An unusual case of nasal chromoblastomycosis degenerating into squamous cell carcinoma from a nonendemic region

Refka Frioui 1, Kahena Jaber1, Latifa Mtibaa2, Bouthaina Jamli2, Faten Grgouri3, Faten Rabhi1, Abderraouf Dhaoui1

1, Kahena Jaber1, Latifa Mtibaa2, Bouthaina Jamli2, Faten Grgouri3, Faten Rabhi1, Abderraouf Dhaoui1

1Department of Dermatology, Military Hospital of Tunis, 1008, Monfleury, Tunis, Tunisia, 2Laboratory of Parasitology-Mycology, Military Hospital of Tunis, 1008, Monfleury, Tunis, Tunisia, 3Department of Pathology, Military Hospital of Tunis, 1008, Monfleury, Tunis, Tunisia

Corresponding author: Refka Frioui, MD

How to cite this article: Frioui R, Jaber K, Mtibaa L, Jamli B, Grgouri F, Rabhi F, Dhaoui A. An unusual case of nasal chromoblastomycosis degenerating into squamous cell carcinoma from a nonendemic region. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12(4):422-426.

Submission: 23.09.2020; Acceptance: 24.11.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20214.16

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2021. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM) is a granulomatous mycosis rarely described outside tropical countries. Degeneration into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is its most serious complication. We report the first case of nasal CBM degenerating into SCC. In 2006, a sixty-year-old male presented himself with an infiltrated plaque on the right thigh. The diagnosis of CBM was confirmed by the presence of fungal elements. In 2019, the patient had developed a mass coming from the right nasal cavity. It had rapidly involved the nasal dorsum. An ulcer-budding nasal tumor and an elevated erythematous and verrucous plaque on the thigh were noted. A biopsy revealed a granulomatous dermis with fungal elements. Other nasal biopsy fragments showed differentiated SCC. A fungal culture inoculated with tissue from both lesions showed dark colonies. The diagnosis of nasal CBM with SCC degeneration was reached. The patient presented asymptomatic endonasal CBM that had slowly evolved and recently degenerated.

Key words: Chromoblastomycosis; Nose; Squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Chromoblastomycosis (CBM) is a slowly progressive granulomatous mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by inoculation of dematiaceous fungi mainly on the lower limbs. This infection occurs in tropical and subtropical regions, but there have been several case reports from temperate regions. If not diagnosed and treated at an early stage, it may rarely undergo malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which is its most serious complication [1]. Herein, we report an unusual case of CBM from Tunisia, a nonendemic area, occurring in a distant site from the original lesion and degenerating into SCC.

