Atypical and fulminant non-erythrodermic Sézary syndrome

Aida Oulehri , Sara Elloudi, Hanane Baybay, Zakia Douhi, Fatima Zahra Mernissi

, Sara Elloudi, Hanane Baybay, Zakia Douhi, Fatima Zahra Mernissi

Dermatology Department of the University Hospital Center Hassan II, Fez, Morocco

Corresponding author: Aida Oulehri, MD

How to cite this article: Oulehri A, Elloudi S, Baybay H, Douhi Z, Mernissi FZ. Atypical and fulminant non-erythrodermic Sézary syndrome. Our Dermatol Online. 2021;12(3):310-313.

Submission: 26.08.2020; Acceptance: 31.10.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20213.20

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2021. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Sézary syndrome (SS) is a rare and aggressive type of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) characterized by cutaneous and systemic dissemination of clonal CD4+T cells into the blood and lymph nodes. The majority of patients with SS present the classic symptoms of erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and pruritus. However, there have been, in recent years, numerous reports of patients with SS and with non-classic signs. We report the case of a 67-year-old patient presenting non-erythrodermic Sézary syndrome with a particular clinical aspect made of diffuse and aggressive angiomatous lesions with a dermoscopic description.

Key words: Sézary syndrome; Non-erythrodermic; Angiomatous lesions; Dermoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Sézary syndrome (SS) is the leukemic subtype of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) characterized by the triad of erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and the presence of Sézary cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood [1].

In 2007, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) proposed the newest diagnostic guidelines for CTCL on the basis of developments in the understanding of T-lymphocyte tumor biology, along with molecular diagnostics and immunophenotyping advances [2]. The hematologic criteria recommended for Sézary syndrome are intended to identify patients with a worse prognosis as compared with other CTCL subsets and consist of one or more of the following: an absolute Sézary cell count of 1000 cells/mm3 or higher; a CD4/CD8 ratio of 10 or higher caused by an increase in circulating T cells and/or an aberrant loss or expression of pan-T cell markers by flow cytometry; increased lymphocyte counts with evidence of a T-cell clone in the blood by the Southern blot or polymerase chain reaction technique; or a chromosomally abnormal T-cell clone [3]. In recent years, several cases have been reported in the literature of Sezary Syndrome (SS) fulfilling all the biological criteria but without erythroderma. The following non-classic symptoms of SS were identified as keratoderma, onychodystrophy, alopecia, leonine facies, ocular pathologies, peripheral neuropathy, burning or stinging pain, arthritis, papuloerythroderma of Ofuji, and lower-extremity edema [1]. We report the case of a 67-year-old patient suffering from SS with clinically absent erythroderma and atypical angiomatous lesions with a dermoscopic description. This is the first case in the literature of SS with such a clinical presentation. We also report the overwhelming evolution of the tumoral lesions in a short period of time, always confirming the very aggressive nature of this entity.

CASE REPORT

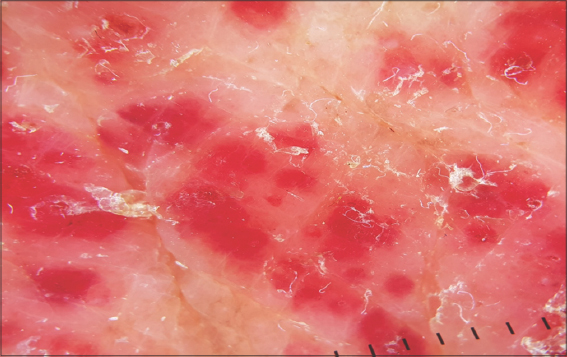

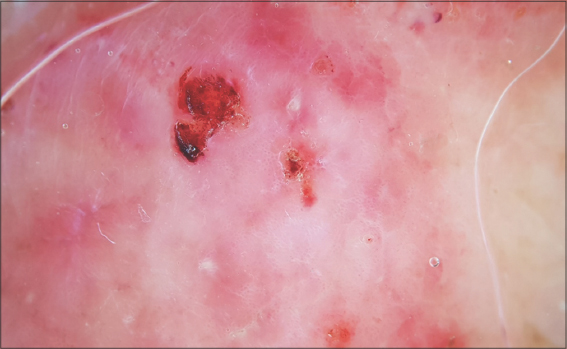

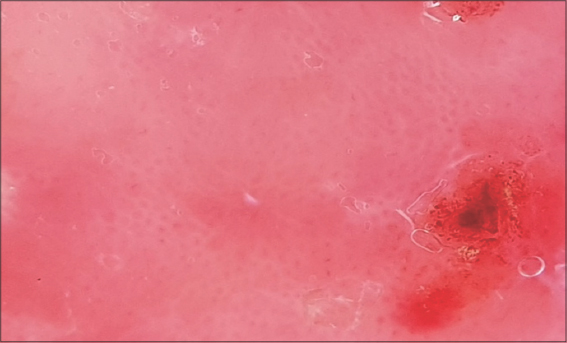

A 67-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with a one-year history of general itching, then the appearance of acutely pruriginous erythematous papules on the face and neck persistent for six months, which were formerly treated with topical steroids without improvement. A physical examination (Figs. 1−3) revealed multiple diffuse erythematous and angiomatous papules, nodules, and tumors on the face, scalp, trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and upper and lower limbs, most of which had eroded surfaces and were surmounted by hemorrhagic crusts. The largest lesion was a rounded tumor with a six-centimeter long axis and with an eroded and bleeding surface at the nape of the neck. The face had a leonine appearance with several confluent angiomatous tumors. The affected skin surface was estimated at 70%. Dermoscopy revealed red lagoons separated by fibrous septa, confirming the angiomatous nature of these lesions (Fig. 4). We found pink-to-white structureless areas (Fig. 5) and, at very high magnifications, fine short linear vessels, dotted vessels, and spermatozoa-like structures in some tumor lesions (Fig. 6).

