Dermoscopy of mycosis fungoides: A study on 31 patients

Sara Elloudi 1, Samia Mrabat1, Hanane Baybay1, Zakia Douhi1, Samira El Fakir2, Fatima Zahra Mernissi1

1, Samia Mrabat1, Hanane Baybay1, Zakia Douhi1, Samira El Fakir2, Fatima Zahra Mernissi1

1Department of Dermatology, University Hospital center Hassan II,Faculty of Medecine, University Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah, Fez, Morocco, 2Department of Epidemiology and Public health, Faculty of Medicine, University Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah, Fez, Morocco

Corresponding author: Sara Elloudi, MD

How to cite this article: Elloudi S, Mrabat S, Baybay H, Douhi Z, El Fakir S, Mernissi FZ. Dermoscopy of mycosis fungoides: A study on 31 patients. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12(3):257-261.

Submission: 01.04.2021; Acceptance: 31.05.2021

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20213.5

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2021. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Its clinical presentation is highly variable, ranging from erythematous patches to plaques and nodules.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to describe the dermoscopic features of MF depending on its clinical and histological subtype.

Materials and Methods: This was a retrospective, observational study held at the Department of Dermatology and Venerology in Fez, Morocco, over a period of four years. Included were cases in which the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides was established by histopathological and immunohistochemical examination.

Results: Our results were overall in line with previous evidence. Dermoscopy of the classical form of MF is made of short linear vessels, dotted vessels, and orangish-yellow, patchy areas. In poikiloderma MF, we found mainly multiple pigmented polygonal structures, as reported in the literature.

Conclusion: We found no significant relationship between dermoscopy and histology, which might be explained by the small size of our sample. To our knowledge, this has not been described before in the literature and others studies with larger samples are necessary to determine the validity of ours results.

Key words: Mycosis fungoides; Dermoscopy; Anatomopathology; Variants of mycosis fungoides

INTRODUCTION

The clinical diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (CLD) is one of the most difficult challenges in dermatology due to their heterogeneous and protean clinical presentation [1]. Since 2009, when Moura et al. described the dermoscopic features of lymphomatoid papulosis, interest toward dermoscopy of CLD has increasingly grown, and plenty of papers have been published on the topic [2–5].

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive technique aiding in the diagnosis of both pigmented and non-pigmented skin lesions. It allows the visualization of features invisible to the naked eye. By the assessment of characteristic vascular structures, colors, and patterns, dermoscopy may improve diagnostic accuracy for several dermatologic conditions [6]. Thus, it may be regarded as an intermediate step between clinical examination and dermatopathology [7]. The aim of our study was to describe the dermoscopic features of mycosis fungoides depending on its clinical and histological subtype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective, observational study held at the Department of Dermatology and Venerology in Fez, Morocco, over a period of four years—from January 2017 through December 2020. Included were cases in which the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides was established by histopathological and immunohistochemical examination.

Clinical and dermoscopic photographs were collected from each patient, and findings were reviewed, as well as the histopathologic features from previous biopsies. The capture of the dermoscopic images was performed with a DermLite dermoscope with polarized and non-polarized light.

The variables included in the dermoscopic evaluation were the following: dotted vessels; glomerular vessels; purpuric vessels; comma vessels; fine, short, linear vessels; spermatozoa-like structures; patchy, orangish-yellow areas; white scales; multiple pigmented polygonal structures; yellow scales; and rosettes.

All variables were summarized by descriptive statistics. Qualitative variables were described in terms of proportions. Statistical analysis of the data was performed with the Epi software, version 3.4 (2007).

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees at the faculty of Medicine, University Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah in Fez, Morocco. All patients were informed of the conditions pertaining to the study and gave their written informed consent for the study and publication.

RESULTS

A total of 31 patients with MF were included. The median age was 54 years, with extremes ranging from 28 to 80 years. The male-to-female ratio was of 0.93.

The clinical presentation was dominated by macules (74%), followed by plaques (67%), papules (29%), nodules (22%), poikiloderma (22%), and tumors (9%). The classical form was the most frequent clinical form (54%). Other clinical forms included the pilotropic (19.4%) and poikilodermal form (19.4 %), hypopigmented MF (3.2%), and palmoplantar MF (3.2%).