CASE REPORT

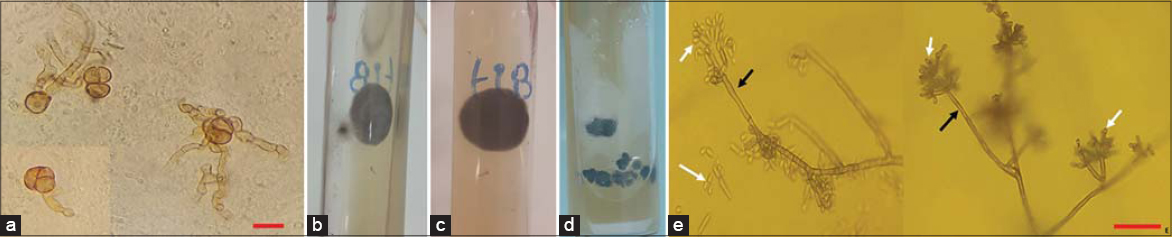

In 2006, a sixty-year-old healthy male from north Tunisia presented himself to our dermatology department with an infiltrated 6 × 5 cm erythematous plaque on the right thigh. A histopathological examination revealed the presence of fungal elements. A mycologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of CBM, but the species was not identified. On interrogation, the patient reported no travels to tropical areas, but worked as a masseur in a Turkish bath in conditions of high humidity and heat. The patient also remembered having been injured in this site two years ago at work. The patient was treated with terbinafine at a dose of 500 mg/day. There was a significant decrease in the size of the lesion, but he was lost to follow-up after three months. Several years later, he developed a fleshy reddish mass coming from the right nasal cavity with mucopurulent discharge. Over the last three months, it had rapidly extended and involved the nasal dorsum. An examination revealed a bleeding 4 × 3 cm ulcer-budding nasal tumor with an irregular edge surmounted by telangiectasias (Fig. 1). Dermoscopy revealed a vascular pattern with polymorphous vessels. No cervical lymph nodes were palpable. On the right thigh, we found a 12 × 13 cm slightly elevated pruritic erythematous and verrucous plaque with atrophy and depigmentation in most places (Fig. 2). The rest of the examination was normal. There was no evidence of immunodeficiency. Clinically, the differential diagnoses of the tumor form of CBM and SCC were considered. Biopsies were taken from several sites of the nasal lesion and the plaque on the thigh. Histopathology revealed the presence of fungal elements in a granulomatous reaction and mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figs. 3a and 3b). Other endonasal and nasal dorsum biopsy fragments showed moderately differentiated SCC (Fig. 3c). A direct microscopic examination showed fumagoid cells (Fig. 4a). Fungal cultures of the two samples on Sabouraud dextrose agar showed a growth of pigmented, velvety-dark colonies (Figs. 4b – 4d). A microscopic examination of the colonies revealed cylindrical septate hyphae, and conidiophores swollen at their termination carrying ovoid conidia suggestive of the Fonsecaea pedrosoi species (Fig. 4e). From these features, the diagnosis of nasal CBM with SCC degeneration was reached. A neck-chest-abdomen CT scan was normal. We started a combined therapy consisting of terbinafine at 500 mg and itraconazole at 200 mg daily, and referred the patient to the oncosurgery department.

DISCUSSION

CBM is one of the most prevalent transcutaneous traumatic implantations in individuals living in tropical and subtropical climate areas of America, Asia, and Africa [2]. However, sporadic cases are being increasingly more often described in temperate zones, such as Western Europe and North Africa. In Maghreb countries, and particularly in Tunisia, CBM has been rarely reported: so far five cases have been published [3]. All etiological agents of CBM are black fungi with low pathogenicity thermosensitive at 40–42oC and living as saprophytes in the soil, plants, thorns, debris, and transported wood. They have also been isolated in saunas, where the conditions of high humidity and heat create a tropical microclimate that might explain the development of fungi even in temperate areas [4]. This is probably the case in our patient, who worked as a masseur in a Turkish bath.

The typical lesions usually tend to be found in exposed and nonprotected areas of the body, especially the feet and legs. According to Minotto R et al., 27% of cases involve other areas, including the medial canthus of the eye, the ears, neck, shoulder, chest, wrists, and buttocks [5]. The nasal cavity is rarely affected by CBM and there have been only a few such cases described [6]. Our patient’s first lesion occurred unusually in an unexposed location—the inner part of a thigh—which might also be explained by his professional occupation. In general, CBM is a localized infection invading body sites in the immediate area of the original lesions, but usually without metastasis to distant sites. The site of our patient’s second lesion might have been explained by autoinoculation due to itching.

CBM has diverse clinical aspects, including nodular, verrucous, tumoral, plaque-like, and psoriasiform appearances. Cicatricial atrophy with central sparing may also be seen. Because of this clinical polymorphism, CBM may be confused in our country with leishmaniasis, verrucous tuberculosis, and tertiary syphilis. A positive diagnosis is usually confirmed by characteristic mycological and histopathological results. When skin biopsies or scrapings are examined under microscopy, pathognomonic muriform cells are seen. These rounded, cigar-colored, and cross-chambered structures are distinctive, and are also known as Medlar bodies, sclerotic bodies, and fumagoid cells [8]. Histologically, CBM typically reveals a dermal granulomatous infiltrate with a predominance of epithelioid cells surrounding fumagoid bodies [7]. A culture allows the isolation and identification of the causal organisms in about fifteen days. Initially, colonies are deep-green, depicting a dark velvet aspect with time. Presumptive species identification may be achieved by mycological morphologic methods, but molecular techniques are suggested for definitive identification.

CBM lesions are usually recalcitrant and extremely difficult to eradicate. If not diagnosed and treated early, CBM has a chronic evolutional course with numerous complications, such as secondary bacterial infection, lymphoedema, and chronic nonhealing ulcers.

