Necrobiosis lipoidica in a non-diabetic female with extensive vitiligo: An uncommon association

Ipshita Bhattacharya , Paschal Dsouza, Kanchan Dhaka, Tapan Kumar Dhali

, Paschal Dsouza, Kanchan Dhaka, Tapan Kumar Dhali

Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy, ESI-PGIMSR, New Delhi, India

Corresponding author: Ipshita Bhattacharya, MD

How to cite this article: Bhattacharya I, Dsouza P, Dhaka K, Dhali TK. Necrobiosis lipoidica in a non-diabetic female with extensive vitiligo: An uncommon association. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(2):175-178.

Submission: 30.07.2021; Acceptance: 17.10.2021

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20222.14

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD) is a chronic non-infectious granulomatous disease characterized by sclerodermiform plaques, papules, or inflammatory nodules. NLD may be associated with diabetes mellitus (DM), sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. While reports of patients having NLD, DM, and vitiligo at the same time exist, there are, to the best of our knowledge, no reports of the cooccurrence of NLD and vitiligo in the absence of evidence of DM. Herein, we report a 57-year-old, non-diabetic vitiligo patient, who had developed yellowish-brown plaques over bilateral shins with central scarring and atrophy. Histopathology was compatible with NLD. While there is a case report of a patient having psoriasis, NLD, DM, and vitiligo concurrently, this case, having NLD and vitiligo without clinically evident DM, is prominent. Since around 20–40% of cases of vitiligo may have metabolic syndrome, this case draws attention to the possible overlap in pathogeneses and the need for the intensive monitoring of such patients.

Key words: Necrobiosis lipoidica; Vitiligo; Metabolic syndrome; Dermatology

INTRODUCTION

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a chronic, non-infectious granulomatous disease characterized by sclerodermiform plaques, papules, or inflammatory nodules, which typically affect the shins. Around 12.5–70% of cases of NL have been reported to be associated with diabetes mellitus (DM) [1]. NL is also known to be associated with a myriad of dermatoses, including sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroid disease, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease), and post-jejunal bypass operations [2,3].

Vitiligo is an acquired, idiopathic, depigmenting skin disease characterized by the progressive loss of dihydroxyphenylalanine-positive melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis. Recently, vitiligo has been reclassified as a systemic disease rather than a depigmenting disorder [1].

While there exists a report of a patient suffering from NL, DM, and vitiligo at the same time [4], there are, to the best of our knowledge, no reports of the cooccurrence of NL and vitiligo in the absence of evidence of DM. Herein, we report such a case and further discuss the implications and conclusions that we may derive therefrom.

CASE REPORT

A 57-years-old female reported to the dermatology OPD with asymptomatic, gradually enlarging, red, and raised lesions and yellowish areas of discoloration over bilateral lower limbs present for the past six months. The patient had been a known case of hypertension for the past one year, controlled with enalapril 5 mg OD. There was no overt history of DM or thyroid disorders in the patient’s or the patient’s family.

A general examination revealed vitals in the normal range. The waist circumference was 92 cm (normal: < 88 cm). The patient also had extensive generalized vitiligo.

A local examination revealed a single reddish-brown, well to ill-defined, annular plaque, around 9 × 3 cm in size, present over the right shin with sharply demarcated, irregular, elevated borders with slight induration. Central scarring and atrophy were noted along with superficial, fine, adherent scales. Telangiectasias were also noted. Patchy areas of yellowish-brown discoloration were present over the bilateral shin, some coalescing over the left shin (Fig. 1). No hair loss over the lesions was noted. Cutaneous sensations were intact.

|

Figure 1: Yellowish-brown, well to ill-defined, annular plaques over the bilateral shin with central scarring and atrophy. |

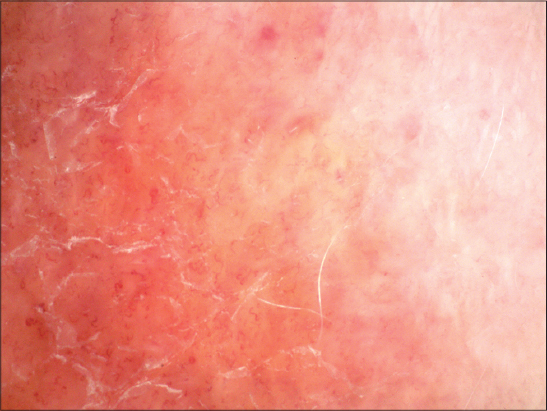

A dermoscopic examination further revealed telangiectasias, white areas of collagen degeneration, and yellowish-brown patches of inflammation (Fig. 2).

