Pressure ulcers from prone positioning in COVID-19 patients: Developing clinical indicators in evidence-based practice: A retrospective study

Hassiel Aurelio Ramírez-Marín1, Adrian Soto-Mota2, Jorge Alanis-Mendizabal2, Juan Manuel Escobar-Valderrama2, Judith Guadalupe Domínguez-Cherit 3

3

1Department of Dermatology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA, 2Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” Mexico City, México, 3Dermatology Department, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán”, Mexico City. Mexico

Corresponding author: Judith Guadalupe Domínguez-Cherit, M.D.

How to cite this article: Ramírez-Marín HA, Soto-Mota A, Alanis-Mendizabal J, Escobar-Valderrama JM, Domínguez-Cherit JG. Pressure ulcers from prone positioning in COVID-19 patients: Developing clinical indicators in evidence-based practice: A retrospective study. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(2):120-125.

Submission: 28.12.2021; Acceptance: 15.02.2022

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20222.1

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: A notable pandemic arisen during the COVID-19 pandemic has developed globally in intensive care units, with patients developing pressure ulcers (PUs) after being ventilated mechanically in the prone position.

Objectives: The aim was to identify risk factors independently predictive of the development of PUs in adult patient populations treated with prone positioning and to evaluate a possible epidemiological association between the prevalence of PUs and specific clinical characteristics so as to develop clinical indicators for the prevention of PUs. Finally, the aim was to examine our study participants against the incidence of PUs with respect to the length of their stay.

Methods: : This retrospective study enrolled patients hospitalized during the period of May 2020 through January 2021. Data was collected from 299 patients hospitalized and having required prone positioning ventilatory therapy in critical care areas (short-stay units, emergency units, and intensive care units), all of which had developed Pus of at least grade two according to the classification system proposed by the NPUAP/EPUAP.

Results: : Patients who had developed PUs had a longer hospitalization stay overall and were more prone to die during hospitalization. Patients who developed Pus were more frequently males, with higher initial levels of CPK and ferritin.

Conclusions: The study reveals valuable information on the most important risk factors in the development of PUs due to prone positioning. We have described how the total number of days of hospitalization is significantly related to the development of PUs. Even a PU is not a life-threatening lesion, the implementation of improved positioning protocols may enhance results in critical patient care. We believe that this is a current, globally underestimated problem as the incidence of COVID-19 patients requiring prone positioning—and, therefore, at risk for PUs—is increasing daily.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; pressure ulcers; prone position; chronic wounds; dressings

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically influenced healthcare systems globally, affecting both epidemiology and the organization of patient management [1]. In a number of countries, emergency departments were suddenly put under pressure by an overwhelming number of patients with COVID-19 infection and with acute respiratory insufficiency requiring respiratory therapy in intensive care units (ICUs) [1]. Recent literature has demonstrated a variety of dermatologic manifestations among children and adults with COVID-19 [2]. Skin rashes associated with COVID-19 have primarily presented with erythematous, urticarial, and vesicular (chicken pox-like or varicelliform) manifestations [3,4]. Prolonged prone positioning (PP) is required for some surgical operations and in the management of ARDS [5]. A number of complications are known to be associated with these procedures, and researchers have identified pressure ulcers (PUs) as being a serious concern. Thus, implementing evidence-based strategies is essential for the reduction of pressure ulcers in patients treated with PP. PUs are common complications that affect at least 10% of patients in acute care [6]. PUs affect largely intensive-care patients, and their prevalence has been reported to exceed 80% in those in prone positioning [5]. Clinically, a pressure ulcer (PU) is defined by the confined destruction of a skin area and of the underlying tissue due to external pressure, leading to the necrosis of the ischemic area. These ulcers are painful and reduce quality of life significantly. They are expensive to treat, increase the risk of infections. and lead to long hospital stays. The frequent prone positioning as part of COVID-19 treatment creates an additional risk for the development of PUs in unusual topographies. The most important risk factors include immobility and reduced perfusion, which are also characteristics of patients with COVID-19 in critical condition.

As the pandemic began to be established with an increasing number of cases in March 2020, the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” (INCMNSZ) began to treat patients with COVID-19 exclusively. In this unprecedented situation, the department of dermatology noticed an increasing number of PUs as a complication in hospitalized patients. Particularly impressive is the large number of PUs in patients in intensive care units (ICUs) who needed ventilatory therapy in the prone position.