Histological examination identified the classical MF in the majority of the patients (80.6 %), followed by pilotropic (19.4%) MF. The lymphocytic infiltrate was mainly located in the dermis (48%), followed by the epidermis (32%), and finally both the epidermis and dermis in 19.4%.

Biopsies revealed band-like lymphoid infiltrates in 64.5% of the cases, followed by Pautrier’s microabscesses (22.6%) and nodular infiltrates (12.9%).

Dermoscopic analysis of all cases found the following signs: white scales (90%), orangish-yellow areas (58%), dotted vessels (54%), short, linear vessels (42%), purpuric vessels (35%), rosettes (35%), spermatozoa-like vessels (19%), comma vessels (19%), and multiple pigmented polygonal structures (19%).

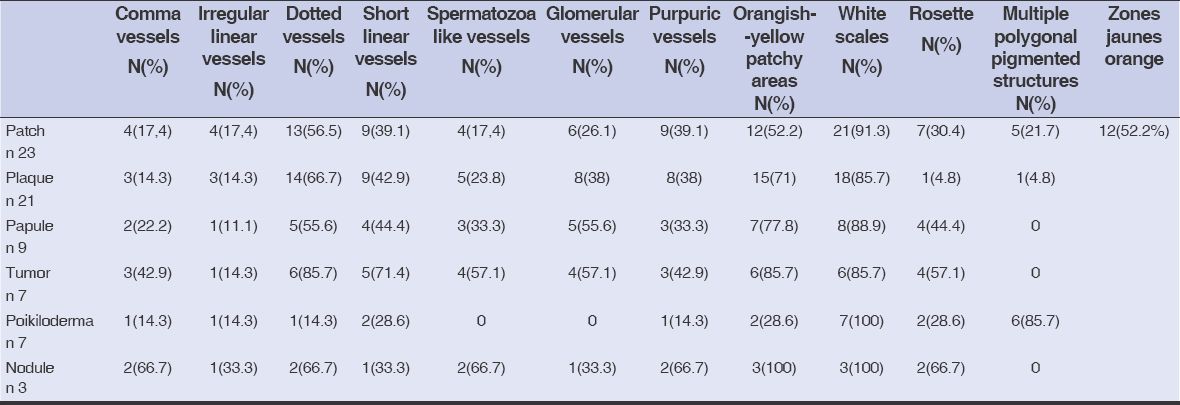

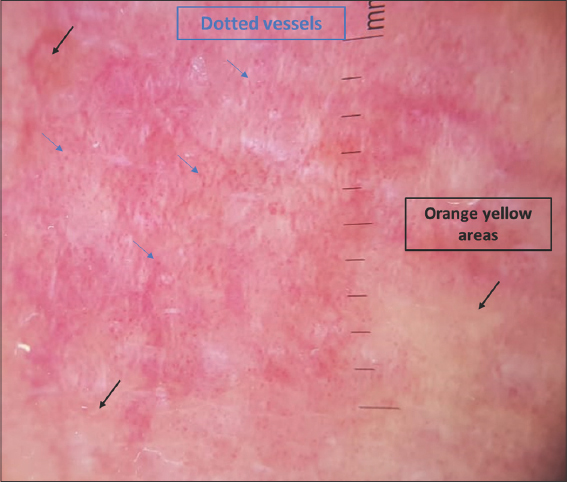

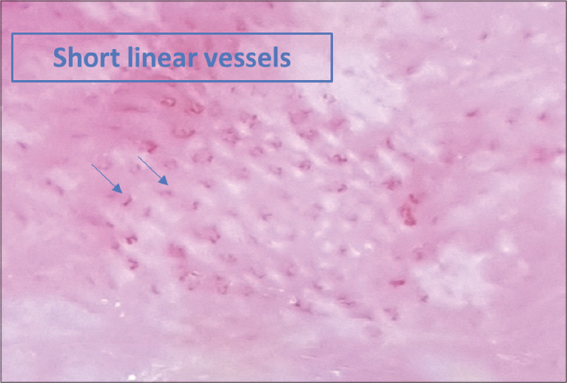

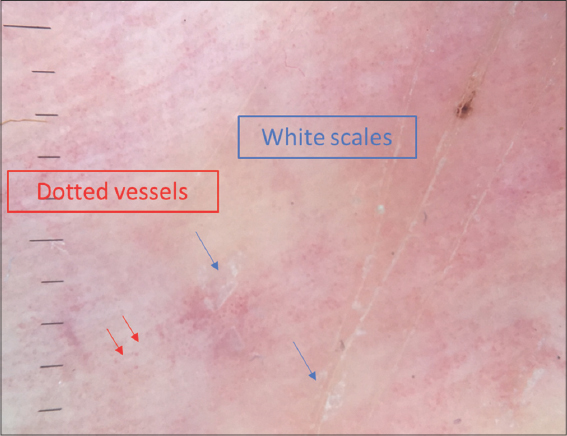

Dermoscopy signs according to the clinical presentation are shown in Table 1. Dermoscopy of the classical clinical subtype revealed the following: a vascular pattern made of dotted vessels (51%) (Fig. 1), glomerular vessels (50%), short, linear vessels (Fig. 2) (50%), purpuric vessels (28.6%), and spermatozoa-like vessels (28.6%). Other findings included orangish-yellow areas (57%) (Fig.1), white scales (78%), and rosettes (28.6%).

