PowerPoint presentations (PPP): From A to Z

Prateek Sharma1, V Ramesh2, Khalid Al Aboud 3

3

1Department of Dermatology, Safdarjang Hospital, New Delhi, India, 2Professor & Head, ESI Medical College, Faridabad, India, 3Department of Dermatology, King Faisal Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

Corresponding author: Khalid Al Aboud, MD

How to cite this article: Sharma P, Ramesh V, Al Aboud K. PowerPoint presentations (PPP): From A to Z. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(2):233-236.

Submission: 13.09.2021; Acceptance: 19.11.2021

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20222.34

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

PowerPoint presentations (PPPs) remain one of the most popular and efficient tools for education, teaching, and training in medicine and other sciences. Despite its widespread use, not all know its secrets and have mastered its techniques. The aim of this report is to provide an updated review for dermatologists and other healthcare providers about PowerPoint presentations.

Key words: education; dermatology; medicine; teaching; training

INTRODUCTION

In the last several decades of the twentieth century, an overhead projector was a great option for giving presentations. One could write the main points on a transparent sheet and project it onto a screen, including drawings and graphs. Alternatively, slides incorporating such information could be projected on a screen with a carousel. The limitations included carrying these and the inability to share or make changes later. The 1990s heralded the era of PowerPoint presentations (PPPs), which have relegated these to history. Toward the end of the second millennium, when the digital mode took over numerous tasks, PPPs became the sine qua non in almost every form of activity.

PPPs refer to presentations made with a PowerPoint slideshow projected from a computer. It allows for the systematic presentation of a clinical subject followed by structured feedback from the audience.

PPPs carry numerous advantages as it is a condensation of the source material by which the reader may assimilate information in a short time and record it through screenshots and video recording.

Some obstacles, however, may limit the delivery of an effective presentation, for instance:

- Lack of clarity;

- Not knowing the supervisor’s expectations [1];

- Limited data outlining the established standards for effective presentations [2].

This article outlines key points constituting an effective PPP as an efficient mode of skills assessment to promote competency-based medical education.

Preparation

In the time allotted for a PPP, one has to condense surplus information into a format that fulfills the criteria of being appropriate, accurate, comprehensible, well-executed, interesting, and memorable [3].

Content

1. Layout

The first slide should display the title, the presenter’s name, and affiliation. This should be followed by an introductory slide and one outlining the main contents [4]. The last slide should be the concluding slide.

Each slide should be self-explanatory, with a title and a uniform, dark background (blue, green, or purple) [5].

2. Font characteristics

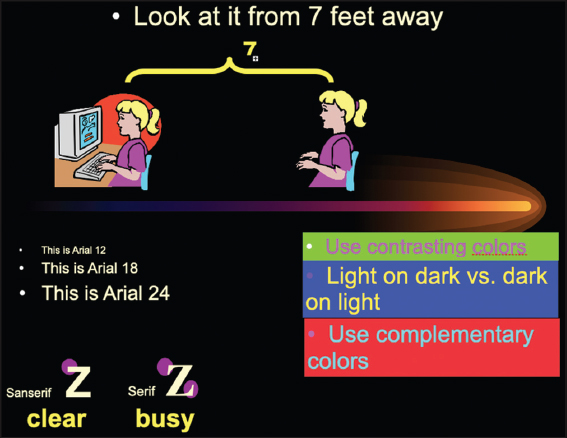

Size: It is preferable to use a minimum of an 18-point font for the slide text and a minimum font size of 36 points for the slide title [6] (Fig. 1).

|

Figure 1: Important tips for slide formatting and content [11]. |

However, this may vary depending on the place of presentation. For instance, if the presentation is shown in a large room in front of several hundred people, fonts should be extra-large to enable those in the back to read without difficulty. In a small room, medium-to-large fonts should suffice.

Character: A sans-serif font such as Arial, Helvetica, or Tahoma should be used, as Times New Roman may be hard to read [7].

Color: A contrasting color of the text as compared to the background makes the presentation more readable. The title font and the keywords or sentences should be highlighted with a different color.

Format: One must write telegraphic sentences, possibly except for the conclusions. Articles such as a, an, and the should be skipped. Bullets may be used to highlight different points.

One must be wary of using:

- More than two different types of fonts;

- More than four different font colors;

- More than six lines of text per slide;

- More than eight words per line of text;

- Flashy colors or templates of fonts or slide layouts [8].

3. Charts, graphs, and tables

Whenever possible, one must use graphs and charts instead of tables and simplify the presented data.

4. Images

Faces, if shown, should be masked to prevent identity threat. Pictures depicting treatment should show the same area before and after therapy. When scanning an image for the full screen, the image should be scanned at 480 × 640 pixels at 72 to 96 dpi in JPEG format [9].

5. Animation

An animation tool may be employed to display texts and graphics entering or exiting the slide in a lively manner. However, one must keep in mind that excessive animation may be both superfluous and distracting [10].

6. Inserting screen captures and screen recordings

PowerPoint 2013 and later versions allow for the inclusion of static screen captures or screen recordings from one’s computer device, serving as a useful tool for enhancing the scope and quality of the presentation.

7. References

It is ethical to acknowledge the resources used for compiling the content and ensure no infringement of copyright laws.

