order to improve their daily life, hence the interest of our study with the objective to evaluate the impact of psoriasis on the quality of life of patients followed in the dermatology, venereology, and rheumatology departments of the city of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

Patients and Method: This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study that took place from March 1 to June 28, 2019, in six public hospitals in the city of Ouagadougou. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) were the quality of life tools employed for this study.

Results: Forty-eight (48) patients with psoriasis met the inclusion criteria. The mean age of the patients was 46.20 years, ranging from 22 to 79 years. There were 18 females and 30 males, with a sex ratio of 1.6. The measurement of the patients’ QoL by the DLQI reported a mean score of 9.14 out of 30. There was a low impact of the disease on the QoL for seventeen patients. The evaluation of the QOL with the PDI noted an alteration of daily activities (3.95/15) and alteration of the patients’ psychosocial relationships (2.66/18). The analysis of the QoL according to sociodemographic and clinical variables noted an alteration significantly related to age, level of education, and severity of the disease. An alteration in professional relationships was significant in female patients. An alteration in the different dimensions of the QoL was more significant in patients with a low level of education. The duration of the disease seemed to have no impact on the patients’ quality of life. Daily activities were significantly altered for patients with a PASI between 7 and 10. The DLQI did not correlate with disease severity (PASI) (r = 0.228; p = 0.120), unlike the PDI (r = 0.371; p = 0.009).

Conclusion: The QoL of psoriatic patients in Ouagadougou seemed to be slightly altered. This alteration was more significant for females. Professional relationships were altered for young subjects while daily activities were altered for those older.

Key words: PASI; DLQI; psychosocial impact; quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis characterized by erythematous, squamous lesions related to hyperproliferation of keratinocytes with accelerated epidermal turnover and aberrant differentiation [1]. The pathogenesis of psoriasis is complex and may be attributed to factors such as genetics, immunology, and environmental triggers. The importance of inflammasomes as part of innate immunity in the pathogenesis of psoriasis is also discussed in the literature [2]. It is a display dermatosis that may have an impact on the patient’s quality of life [3–5].

Health-related quality of life may be defined as the set of health-related conditions that diminish well-being and performance and interfere with social roles and/or alter the subject’s psychological functioning [4].

Assessing the psychosocial impact of chronic dermatoses on the patient’s quality of life may help to guide management goals to improve their daily experience [5,6]. Numerous studies on the quality of life of patients with psoriasis have been conducted worldwide, particularly in Latin America, Europa, and Asia [1,3–5,7]. They reported a significant impairment in the quality of life of psoriatic patients, with a high prevalence of depressive symptoms. In West Africa, there are few studies on the quality of life of psoriatic patients [5], hence the interest of our study, with the objective to evaluate the impact of the disease on the quality of life of psoriatic patients followed in the dermatology, venereology, and rheumatology departments of the city of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study that took place from March 1 to June 28, 2019, in six public hospitals in the city of Ouagadougou: Yalgado Ouedraogo University Hospital (YOUH), Tingandogo University Hospital (TUH), Bogodogo University Hospital (BOH), Saint Camille Hospital of Ouagadougou (SCHO), Raoul Follereau center (RFC), and Medical Center of Camp Sangoulé Lamizana (MCSL). The patients included in the study were those followed in the dermatology and rheumatology departments of these hospitals for psoriasis, aged at least eighteen years, and consenting.

A questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic and clinical data. The Wallace rule of nines was employed to calculate the body surface area (BSA). The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) was employed to assess disease severity. The Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were employed to assess quality of life [8–10].

The data collected was analyzed by Epi Info, version 7.2.2.6, and SPSS Statistics, version 20. For the comparison of variables, the Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared test was employed. The ANOVA test allowed the comparison of more than two variables. The p probability was significant at p < 0.05. The Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to investigate the relationship between the different tools, with a significant probability for p < 0.01.

The study respected the rules of ethics and deontology in the conduct and analysis of the data.

RESULTS

Forty-eight (48) patients with psoriasis met the inclusion criteria for the study. The two oldest dermatology facilities, YOUH and Raoul Follereau Center, accounted for half of the patients (24/48).