|

Figure 2: Dermoscopy revealing telangiectasias, white areas of collagen degeneration, and yellowish-brown patches of granulomatous inflammation. |

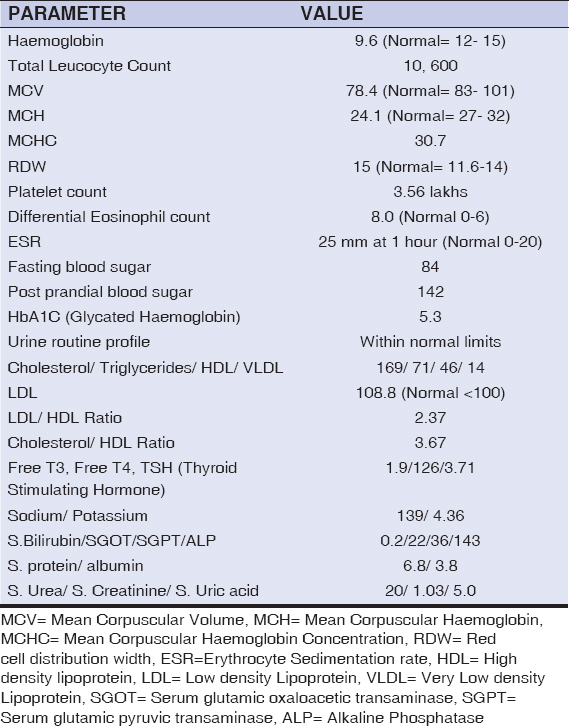

Hemogram was suggestive of iron deficiency anemia. A slightly raised eosinophil count and ESR were noted. Blood sugar, HbA1c levels, and urine routine microscopy were normal. A lipid profile revealed a mild increase in LDL (108.8; normal: < 100). Electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, serum protein levels, and a thyroid function test were within normal ranges (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Lab investigations. |

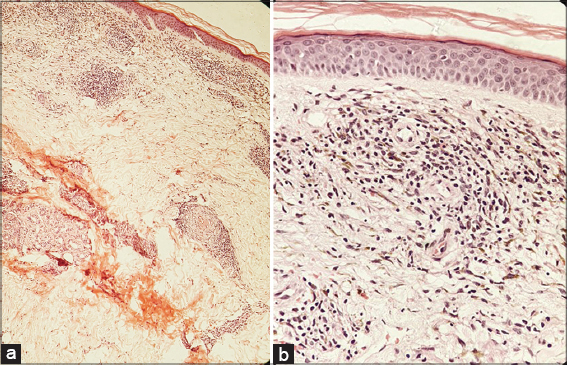

A histopathological examination revealed mild hyperkeratosis in the epidermis (Figs. 3a and 3b). The upper dermis, lower dermis, and subcutaneous tissue showed perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with occasional eosinophils. The infiltrate was more pronounced in the deeper layers. Mild septal panniculitis was present. Upon clinicopathological correlation, a diagnosis of NLD was established.

|

Figure 3: (a and b) Upper dermis, lower dermis, and subcutaneous tissue showing perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with occasional eosinophils on histopathology (10× and 40×). |

DISCUSSION

NL was first described by Oppenheim [5] in 1929, naming it dermatitis atrophicans diabetica, which was later renamed as NLD (necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum) by Urbach [6].

The first case of NL in a non-diabetic patient was reported by Goldsmith in 1935 [7].

The average age of onset of NL is thirty years, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1. It is widely recognized for its association with diabetes mellitus, occurring in around 0.3–1% of cases of the same [8,9]. As high as 65% of NL patients are clinically diabetic while the remaining have a high likelihood of demonstrating abnormal glucose tolerance or a positive family history of DM. DM is usually moderately severe or severe, with 50% of cases reporting diabetic angiopathic stigmata of end-organ damage, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. These complications, along with the relatively earlier age of onset of NL in diabetics than their non-diabetic counterparts, highlight the accelerated diabetogenic forces operative in patients with NL [9].

