Effects of plaster therapy on thigh fat

Clínica Áurea – Aesthetic Biomedicine Clinic; Rua de Três Lagares, bloco 1, loja G, 5000-577 Vila Real, Portugal

Corresponding author: Sara Gonçalves, MSc

How to cite this article: Gonçalves S. Effects of plaster therapy on thigh fat. Our Dermatol Online. 2022;13(1):32-35.

Submission: 08.07.2021; Acceptance: 16.10.2021

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20221.6

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2022. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Thigh fat is associated with high cardiometabolic risks, attenuate risk for dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance. Aerobic exercise has been linked to fat metabolization due to the increase of free fatty acid oxidation and the preservation of muscle glycogen. Plaster therapy, a beauty treatment that allows the quick elimination or reduction of cellulite, flaccid skin, and localized fat, eliminating liquid from the body, producing improvements that are not only aesthetic but also health-wise, may be used to maximize fat loss in the thigh area and complement exercise. The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of plaster therapy in combination with aerobic exercise on thigh fat.

Methods: Six female volunteers were randomly divided into an intervention group (TG; n = 3) performing an aerobic exercise with plaster therapy and a control group (CG; n = 3) performing only aerobic exercise. Subcutaneous fat was estimated by the analysis of skinfolds and thigh perimeters.

Results: The treatment group demonstrated a significant decrease (p ≤ 0.05) in subcutaneous fat at the left and right perimeters and thigh skinfold measurements at the end of the 10-session protocol.

Conclusion: Comparing skinfold measurements, both groups revealed a statistically significant decrease in the perimeter of both left and right thighs. Furthermore, skinfold measurements showed, for the treatment groups, significant statistical results in the thigh area. Exercise is indeed one of the most critical components for the metabolism of fat. Plaster therapy in combination with aerobic exercise seems to be effective for thigh fat reduction.

Key words: Clay; Physical Exercise; Plaster Therapy; Thighs

INTRODUCTION

Thigh fat is associated with high cardiometabolic risks, attenuate risk for dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance [1–3].

Aerobic exercise has been linked to fat metabolization due to the increase of free fatty acid oxidation and the preservation of muscle glycogen [4]. Plaster therapy, a beauty treatment that allows the quick elimination or reduction of cellulite, flaccid skin, and localized fat, eliminating liquid from the body, producing improvements that are not only aesthetic but also health-wise [1], may be used to maximize fat loss in the thigh area and complement exercise.

In practice, the procedure begins with the preparation of the skin. During this process, the area is cleansed and exfoliated to better absorb the ingredients. Lemon essential oil has a diuretic effect and is used in obese patients at a dilution of 3% [5,6].

During the treatment, the plaster absorbs heat released by the body, which increases blood circulation and facilitates the penetration of the active ingredients into the skin [7,8]. Green clay is used to complement the treatment since it contains minerals such as iron and magnesium, facilitating lipolysis [9]. Iron increases the rate of lipolysis in adipocytes [10].

The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of plaster therapy in combination with aerobic exercise on thigh fat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The controlled trial sample was composed of six female volunteers selected through a questionnaire and divided randomly into treatment (TG; n = 3) and control (CG; n = 3) groups. Volunteers were selected with a body mass index (BMI) falling between 18.5 and 29.9, corresponding to the normal range and pre-obese [11]. Excluded from the sample were those who practiced regular physical activity, had a disease or risk factor that might have influenced lipid metabolism, had one or more contraindications to the treatment, or regularly smoked or consumed alcohol.

Instruments

A nonstretchable measuring tape (170750 lot, Comed, France) was employed to measure height and perimeters. Bioelectrical impedance Tanita UM-076 was employed to register weight. Skinfolds were determined with Digital Skinfold Analyzer (170125 lot, Comed, France). An automatic arm sphygmomanometer (BM26, Beurer Medical, Germany) was used to measure heart rate at rest.

A preparation of sweet almond oil (TulsiCosmetics Professional, Portugal) and lemon essential oil (Citrus Limon, Plena Natura, Portugal) was used for dynamic massage. Plaster therapy was prepared with the following components: magnesium sulfate (19998901 lot, Labchem, Portugal), distilled water, a plaster bandage (MedicalExpress, Portugal), and green clay (712644 lot, Cattier Paris, France). Aerobic exercise was performed on an exercise bike (EB 120 DOMYOS).