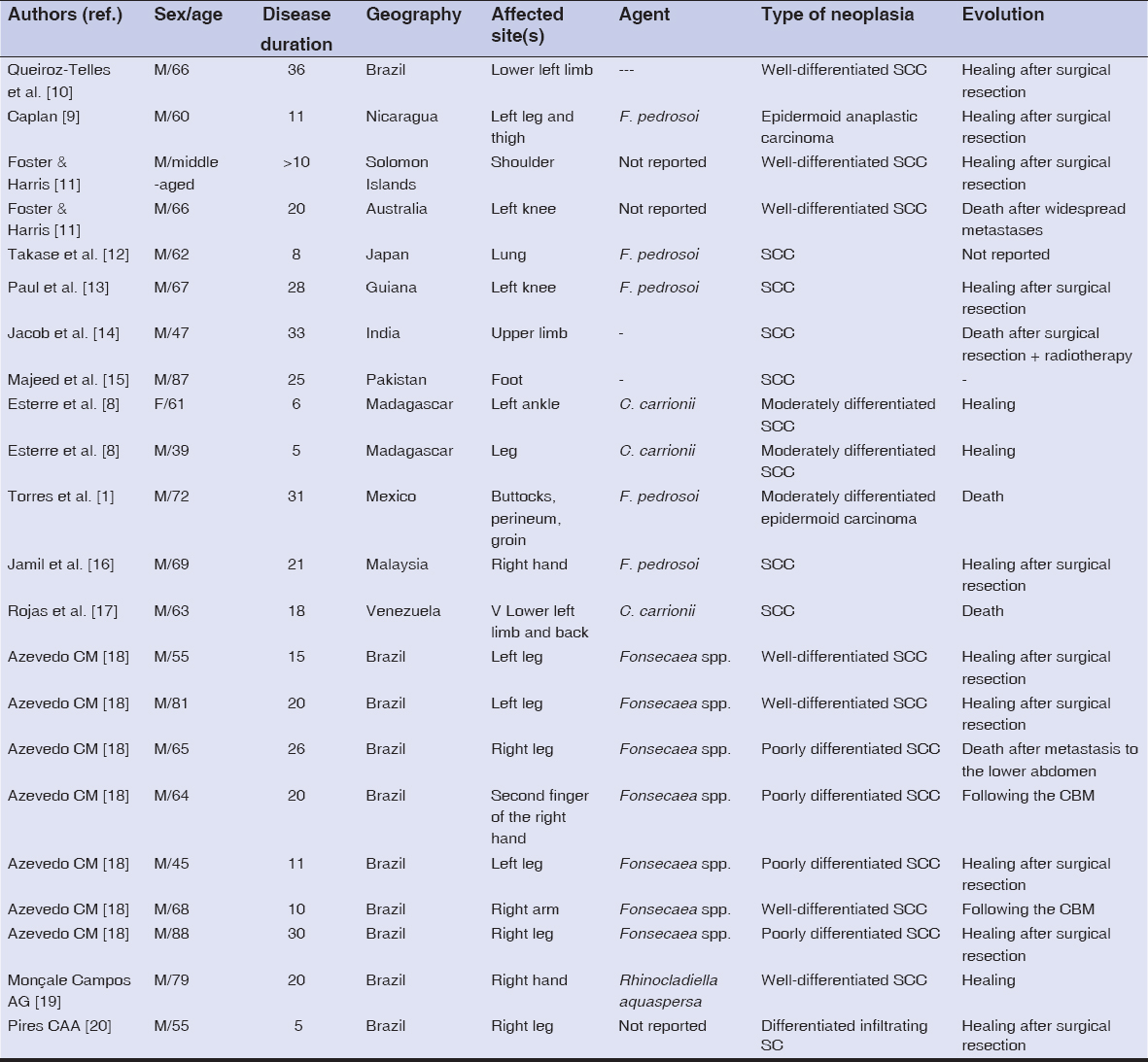

The major risk is malignant transformation mainly into SCC [1]. The risk of malignant transformation is around 1%, as illustrated in a Madagascar study in which neoplasia was reported in 14 out of 1400 cases over a period of fifty years [8]. The first reported case of malignant degeneration was described by Caplan in 1968 in a patient from Nicaragua presenting with verrucous plaque lesions on the legs, left thigh, and right hand, which evolved over a period of approx. eleven years [9]. Subsequently, around 23 cases of tumors derived from CBM were documented worldwide (Table 1) [9–20]. The sex ratio was 19/2. The average disease evolution time was 19.7 years. The main affected site was the lower limbs. Cases of CBM-derived SCC were, in the majority, cured after surgical excision.

|

Table 1: A summary of reported cases of chromoblastomycosis with malignant transformation |

CONCLUSION

Malignancy must be suspected in the case of any suspicious change, such as the development of ulceration, a rapid growth, or a poor response to treatment. Without a doubt, the conditions of the affected tissue, which involve inflammation and chronic reparatory processes, are significant predisposing factors. Our patient had endonasal CBM that had slowly and asymptomatically evolved and had recently degenerated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the patient.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Torres E, Beristain JG, Lievanos Z, Arenas R. Chromoblastomycosis associated with a lethal squamous cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:267-70.