ON THE DAY OF PRESENTATION

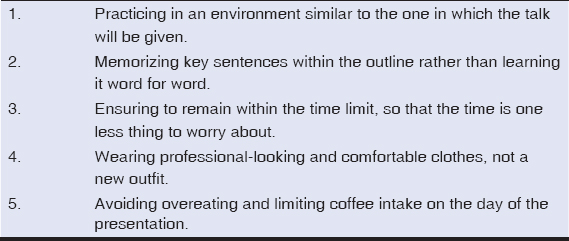

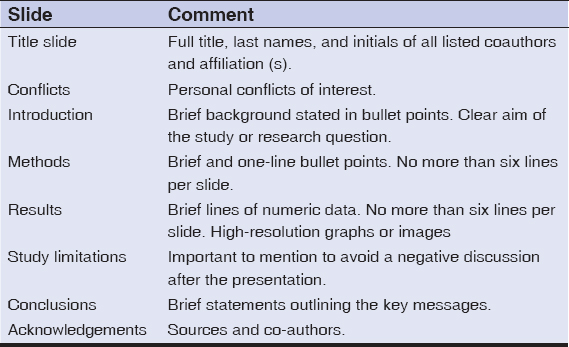

Table 1 and Table 2 contain some remarks for a better presentation.

|

Table 1: Acceptable format of a presentation based on an original paper [14] |

|

Table 2: Tips on remaining calm and confident on the day of the presentation [15] |

One may arrive early on the day of presentation to test equipment to be used.

Making backup copies in at least two different places with printed handouts is helpful in the rare event of equipment failure, in which the presentation may have to be given without visual aids.

A useful tip during rehearsing is to visualize the audience sitting in front of oneself and imagining delivering the presentation with enthusiasm and leaving the room knowing that it was a first-rate presentation [12]. Practicing with a friend or family member who may provide healthy feedback is also worthwhile.

Some general principles of a systematic clinical presentation are as follows:

- Giving an outline at the beginning and having a good introductory or outline slide to grab the attention of the audience;

- Following a logical sequence: starting with broader, more general topics and going progressively deeper;

- Speaking slowly, loudly, and clearly in an engaging tone, giving appropriate pauses in between;

- Discussing only one concept per slide;

- Each slide taking around 45 to 60 seconds for discussion, with not more than fifteen slides for a ten-minute talk [9];

- Moving at appropriate times during the presentation and ensuring that gestures are natural and in sync with what is being said;

- Not apologizing for minor interruptions in the flow of the presentation;

- Maintaining good eye contact with the audience by glancing at their faces for 3–5 seconds and then moving on to the next person [12];

- Observing the audience for any lapse of attention due to excessive content and trying work on that for future presentations;

- Stories that appeal to the audience’s emotions, particularly if delivering lectures for students, helping to bring the point across;

- Concluding by restating the main objective and key supporting points and prompting for questions.

When asked a question, one must first thank that member of the audience and keep answers short and succinct [13].

During conferences, short times are often allotted to the invited speakers, who have to presume that the audience possesses a basic knowledge of the subject and expects to listen to novel or exciting content. One may present a brief introduction and swiftly proceed to emphasize the latest innovations and the scope for further research, which will consistently hold the audience’s attention [14].

CONCLUSION

With educational technology and smart classes becoming increasingly popular, education becomes more interactive, engaging a large number of students in taking advantage of the digital mode. Clinical presentations, if prepared and presented proficiently, may significantly augment teaching, learning, and assessment in an engaging and comprehensive manner, thereby promoting the multi-faceted professional growth and development of the clinician.

REFERENCES

1. Green EH, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe BA, Hershman W. The oral case presentation:What internal medicine clinician-teachers expect from clinical clerks. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:58-61.

2. Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills:A rhetorical analysis with pedagogical and professional implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:308-14

3. Cheek JG, Beeman CE. Using visual aids in extension teaching. 1991. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/scripts/htmlgen.exe?DOCUMENT_MG098 [Accessed on 28, September 2000]

4. Forsyth R, Waller A. Making your point:Principles of visual design for computer aided slide and poster production. Arch Dis Child. 1995;72:80-4.

5. Dalal MD, Daver BM. Computer generated slides:A need to curb our enthusiasm. Br J Plast Surg. 1996;49:568-71.

6. Banks JE. How to build a better presentation. 2000. http://www. newmediacomm.com/Artic_BBP.html [Accessed on 28, September 2000]

7. Brown SD. Tips for building and giving technical presentations. 1999. http://www.udel.edu/chemo/C465Tips.htm [Accessed on 28, September 2000]

8. Garson A Jr, Gutgesell HP, Pinsky WW, McNamara DG. The 10-minute talk:Organization, slides, writing and delivery. Am Heart J. 1986;111:193-203.

9. Sahu DR, Supe AN. The art and science of presentation:35-mm slides. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46:280.

10. Tarpley MJ, Tarpley JL. The basics of PowerPoint and public speaking in medical education. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:129-32.

11. Chen V. Designing effective powerpoint presentations. ERAU. Accessed on 2/6/21. <https://www.ncsl.org/documents/seminars/effective_powerpoint_presentations.ppt >

12. Dolan R. Effective presentation skills. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017;364:fnx235.

13. Wellstead G, Whitehurst K, Gundogan B, Agha R. How to deliver an oral presentation. Int J Surg Oncol (NY). 2017;2:e25.

14. Alexandrov A. How to prepare and deliver a scientific presentation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:202-8.

15. Fleming N. How to give a great scientific talk. Nature. 2018;564:S84-5.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7292-0736 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7292-0736 |

Comments are closed.