Procedures

Two sessions were performed per week with a duration of five weeks. Assessments were done before (M0) and after (M1) each of the ten sessions. Height and weight were measured. The perimeter was measured for the thighs (the volunteers were asked to stand up, and the measurement was performed just below the gluteal fold) [12]. Skinfolds were measured at the triceps, suprailia, and thigh areas [12,13].

The percentage of body fat was estimated with skinfold measures according to the following formula: z

body density = 1.0994921 − (0.0009929 × (X1)) + (0.0000023 × (X1)) × 2 − (0.0001392 × age)

body fat (%) = 495 ÷ body density − 450

where X1 is the sum of triceps, suprailia, and thigh skinfolds in millimeters [12].

The TG intervention protocol began with a five-minute dynamic massage on each thigh to promote blood circulation with 20 ml of sweet almond oil and 12 drops of lemon essential oil. Then, a solution of 50 g of green clay combined with 25 g of magnesium sulfate in 30 ml of distilled water was applied on the thighs to improve clay element mobility. The plaster bandage was impregnated with 10 g of magnesium sulfate in 0.5 L of water and then applied. Finally, a plastic film was applied around the plaster bandage to keep it moist and retain body temperature.

While using the plaster bandage, participants performed thirty minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on an exercise bike, monitored with Polar heart monitors on the bike and a Borg scale. The exercise was performed with Karvonen’s formula, at 50% of the heart rate reserve (HR):

HRreserve = (220 − age) − HRresting

HRduring training = HRresting + (0.50 × HRreserve)

The CG only performed aerobic exercise following the same criteria as the TG. A physical therapist performed all these procedures from the clinic.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26, USA), with a significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05). Given the small sample size, non-parametric tests were applied. All severe outliers were excluded from the sample (n = 1).

A new variable was calculated using differences between the final and initial values in each group. A Mann–Whitney test was applied to compare the groups, and a Wilcoxon test allowed comparison between the initial and final measures in each group.

Ethics Statement

All volunteers signed informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

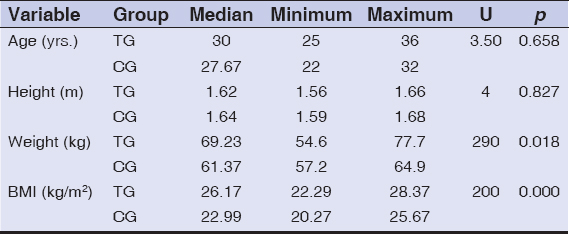

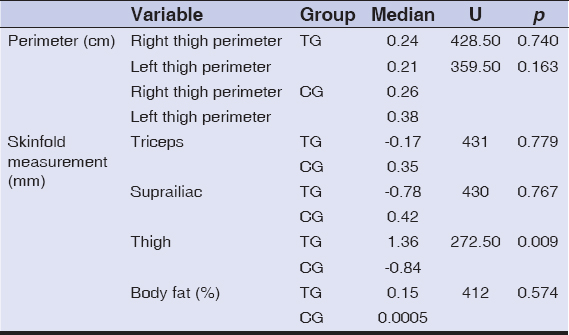

The sample (n = 6) was characterized as shown in Table 1, and no significant differences were found between groups, making them comparable. A significant decrease was found in thigh skinfold measurement (Table 2).

Considering that two statistically significant results were observed in 25 variables, it was essential to analyze variable behavior in each group after ten sessions (Table 3). In the TG skinfold measurements, a significant decrease in subcutaneous fat on the thigh skinfold was observed. TG perimeter measures decreased on the right and left thighs. The CG also revealed significant statistical results, namely reducing subcutaneous on the right and left thighs.

DISCUSSION

While analyzing the results of the study, it was possible to verify a significant decrease in thigh fat in the TG when compared with the CG, confirmed by the perimeter and skinfold measurements of the thigh. With a larger sample, a higher number of significant statistical results could probably have been observed. However, since restricted inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted, this was not possible. These results reinforce the notion that a plaster body wrap produces a positive action on reducing thigh fat.

Considering the results of the study, it seems that plaster therapy may enhance the reduction in thigh perimeter. It should, however, complement physical exercise and an optimal diet [14,15]. When comparing skinfold measurements, both groups revealed a statistically significant decrease in the perimeter of both left and right thighs. Furthermore, skinfold measurements showed, for the treatment groups, significant statistical results in the thigh area. Exercise is indeed one of the most critical components for the metabolism of fat.