Though NL presents a strong association with DM, it is not directly related to hyperglycemia, glucosuria, or control of DM (including HbA1c levels), but its onset prior to the occurrence of detectable carbohydrate abnormalities makes it an important clinical marker of prediabetes [9,10].

Among several dermatological associations of DM, vitiligo is reported to account for around 5.7–10% of cases [11,12].

Vitiligo has a three-pronged pathomechanism that eventually triggers insulin resistance [1]:

- The presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNFa);

- Autoimmune dysfunction and lipid peroxidation, leading to the deterioration of reactive oxygen species, which reduces melanocytes in adipose tissue;

- Elevated homocysteine levels.

Further, vitiligo patients have been reported to have a deranged lipid profile (increased LDL and decreased HDL). The above features highlight the higher risk of metabolic syndrome that these patients might face [1].

Metabolic syndrome is a composite of risk factors: abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. Around 25% of the world’s population is affected by metabolic syndrome, with a significant subpopulation linked to inflammatory skin diseases, such as vitiligo, scleredema, Behçet’s disease, rosacea, NL, granuloma annulare, skin tags, knuckle pads, and eruptive xanthomas [1,13].

Abraham et al. previously reported a case of a diabetic patient having psoriasis, NL, GA, vitiligo, and skin infections (recurrent erysipelas and mycotic infections) [4]. Our case, having NLD and vitiligo without clinically evident DM, is prominent, being different from those previously reported in the literature.

It is, hereby, being highlighted that NL and vitiligo have certain similar underlying pathomechanisms and there is a possibility of an overlap wherein both diseases might present with the partial manifestation of DM or metabolic syndrome, that is, when the patient meets only some of the diagnostic criteria, yet not enough to be labeled as the above case. While our patient had no overt DM, she did have some features that could have predisposed her to frank metabolic syndrome in the future, that is, hypertension, an increased waist circumference, and raised LDL. Since vitiligo also has an association with DM, this patient should be under observation for the future development of DM. Hence, the presence of NL in vitiligo should make the dermatologist more watchful.

CONCLUSION

It is recommended that all cases of NL without DM should be evaluated for possible underlying causes, including metabolic syndrome, which should be excluded. These patients should also be regularly followed up for yearly diabetes screening. Patients with vitiligo having risk factors for metabolic syndrome, such as an increased waist circumference, should also undergo evaluation for the same. At this stage, where the disease is still in evolution, counseling regarding behavioral and lifestyle changes is imperative. Intervention at this stage could substantially decrease the risk of developing undetected, uncontrolled DM later in life, complications of end-organ damage of DM, and complications of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Seremet S, Gurel MS. Miscellaneous skin disease and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:94-100.

2. PeyríJ, Moreno A, Marcoval J. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:87-89.

3. Lowitt MH, Dover JS. Necrobiosis lipoidica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:735-48.

4. Abraham Z, Lahat N, Kinarty A, Feuerman EJ. Psoriasis, necrobiosis lipoidica, granuloma annulare, vitiligo and skin infections in the same diabetic patient. Journal Dermatol. 1990;17:440-7.

5. Oppenheim M. Eigentümlich disseminierte Degeneration des Bindegewebes der Haut bie einem Diabetiker. Z Hautkr. 1929;30:179.

6. Urbach E. Beiträge zu einer physiologischin und pathologischen Chemie der Haut:Eine neue diabetische Stoffwechseldermatose. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1932;166:273.

7. Goldsmith WN. Necrobiosis lipoidica. J R Soc Med. 1935:363-364.

8. Cohen O, Yaniv R, Karasik A, Trau H. Necrobiosis lipoidica and diabetic control revisited. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46:348-50.

9. Muller SA, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum:A clinical and pathological investigation of 171 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:272-81.

10. Dandona P, Freedman D, Barter S, Majewski BB, Rhodes EL, Watson B. Glycosylated haemoglobin in patients with necrobiosis lipoidica and granuloma annulare. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6:299-302.

11. Ahmed K, Muhammad Z, Qayum I. Prevalence of cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:76-9.

12. Wahid Z, Kanjee A. Cutaneous manifestation of diabetes mellitus. J Pak Med Assoc. 1998;48:304-5.

13. Prasad H, Ryan DA, Celzo MF, et al. Metabolic syndrome:Definition and therapeutic implications. Postgrad Med. J. 2012;124:21-30.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1163-0780 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1163-0780 |

Comments are closed.