It has been argued consistently that pressure ulcer risk assessment scales need to be developed on the basis of multivariable analysis to identify factors independently associated with PU development [7].

A deepened understanding of the relative contribution that risk factors make to the development of PUs and an improved ability to identify patients at high risk of PUs would enable us to target resources more effectively in practice.

As prone positioning is likely to become frequent in ICUs during the coming months, this article hopes to inform clinicians and nurses of the main risk factors for the development of PUs. The aim of this study was to identify risk factors independently predictive of PUs in adult patient populations treated by PP, to estimate the prevalence of PUs, and evaluate a possible epidemiological association between the prevalence of PUs and specific clinical characteristics so as to develop clinical indicators for the prevention of PUs. Our secondary aim was to examine our study participants against the incidence of PUs with respect to the length of their stay.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This retrospective study enrolled patients hospitalized during the period of May 2020 to January 2021, Data was collected from 299 patients hospitalized and having required prone positioning ventilatory therapy in critical care areas (short-stay units, emergency units, and intensive care units). The main variables captured included the development of a PU of at least grade two according to the classification system proposed by the NPUAP/EPUAP, the service in which the patient was admitted, the month during which the hospitalization took place, the patient’s sex, age, and BMI, a history of smoking, the presence of diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, the days of the patient’s hospital and CCA stay, and the state of the patient’s life. Finally, the aim was to assess the inflammatory state of the patients. Acute phase reactant values at the beginning of hospitalization and the highest value recorded were captured, including PCR, DHL, CPK, ferritin, D-dimer, and fibrinogen.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

Data wrangling and statistical analyses were performed by R, version 4.0.3, with the use of the following packages: tidyverse, readxl, performance, gtools, MASS, bootStepAIC, lmtest, and car. Descriptive statistics were obtained with tableone:: CreateContTable | CreateCatTable and quantile values were obtained with stats:: quantile for the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles. Residuals were tested for normality with stats:: shapiro.test.

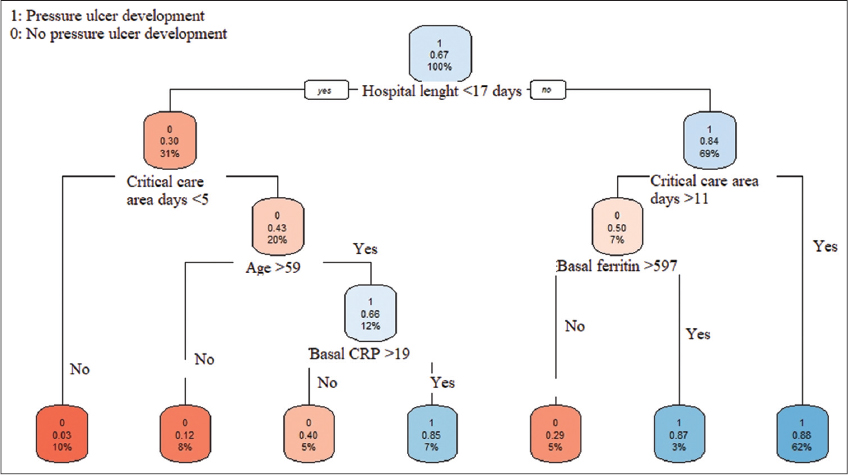

As the first step for identifying which factors are associated with PUs, we grew random classification trees with rpart:: rpart with default values for categorical outcomes. Results suggested that the optimal cut-off for hospitalization length was seventeen days. A variable “long hospitalization=TRUE/FALSE” if hospitalization length > 17 days was created with dplyr:: mutate.

Afterward, we ran multivariable linear models with stats:: glm. Subsequently, we evaluated the relevance of potential predictors by analyzing their contribution to the explanatory capacity of the model (AIC), the consistency of their coefficient signs, and the consistency of their statistical relevance. This was done via a bootstrap AIC consistency diagnosis, in which a hundred independent samples were drawn at random from the dataset with bootStepAIC:: boot.stepAIC. Model assumptions were evaluated with performance:: check_model. Statistical plots were built with ggstatsplot:: ggbetweenstats, and APA standard statistical reports were employed with their default parameters.

Due to the descriptive nature of our study, no outcome-based sample size was considered. In a post hoc calculation, we had power to detect f2 differences as small as 0.05, with an alpha of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.8 in linear multiple regressions with as a many as three predictors; and to detect R2 as low as 0.1 with ORs above 2.0, assuming the same statistical error parameters. Nonetheless, interaction terms were avoided and no more than three predictors were evaluated in each linear model. Statistical power and sample size assessments were performed with G*Power, version 3.1.9.4.