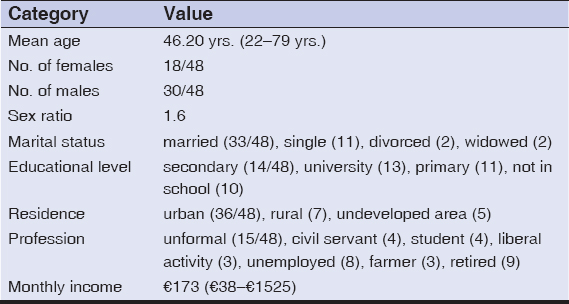

Sociodemographic Characteristics

The average age of the patients was 46.20 years, ranging from 22 to 79 years. There were eighteen females and thirty males, with a sex ratio of 1.6. Thirty-three patients were married, fifteen were single, four were divorced or widowed. In terms of educational level, 27 patients had at least secondary education. As for place of residence, 36/48 lived in urban areas. With regard to occupation, eleven patients worked in the informal sector in precarious and irregular jobs. The average monthly income was €173, ranging from €38 to €1525 (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients |

Clinical and Therapeutic Characteristics

The average duration of the disease was 7.91 years, ranging from six months to forty years. All patients reported pruritus, ten reported asthenia, and five reported insomnia. The disease was in remission for 31 patients. The number of relapses varied from one to five per year.

The triggers for psoriatic flareups were stress, seasonal variation, and emotional shock in twenty, eight, and six patients, respectively. The lesions were erythematous and squamous. The average body surface area affected was 17.89%, ranging from 1% to 90%. Thimble-like nail involvement was visible in four patients.

Thirty-four patients were on topical treatment (dermocorticoid + keratolytic), ten were on methotrexate, and eleven had no treatment.

The mean severity score (PASI) was 6.26 out of 72, corresponding to mild psoriasis, ranging from 0.1 to 39.9. Psoriasis was mild (PASI < 7) in 33 patients, moderate (7 ≤ PASI ≥ 10) in six, and severe (PASI > 10) in nine.

Quality of Life (QoL)

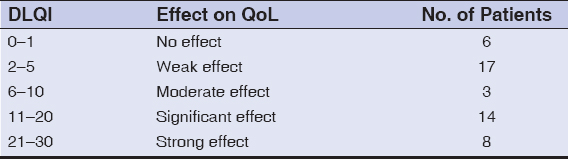

The measurement of the patients’ QoL by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) yielded a mean score of 9.14 out of 30. Seventeen patients reported a low impact of the disease on QoL. Fourteen patients reported a significant impact and eight reported an extremely significant impact. For six patients, the disease had no impact on QoL (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Quality of Life assessment by the DLQI |

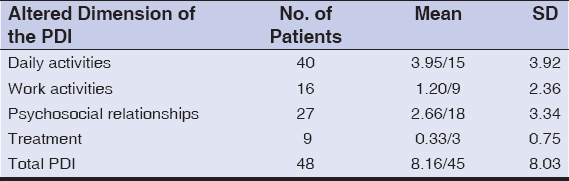

The Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI) assessment of QoL revealed an alteration in daily activities of 3.95/15 and in the psychosocial relationship between the patient and their environment at 2.66/18 (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Quality of Life assessment by the PDI |

The analysis of QoL according to sociodemographic and clinical variables revealed an alteration significantly related to age, level of education, and severity of the disease. Thus, QoL was altered for older patients and this alteration concerned all dimensions: daily activities, professional relationships, psychosocial relationships, and the type of treatment used (P = 0.00) (Table 4). The alteration in work relationships was significant for female patients. The alteration of the QoL was more significant for patients with a low level of education. The duration of the disease seemed to have no impact on the patients’ QoL. Activities of daily living were significantly altered for patients with a PASI between 7 and 10.

|

Table 4: The relationship between QoL and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics |

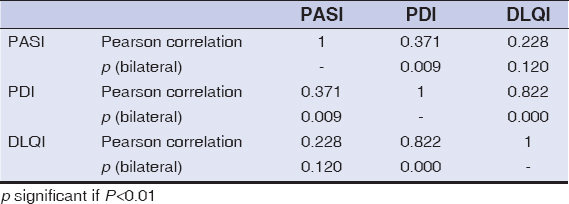

The correlation between the two QoL assessment tools (DLQI and PDI) was significant (r = 0.822; p = 0.000) (Table 5). The psoriasis-specific tool (PDI) was significantly correlated with disease severity (PASI) (r = 0.371; p = 0.009). No significant correlation was found between the DLQI and the PASI (r = 0.228; p = 0.120). There was a weak positive correlation between the treatment and the alteration in QoL, as measured by the PDI scale (r = 0.289; p = 0.046). The treatment, therefore, had a weak impact on the patients’ QoL.

|

Table 5: The correlation between the DLQI, PDI, and PASI |

DISCUSSION

The majority of the group studied had an average level of education, working in the informal sector with precarious jobs, with an average monthly income of €173, higher than the country’s guaranteed minimum wage of €149. It was mainly males, consisting of young adults with an average age of 46 years. These characteristics were similar to studies done by Karelson in Estonia in 2013, Garcia-Sanchez in Mexico in 2017, Nuynt in Malaysia in 2015, Maoua in Tunisia, and Gruchala in Poland [11–14]. Karelson noted a lower mean age (38.30 years), while Garcia-Sanchez reported older patients (51.22 years). Nuynt reported 188/223 patients with at least a secondary school level. Garcia- Sanchez reported 17/72 patients with at least secondary education [12]. Maoua, in their work on QoL and work activity on 58 patients, reported that 62% had a primary, lower level of education [13].

The average PASI in our study was low (6.26). Other authors made the same observation, notably Bronckers in the Netherlands in 2018 with a cohort of 75 patients, Nyunt in Malaysia with 223 patients, and Maoua in Tunisia with 58 cases [10,13,15].

The DLQI was reported to be low (9.14/30) for the majority of the patients. Our result was comparable to that by Amine in Morocco in 2017 with a mean DLQI of 8 [16].

Sof in Oujda, Morocco, also reported a low DLQI (10.20) for all dermatology patients in the hospital in general [7]. However, patients suffering from severe psoriasis had a high DLQI (16.6) [7,17–19]. This was the case of Jung in South Korea in 2018, who found a mean DLQI of 12.4 [20]. Maoua in Tunisia in 2015 noted a mean DLQI score of 16.1 [13].

The DLQI was not correlated with the PASI (r = 0.228; p = 0.120), unlike the psoriasis-specific tool PDI (r = 0.371; p = 0.009). Maoua found a significant correlation between the DLQI and the PASI (r = 0.38; p = 0.003) [13]. Moradi in Iran in 2015 also found that low DLQI scores were associated with high PASI scores (r = 0.58; p < 0.05) [19]. This discordance between the DLQI and PASI suggests that the assessment of QoL for psoriasis should necessarily include psychological and social dimensions.

The assessment of QoL by the PDI showed that the patients’ daily activities were altered more significantly, followed by psychosocial relationships and work activities.

The alteration in QoL was greater in females (p = 0.04). We explain this by the fact that females tend to be more concerned about their appearance. This result is comparable to that reached by Garcia-Sanchez in Mexico in 2017, who found that QoL was more affected in females (58.2%) [12].

There was an association between the alteration in daily and occupational activities and the patient’s age (p = 0.00). Patients with an age of 15–29 years were the most professionally affected. This could be explained by the fact that this tends to be the time of the most intensive job searching and showing overt psoriasis lesions may interfere or hinder in receiving a job [21].

A lower level of education disturbed the QoL to a greater extent (p = 0.00). Indeed, a higher level of education would allow a better understanding and acceptance of the disease. Maoua in Tunisia came to the same conclusion. In fact, for 62% of the patients with a primary level of education, the alteration in QoL was more significant (avg. DLQI = 16.1) [13]. However, Nyunt in Malaysia in 2015 found no association between education and the alteration in QoL [10].

Drug treatment should improve lesions and, therefore, the QoL of the patient [17,22–24]. In our study, treatment had a weak impact on the patient’s QoL. In addition to drug treatments, psychotherapeutic management is beneficial for patients with psoriasis, with a positive impact on QoL [21]. The patients in our study did not systematically receive psychotherapy.