2. Gomes RR, Vicente VA, Azevedo CM, Salgado CG, da Silva MB, Queiroz-Telles F, et al. Molecular epidemiology of agents of human chromoblastomycosis in brazil with the description of two novel species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0005102.

3. Chaabane H, Mseddi M, Charfi S, Chaari I, Boudawara T, Turki H. [Chromoblastomycosis:breast solitary lesion]. Presse Med. 2015;44:842-3.

4. Pindycka-Piaszczyńska M, Krzyściak P, Piaszczyński M, Cieślik S, Januszewski K, Izdebska-Straszak G, et al. Chromoblastomycosis as an endemic disease in temperate Europe:first confirmed case and review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:391-8.

5. Minotto R, Bernardi CD, Mallmann LF, Edelweiss MI, Scroferneker ML. Chromoblastomycosis:A review of 100 cases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:585-92.

6. Shresta D, Kumar R, Durgapal P, Singh CA. Isolated nasal chromoblastomycosis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:519-21.

7. Avelar-Pires C, Simoes-Quaresma JA, Moraes-de Macedo GM, Brasil-Xavier M, Cardoso-de Brito A. Revisiting the clinical and histopathological aspects of patients with chromoblastomycosis from the Brazilian Amazon region. Arch Med Res. 2013;44:302-6.

8. Esterre P, Pecarrère JL, Raharisolo C, Huerre M. [Squamous cell carcinoma arising from chromomycosis. Report of two cases]. Ann Pathol. 1999;19:516-20.

9. Caplan RM. Epidermoid carcinoma arising in extensive chromoblastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:38-41.

10. Queiroz-Telles F, Esterre P, Perez-Blanco M, Vitale RG, Salgado CG, Bonifaz A. Chromoblastomycosis:An overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2009;47:3-15.

11. Foster HM, Harris TJ. Malignant change (squamous carcinoma) in chronic chromoblastomycosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57:775-7.

12. Takase T, Baba T, Uyeno K. Chromomycosis. A case with a widespread rash, lymph node metastasis and multiple subcutaneous nodules. Mycoses. 1988;31:343-52.

13. Paul C, Dupont B, Pialoux G, Avril MF, Pradinaud R. Chromoblastomycosis with malignant transformation and cutaneous-synovial secondary localization. The potential therapeutic role of itraconazole. J Med Vet Mycol. 1991;29:313-6.

14. Jacob M, Mathal R, Prasad PV, Bhaktaviziam A. Chromoblastomycosis with squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1988;54:314-7.

15. Majeed S, Bari AU. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in deep mycosis (chromomycosis)—a case report. J Surg Pak. 2004;9:54-5.

16. Jamil A, Lee YY, Thevarajah S. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma arising from chromoblastomycosis. Med Mycol. 2012;50:99-102.

17. Rojas OC, González GM, Moreno-Treviño M, Salas-Alanis J. Chromoblastomycosis by Cladophialophora carrionii associated with squamous cell carcinoma and review of published reports. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:153-7.

18. Azevedo CM, Marques SG, Santos DW, Silva RR, Silva NF, Santos DA, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma derived from chronic chromoblastomycosis in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1500-4.

19. Monçale Campos AG, Ezaguy de Hollanda L, Makarem Oliveira L, Francesconi do Valle F, Francesconi do Valle VA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from a chromomycosis lesion caused by Rhinocladiella aquaspersa with postsurgical recurrence of chromomycosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:915-7.

20. Pires CAA, Dias AL, Machado AKLP, de Lemos MN, Loureiro WR, Oliveira Carneiro FR. Chromomycosis:Case Reports of Exuberant Forms Including Carcinomatous Degeneration. Am J Infect Dis. 2019;15:15.23.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9441-2070 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9441-2070 |

Comments are closed.