Raw Data and Analysis Code Availability

Anonymized raw data from the web survey and the step-by-step, commented code used for wrangling and analysis are publicly available at https://github.com/AdrianSotoM/PU.

Ethics Statement

The realization of this study was approved by the ethics committee of the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán.” All photographs of the patients with severe cutaneous affection during their stay in the ICU were published with their approval or one of its proxies. The patients in this manuscript gave written informed consent to the publication of their case details.

RESULTS

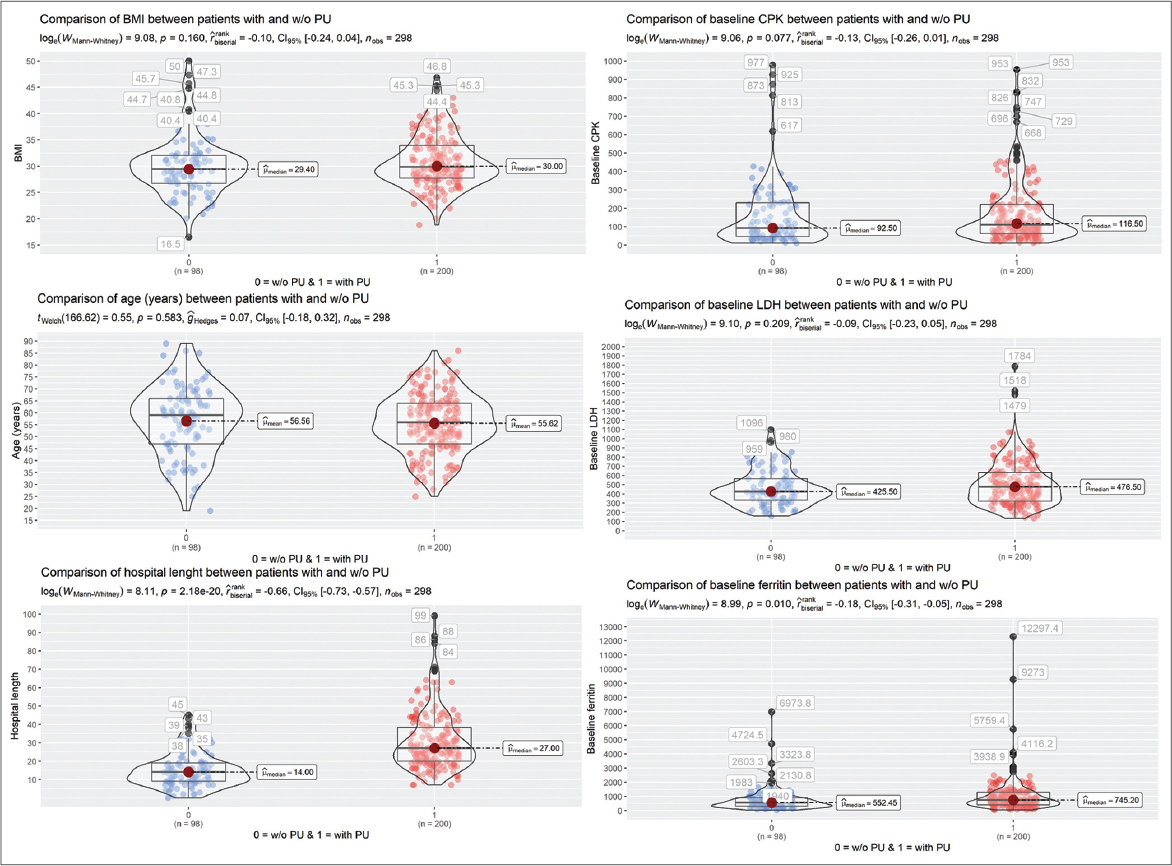

Figures 1 and 2 summarize data analysis.

Factors Associated with the Development of PUs

We found a significant association between hospital stay lengths above seventeen days and the development of PUs. Other characteristics that showed a correlation with PU development were a critical care area stay longer than eleven days, basal ferritin > 597 mg/L, and basal C-reactive protein > 19 mg/L.