|

Table 1: Dermoscopic findings according to the clinical presentation |

|

Figure 1: Dermoscopy of classic plaque-stage MF showing dotted vessels (blue arrows) and orangish-yellow areas (black arrows). |

|

Figure 2: Dermoscopy of classic patch MF showing short, linear vessels. |

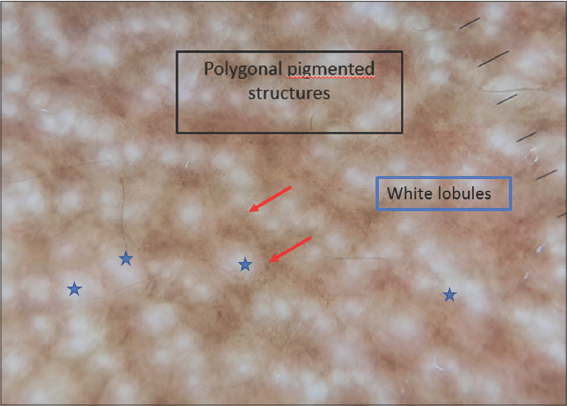

Dotted vessels, rosettes, and orangish-yellow areas were the most frequently found signs in pilotropic MF. As for poikilodermal MF, multiple pigmented polygonal structures (Fig. 3) and white scales were found in all cases (Fig. 4).

Regarding the topography of the lymphoid infiltrate, patients with dermal infiltrate presented mostly with orangish-yellow areas (64%), dotted vessels (56%), short, linear vessels (40%), and rosettes (36%). On the other hand, those with epidermal infiltrate exhibited the following signs: white scales (81%), dotted vessels (62.5%), purpuric vessels, and short linear vessels (31%).

When the lymphoid infiltrate was band-like, dermoscopy showed: white scales (95%), orangish-yellow areas (60%), dotted vessels (60%), and short, linear, and glomerular vessels (40%).

As for nodular infiltrate, we found: white scales (75%), orangish-yellow areas (75%), dotted vessels (50%), and short, linear vessels (50%).