Concerning lemon essential oil, Price and Price [5] refer to its use as a diuretic and obese people. However, there is a lack of studies on applying lemon essential oil in adipose tissue after its application on the skin. According to Tisserand and Young [6], lemon essential oil is phototoxic, and the skin should not be exposed to the sun in the next twelve hours after its topical application. None of the patients reported any adverse effects to the compounds used to perform plaster therapy. This therapy seems to present no risks to health with the quantities and periods analyzed.

CONCLUSION

While analyzing the results of the study, it was possible to verify a significant decrease in thigh fat in the TG when compared with the CG, confirmed by the perimeter and skinfold measurements of the thigh. With a larger sample, a higher number of significant statistical results could probably have been observed. However, since restricted inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted, this was not possible. These results reinforce the notion that a plaster body wrap produces a positive action on reducing thigh fat. Plaster therapy may function as an adjunct to physical exercise in reducing thigh fat. Therefore, it is essential to highlight the results of this study so that aesthetic biomedicine professionals and physical therapists consider this novel tool for lipolysis enhancement [14].

It is also essential to perform a correct assessment of all measures, which should always be performed by the same professional to avoid minor mistakes and miscalculations [16].

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Eastwood SV, Tillin T, Wright A, Mayet J, Godsland I, Forouhi NG, et al. Thigh fat and muscle each contribute to excess cardiometabolic risk in South Asians, independent of visceral adipose tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:2071-9.

2. Ebbert J, Jensen M. Fat depots, Free fatty acids, and dyslipidemia. Nutrients. 2013;5:498-508.

3. Baldisserotto M, Damiani D, Cominato L, Franco R, Lazaretti A, Camargo P, et al. Subcutaneous fat:A better marker than visceral fat for insulin resistance in obese adolescents. E-SPEN J. 2013;8:e251-5.

4. Knuiman P, Hopman MTE, Mensink M. Glycogen availability and skeletal muscle adaptations with endurance and resistance exercise. Nutr Metab. 2015;12:59.

5. Zielinski E. The healing Power of Essential Oils. First. New York:Harmony Books;2020.

6. Tisserand R, Young R. Essential Oil Safety – A Guide for Health Care Professionals. Second. Elsevier;2014.

7. Seeley R, VanPutte C, Regan J, Russo A. Seeley’s Anatomy &Physiology. 10th ed. United States of America:McGraw Hill;2014.

8. ZsikóS, Csányi E, Kovács A, Budai-Szűcs M, Gácsi A, BerkóA. Methods to evaluate skin penetration in vitro. Sci Pharm. 2019;87:19.

9. Buriti BMAB, Buriti JS, Silva IA, Cartaxo JM, Neves GA, Ferreira HC. Characterization of clays from the State of Paraíba, Brazil for aesthetic and medicinal use. Cerâmica. 2019;65:78–84.

10. Santos Moreira J, Melo ASCP de, Noites A, Couto MF, Melo CA de, Adubeiro NCF de A. Plaster body wrap:effects on abdominal fat. Integr Med Res. 2013;2:151-6.

11. Nuttall FQ. Body Mass Index:Obesity, BMI, and Health. Nutr Today. 2015;50:117-28.

12. Mussoi TD. Avaliação Nutricional na Prática Clínica:da gestação ao envelhecimento. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro:Guanabara Koogan;2014.

13. Norton KI. Standards for Anthropometry Assessment. In:Norton K, Eston R, editors. Kinanthropometry Exerc. Physiol. 4th ed., Fourth Edition. |New York:Routledge, 2018. |Roger G. Eston Is the Principal Editor of the Third Edition Published 2009. |“First Edition Published by Routledge 2001“—T.p. Verso.:Routledge;2018, 68-137.

14. Gonçalves S. Elaboration and subsequent application of a protocol for measure reduction in a patient with Hashimoto thyroiditis. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:243-6.

15. Gonçalves S. Sculpt plaster therapy for abdominal circumference reduction. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12:79-81.

16. Gonçalves S. A Consulta de Biomedicina Estética. vol. 1. 1st ed. Portugal:escrytos;2021.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8287-1357 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8287-1357 |

Comments are closed.