Patients who developed PUs at the end of their stay in a CCA were compared with patients who did not develop PUs during their stay in a CCA. Patients from the former group were mostly males; also, they presented with higher initial levels of CPK and ferritin on their laboratory studies. A significant relationship between the development of PUs and the length of the stay in a CCA was found; additionally, patients who had developed PUs had a longer hospitalization stay overall and were more prone to die. The behavior of acute phase reactants during follow-up showed the highest level recorded during their hospital stay of CPK, ferritin, and fibrinogen among patients who had developed a PU when compared to those who had not. All patients required sedatives and anesthetics, including fentanyl, midazolam, propofol, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, vecuronium, and cisatracurium. All patients required norepinephrine with a maximum dose of 0.99 mg/kg/min, with a median of 0.19 mg/kg/min.

DISCUSSION

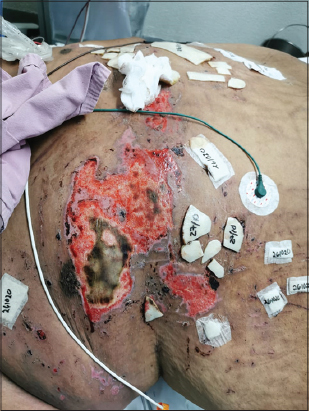

PUs in the context of prone positioning ventilatory therapy have become a major problem in intensive care units worldwide. They may be of a huge extent and depth and compromise the health and recovery of the patient (Fig. 3). We are still in the middle of the pandemic and it does not seem to be ending any time soon [8]. We assessed the prevalence of PUs and explored their association with specific clinical characteristics among patients. Our data analysis revealed that prolonged hospitalization is, by far, the most important risk factor associated with developing PUs. Importantly, pressure ulcers could be explained by the length of hospital stay alone, as other previously reported risk factors such as diabetes and a high BMI lost significance after adjusting for hospitalization length.

|

Figure 3: Pressure ulcer related to prone positioning in a COVID-19 patient. |

In agreement with our finding, a study conducted in Greece [6] also found that the length of stay was the most significant predictor of developing PUs, similarly to a study in Saudi Arabia [9] showing that the length of stay and advanced age were the most significant predictors for PUs. Among the limitations of this study is the fact that the overall incidence of PUs (84.2%) is extremely high, which leaves a small group without the outcome as to observe differences; also, determinations were made in a single facility, which could have limited the external validity of the study.

Even if hospitalization length is a well-known risk factor for PUs, these results yield insight into anticipating these complications and are unique for prone-positioned patients. Keeping in mind that prone positioning has proven beneficial even for non-intubated COVID-19 patients [10], it is reasonable to expect an increase in the incidence of these complications.

PUs have proven to be inconstantly associated with a myriad of risk factors. While some studies [11] have put forward prediction tools for identifying risk factors such as age, sex, BMI, and comorbidities such as diabetes [12] or obesity, others have not found good predictors for these complications [7]. Anticipating this, we evaluated both adjusted and unadjusted models with AIC directed bootstrap and corroborated the inconsistency of these factors with the exception of hospital length.

As hospital length is a well-discussed risk factor and probably the only one well established for the development of PUs, it is important to highlight that hospital length is, in many cases, a non-modifiable factor and an unknowable factor. The interactions and point of care taken to the patient receive the most attention regarding PU development. The Braden scale evaluates the possibility of developing PUs, being accurate in 50% [13]. The real factors intervening are the individualized decisions taken by the multidisciplinary team (nurses, physicians, primary caregivers, etc.) to establish prevention strategies, which, when applied, may become the most important modifiable factors in the development of PUs [14,15].

On the other hand, and as our data correlates, using acute phase reactants as predictors factors or docking them into a prediction tool does not show an adequate predicting value [11]. Possibly because of the intrinsic nature of PUs, ideally, these should not happen. Therefore, it was difficult to establish a linear relation regarding attempts to employ inflammation markers [16] to estimate the potential for PU development.

Notoriously, the widely used Braden scale for assessing the risk of developing PUs does not consider hospital length and has shown to be more predictive after 72 hours [17]. While this discrepancy could be explained by a different clinical context in our study (involving only COVID-19 patients), our results highlight the importance of identifying context-specific predictors or refining their definition cut-offs for anticipating these complications and, potentially, avoiding them.

The design and data of our study are not enough to develop prediction tools, yet highlight the need for considering other overlooked factors, such as hospitalization length, and for identifying context-specific risk factors[18].