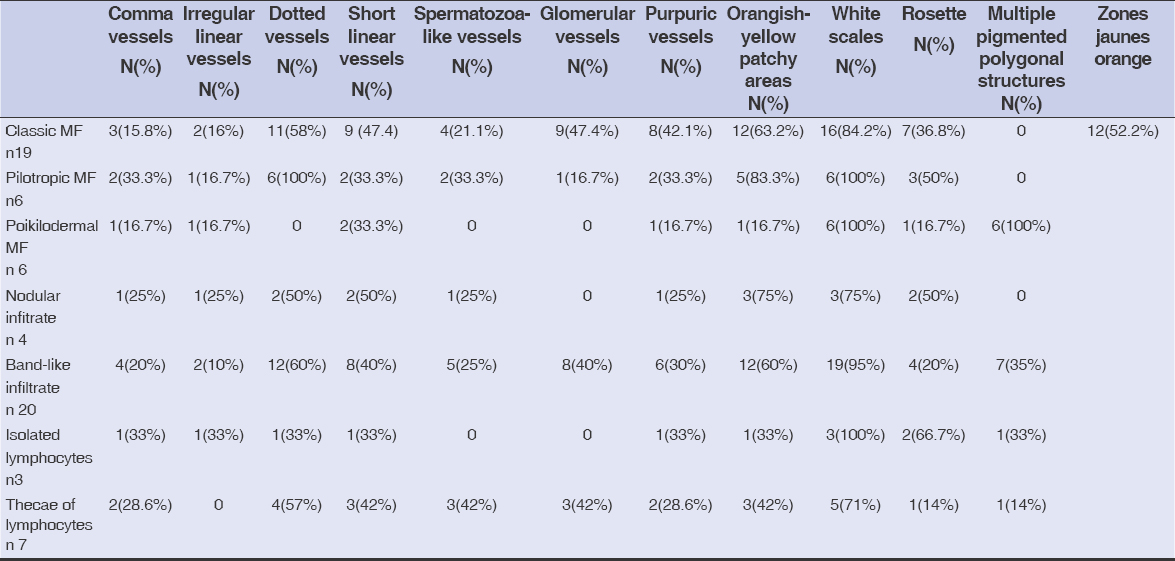

Dermoscopic findings according to the histology are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2: Dermoscopic findings according to the histology |

DISCUSSION

The prognosis of MF is generally favorable at an early stage because of the availability of skin-directed therapies, such as topical glucocorticosteroids, nitrogen mustard lotion, and phototherapy. By contrast, for patients with an advanced disease, the prognosis is unfavorable, owing to the unavailability of effective treatment [8,9]. Therefore, early diagnosis is the safest strategy to reduce disease-related mortality. However, early diagnosis of MF may be extremely difficult, owing to its non-specific clinical manifestations [10].

The dermoscopic patterns of MF were described in a series of 32 cases with early-stage MF by Lallas et al., who suggested that fine, short, linear vessels (sensitivity: 93.7%; specificity: 97.1%), together with orangish-yellow patchy areas (sensitivity: 90.6%; specificity 99.7%), represents specific criteria for the diagnosis of early MF [11]. The characteristic spermatozoa-like structures—composed of a dotted and a short, curved, linear vessel—were less common but also highly specific for the diagnosis of early MF. Bosseila et al., in a series of 25 patients with MF, confirmed the dotted pattern as the most frequently encountered vascular pattern in MF lesions, followed by the linear pattern [12]. We reached the same conclusion in our study, in which the most common vascular patterns—dotted vessels (54%), short, linear vessels (42%), and orangish-yellow areas —were found in 58% of all cases. As for the spermatozoa-like structures, they were found only in 19.4% of the cases.

Concerning poikilodermal MF, Xu et al. have described dermoscopy of this unusual variant, revealing as key dermoscopic features multiple polygonal structures consisting of lobules of white storiform streaks characterized by dotted and hairpin vessels, with septa of pigmented dots. In addition, red and yellowish smudges are detectable in poikilodermal MF [13–15]. These brown, mottled, reticular pigmentation with fine, gray dots may reflect basal pigmentation, liquefaction, and melanophages in the superficial dermis. Our study revealed the presence of these multiple polygonal pigmented structures in all patients presenting with poikilodermal MF, along with white scales and short, linear (28.6%) vessels. We also found rosettes (25%) as a new dermoscopic sign of poikilodermal mycosis fungoides, which has not been reported before in any study.

The most characteristic dermoscopic findings of keratoderma due to mycosis fungoides are relatively large amber scales on a white-to-pinkish background, sparse, whitish scales, and several non-specific reddish fissures [16]. There was only one case of keratoderma in our study, in which dermoscopy revealed dotted vessels with scales on a pink background (Fig. 4).