Our study found a strong correlation between the two measures of QoL, the DLQI and the PDI (r = 0.822; p = 000) and the PASI.

CONCLUSION

In our study, the QoL of psoriatic patients in hospital at Ouagadougou, seemed to be slightly altered, with this alteration being more significant for females. Professional relationships were disturbed for young subjects, while daily activities were disturbed for those older. Psychotherapy may be combined with patient management to help improve the patient’s QoL.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Kim GE, Seidler E, Kimball AB. A measure of chronic quality of life predicts socioeconomic and medical outcomes in psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol. Venereol. 2015;29:249 54.

2. Sharon C, Jiquan S. Association of NLRP1 and NLRP3 gene polymorphism with psoriasis. Our Dermatol online. 2020;11:275-83.

3. Pärna E, Aluoja A, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in chronic skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:312-6.

4. Cella D. Quality of life:Concepts and definition. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1994;9:186 92.

5. Obradors M, Blanch C, Comellas M, Figueras M, Lizan L. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis:A systematic review of the European literature. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2739-54.

6. Nguyen CM, Beroukhim K, Danesh MJ, Babikian A, Koo J, Leon A. The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis:A review. Clin Cosm Invest Dermatol. 2016;9:383-92.

7. Sof K, Aouali S, Bensalem S, Zizi N, Dikhaye S. Dermatoses in the hospital and their impact on quality of life. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12:462-3.

8. Henseler T, Schmitt-Rau K. A comparison between BSA, PASI, PLASI and SAPASI as measures of disease severity and improvement by therapy in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1019 23.

9. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI):A simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210 6.

10. Nyunt WWT, Low WY, Ismail R, Sockalingam S, Min AKK. Determinants of health-related quality of life in psoriasis patients in Malaysia. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2015;27:662 73.

11. Karelson M, Silm H, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in vitiligo in an estonian sample:Comparison with psoriasis and healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:446 50.

12. Garcia-Sanchez L, Montiel-Jarquin AJ, Vazquez-Cruz E, May-Salazar A, Gutierrez-Gabriel I, Loria-Castellanoso J. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Gac Med Mex. 2017;153:185 9.

13. Maoua M, El Maalel O, Boughattas W, Kalboussi H, Ghariani N, Nouira R, et al. Qualitéde vie et activitéprofessionnelle des patients atteints de psoriasis au centre tunisien. Arch Mal Prof l’Environnem. 2015;76:439 48.

14. Gruchała A, Cisłak A, Golan?ski J. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as an alternative to C-reactive protein in diagnostics of inflammatory state in patients with psoriasis. Our Dermatol Online. 2019;10:7-11.

15. Bronckers IMGJ, Van Geel MJ, Van de Kerkhof PCM, Elke M. G. J. de Jong, Marieke M. B. Seyger. A cross-sectional study in young adults with psoriasis:Potential determining factors in quality of life, life course and work productivity. J Dermatol Treat. 2018;20:1-9.

16. Amine M, Amal S, Hocar O, Belkhou A. Psoriasis et qualitéde vie. 2017;14:118.

17. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157:238 44.

18. Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:236 44.

19. Moradi M, Rencz F, Brodszky V, Moradi A, Balogh O, Gulácsi L. Health status and quality of life in patients with psoriasis:An Iranian cross-sectional survey. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:153 9.

20. Jung S, Lee S, Suh D, Shin HT, Suh D. The association of socioeconomic and clinical characteristics with health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis:A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcom. 2018;16:180-8.

21. Gruchała A, Marski K, Zalewska-Janowska A. Psychotherapeutic methods in psoriasis. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:113-9.

22. Adil M, Singh PK, Sonkar VK, Chahar YS, Kumar P, Swetank. Omega-3 fatty acids and quality of life in psoriasis:An open, randomised controlled study. Our Dermatol Online. 2019;10:12-6.

23. Kara YA. Treatment with intralesional methotrexate injection in a patient with nail psoriasis. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13:62-4.

24. Kawshar T, Rajesh J. Sociodemographic factors and their association to prevalence of skin diseases among adolescents. Our Dermatol Online. 2013;4:281-6.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0734-0759 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 |

Comments are closed.