CONCLUSION

This study has shared valuable information on the most important risk factors in the development of PUs due to prone positioning. We have described how the total number of days of hospitalization are significantly related to the development of PUs. Although PUs are not life-threatening lesions, the implementation of improved positioning protocols may enhance results in critical patient care. We believe that this is a current, globally underestimated problem as the incidence of COVID-19 patients requiring prone positioning—and, therefore, at risk for PUs—is increasing daily. We also emphasize the establishment of individualized prevention strategies in the context of a multidisciplinary team. We hope that the results of our effort are able to heighten the awareness about and improve the prevention of PUs due to PP, so that patients who survive COVID-19 may live without these preventable sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to give special thanks to the nurses in the Wound and Ostomy Clinic at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán” involved in the assessment and record-keeping of the patients with pressure ulcers hospitalized in critical care areas. All authors revised the manuscript and provided critical feedback. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Lasek J, Brzeziński P. Trauma and COVID-19 infection. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12:e96.

2. Ganjoo S, Vasani R, Gupta T. Urticarial eruption in COVID-19-positive children:A report of two cases. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13:47-9.

3. Abreu Velez AM, Thomason AB, Jackson BL, Howard MS. Recurrent herpes zoster with IgD deposits, multinucleated keratinocytes and overexpression of galectin and glypican 3 in a patient with SARS-COVID-19 infection. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13:41-4.

4. Kaur T, Kaur S. A multi.center, cross.sectional study on the prevalence of facial dermatoses induced by mask use in the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13:1-5.

5. Moore Z, Patton D, Avsar P, McEvoy NL, Curley G, Budri A, et al. Prevention of pressure ulcers among individuals cared for in the prone position:Lessons for the COVID-19 emergency. J Wound Care. 2020;29:312-20.

6. Tsaras K, Chatzi M, Kleisiaris CF, Fradelos EC, Kourkouta L, Papathanasiou IV. Pressure ulcers:Developing clinical indicators in evidence-based practice. A Prospective Study. Med Arch. 2016;70:379-83.

7. Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson EA, Closs SJ, Defloor T, Halfens R, et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development:Systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:974-1003.

8. Nishi N, Sonappa UK, Rajashekar TS, Hanumanthayya K, Kuppuswamy SK. A pilot study assessing the various dermatoses associated with the use of a face mask during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12:349-53.

9. Tayyib N, Coyer F, Lewis P. Saudi Arabian adult intensive care unit pressure ulcer incidence and risk factors:A prospective cohort study. Int Wound J. 2016;13:912-9.

10. Perez-Nieto OR, Escarraman-Martinez D, Guerrero-Gutierrez MA, Zamarron-Lopez EI, Mancilla-Galindo J, Kammar-García A, et al;APRONOX group. Awake prone positioning and oxygen therapy in patients with COVID-19:The APRONOX study. Eur Respir J. 2021:2100265.

11. Aloweni F, Ang SY, Fook-Chong S, Agus N, Yong P, Goh MM, et al. A prediction tool for hospital-acquired pressure ulcers among surgical patients:Surgical pressure ulcer risk score. Int Wound J. 2019;16:164-75.

12. Børsting TE, Tvedt CR, Skogestad IJ, Granheim TI, Gay CL, Lerdal A. Prevalence of pressure ulcer and associated risk factors in middle- and older-aged medical inpatients in Norway. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:e535-43.

13. Tescher AN, Branda ME, Byrne TJ, Naessens JM. All at-risk patients are not created equal:analysis of Braden pressure ulcer risk scores to identify specific risks. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39:282-91.

14. Olshansky K. Predicting the development of pressure ulcers and the 'ostrich syndrome’. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39:474-5;author reply 477.

15. Gadd MM. Preventing hospital-acquired pressure ulcers:Improving quality of outcomes by placing emphasis on the Braden subscale scores. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39:292-4.

16. Perier C, Granouillet R, Chamson A, Gonthier R, Frey J. Nutritional markers, acute phase reactants and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 in elderly patients with pressure sores. Gerontology. 2002;48:298-301.

17. Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M, Champagne M, Ruby E. Predicting pressure ulcer risk:A multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale. Nurs Res. 1998;47:261-9.

18. Marin J, Nixon J, Gorecki C. A systematic review of risk factors for the development and recurrence of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:522-7.

Notes

Source of Support: We receive no support for this study

Conflict of Interest: We have no conflict of interest

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4923-8880 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4923-8880 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3542-4615 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3542-4615 |

Comments are closed.