Regarding the correlation between dermoscopy and histology, in band-like infiltrate, we found mainly white scales, orangish-yellow patchy areas, and dotted vessels. In nodular infiltrate, we found white scales and orangish-yellow patchy areas. In isolated lymphocyte rosettes with white scales and in thecae of lymphocytes, we found whites scales and dotted vessels. Classical MF was characterized by glomerular and dotted vessels with orangish-yellow patchy areas; poikilodermal MF by multiple pigmented polygonal structures with rosettes; and pilotropic MF by dotted vessels, rosettes, and white scales.

We found no significant relationship between dermoscopy and histology (topography and morphology of the lymphoid infiltrate), which might be explained by the small size of our sample. To our knowledge, this has not been described before in the literature and others studies with larger samples are necessary to determine the validity of our results.

CONCLUSION

Our results are overall in line with previous evidence. Dermoscopy of the classical form of MF involves short linear vessels, dotted vessels, and orangish-yellow patchy areas. In poikiloderma MF, we found mainly multiple pigmented polygonal structures, as reported in the literature.

More studies should be conducted to determine the correlation of these dermoscopic structures with histological changes (morphology and topography of the lymphoid infiltrate).

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Piccolo V, Russo T, Agozzino M, Vitiello P, Caccavale S, Alfano R, Argenziano G. Dermoscopy of cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders:Where are we now?Dermatology. 2018;234:131-6.

2. Kusutani N, Sowa-Osako J, Fukai K, Maekawa N, Arai S, Kuwae Y, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis associated with Hodgkin lymphoma. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11:90-1.

3. Uzuncakmak TK, Akdeniz N, Karadag AS, Taskin S, Zemheri EI, Argenziano G. Primary cutaneous CD 30 (+) ALK (-) anaplastic large cell lymphoma with dermoscopic findings:A case report. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:59-61.

4. Mascolo M, Piccolo V, Argenziano G, Costa C, Lo Presti M, De Rosa G, et al. Dermoscopy pattern, histopathology and immunophenotype of primary cutaneous b-cell lymphoma presenting as a solitary skin nodule. Dermatology. 2016;232:203-7.

5. Caccavale S, Vitiello P, Mascolo M, Ciancia G, Argenziano G. Dermoscopy of different stages of lymphomatoid papulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e198-e200.

6. Lallas A, Giacomel J, Argenziano G, García-García B, González-Fernández D, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy in general dermatology:Practical tips for the clinician. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:514-26.

7. Errichetti E, Stinco G. The practical usefulness of dermoscopy in general dermatology. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150:533-46.

8. Trautinger F, Eder J, Assaf C, Bagot M, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome – Update 2017. Eur J Cancer. 2017;77:57-74.

9. Berg S, Villasenor-Park J, Haun P, Kim EJ. Multidisciplinary Management of Mycosis Fungoides/Sézary Syndrome. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2017;12:234-43.

10. Xu C, Liu J, Wang T, Luo Y, Liu Y. Dermoscopic patterns of early-stage mycosis fungoides in a Chinese population. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:169-75.

11. Lallas A, Apalla Z, Lefaki I, Tzellos T, Karatolias A, Sotiriou E, et al. Dermoscopy of early stage mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:617-21.

12. Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy in general dermatology:A practical overview. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:471-507.

13. Bosseila. M, Sayed Sayed. K, Salah El-Din Sayed. S, Ali Abd El Monaem. N. Evaluation of angiogenesis in early mycosis fungoides patients:dermoscopic and immunohistochemical study. Dermatology 2015;231:82–86.

14. Xu P, Tan C. Dermoscopy of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides (MF). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;4:e45–7.

15. Nojima K, Namiki T, Miura K, Tanaka M, Yokozeki H. A case of CD8+ and CD56+ cytotoxic variant of poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides:Dermoscopic features of reticular pigmentation and vascular structures. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:e236-8.

16. Errichetti E, Stinco G. Dermoscopy as a supportive instrument in the differentiation of the main types of acquired keratoderma due to dermatological disorders. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:e229-31.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 |

Comments are closed.