The patient also had bilateral angular cheilitis, multiple pinhead angiomatous papules in the scrotum and penis, fissuring plantar keratoderma, and diffuse nail onychodystrophy. An examination of lymph node areas revealed bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. The rest of the somatic examination showed homogeneous splenomegaly reaching as far as the umbilicus.

A skin biopsy specimen taken from the tumor lesion revealed infiltration of atypical lymphocytes in the upper dermis without epidermotropism. Blood count showed hyperlymphocytosis at 68,000 with normal differential cell counts of neutrophils and monocytes, but persistent eosinophilia and moderate thrombocytopenia were observed. A search for Sézary cells in the peripheral blood associated with lymphocyte immunophenotyping indicated the presence of an atypical T lymphoid population—CD4+, CD8−, CD3+, CD5+, CD2+, CD7−, CD57−, CD56−, CD16−—expressing alpha-beta TCR; these cells represented about 95% of lymphocytes. Cytologically, they were medium-to-large cells with a cerebriform nucleus (95% of Sézary cells). The CD4/CD8 ratio was 52.1. Beta-2 microglobulin was above 4 mg/L, and LDH was three times normal. In the absence of the availability of PCR, we retained Sézary syndrome on this cluster of clinical and biological arguments. The patient then underwent an extension workup consisting of an ultrasound scan of lymph node areas, which showed bilateral inguinal and axillary adenopathy suspected of malignancy. However, a cervico-thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan and osteo-medullary biopsy were without particularity. The decision was to put the patient under CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin (vincristine), prednisone) chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the patient died after a single course of treatment.

DISCUSSION

In 2000, Tokura et al. were the first authors to report a patient with SS without erythroderma. The clinical presentation was quite similar to our case, with multiple papules, nodules, and tumors, but it was an indolent form, which is the exact opposite of our case [4]. Lately, Thompson et al. identified a distinct and atypical population of SS patients with a high blood tumor burden of Sézary cells, fulfilling the criteria for SS but without fulfilling the criteria for erythroderma. Among the 16 patients identified, all had cutaneous findings consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, most commonly erythematous patches and plaques. Survival was not different between patients with SS with and without erythroderma. The authors confirmed that erythroderma may not be a necessary element in the diagnosis of SS and proposed that these atypical cases would be more precisely described with the TNMB classification [2]. Moreover, a retrospective, multicenter chart review was performed for 263 confirmed cases of SS diagnosed from 1976 through 2015; erythroderma was the earliest recorded skin sign of SS in only 25.5% of cases. In patients without erythroderma, during their initial visit, the first cutaneous signs of SS were nonspecific dermatitis (49%), atopic dermatitis-like eruption (4.9%), or patches and plaques of mycosis fungoides (10.6%). The mean diagnostic delay was 2.2 years for cases involving erythroderma on the initial presentation and 5 years for cases not involving erythroderma on the initial presentation. The authors conclude that early SS should be considered in cases of non-erythrodermic dermatitis that is refractory to conventional treatments [5].

This conclusion is very important for the daily practice of physicians. We would like to add to this that our patient presented chronic pruritus without any lesions for one year, then presented a nonspecific pruritic dermatitis for another six months, treated only symptomatically, which, unfortunately, considerably delayed the diagnosis and management of SS.

Several authors reported that all their patients with SS had eventually developed erythroderma, whatever their initial clinical presentation [6–7]. On the other hand, Henn et al. [8] reported that the six cases in their series never developed erythroderma throughout the course of the disease. Mangold et al. [5] also showed that 13 out of 23 cases did not develop erythroderma during the course of the disease. Thus, not all SS patients without initial erythroderma eventually progress to erythroderma. This is also the case in our patient, who developed several nodules and tumors during a follow-up but never erythroderma.

To characterize the clinical skin findings, Hiroaki et al. summarized 37 cases of SS without initial erythroderma; the skin manifestations varied from patches and plaques to tumors, often found in patients with mycosis fungoides, as well as and other rarer findings, such as excoriations, palmoplantar keratoderma, and alopecia. Pruritus was reported in most patients. Interestingly, five cases of SS without erythroderma had no apparent cutaneous findings, while specimens taken from their skin tissue revealed dermal perivascular atypical lymphocyte infiltration, consistent with SS [1,9].

Our patient also had chronic pruritus without skin lesions for one year and then developed multiple diffuse and aggressive angiomatous tumors. Concerning dermoscopy, to our knowledge and based on a recent review of the literature, this is the first description of dermoscopy for non-erythrodermic SS reported in the literature [10].

SS is an aggressive epidermotropic CTCL with a five-year survival rate of 24% [11]. It is, therefore, interesting to know whether the survival of patients with non-erythrodermic SS would be different from patients with erythroderma. The results found so far in the literature remain contradictory. Henn et al. [8] showed a better survival rate for non-erythrodermic SS. Conversely, Thompson et al. [2] suggested that non-erythrodermic SS had a similar prognosis. In our patient, the evolution was dramatic with a spectacular extension of the tumors to the whole skin and death after one month from the diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Sézary syndrome is a very aggressive cutaneous lymphoma, and the diversity of clinical aspects described in recent years leads us to consider it one of the great simulators of dermatology.

Awareness and information among dermatological practitioners and, especially, general practitioners are immensely important in the context of this syndrome, which may become fatal with delayed diagnosis, as our case illustrates.

We also suggest that erythroderma should no longer be linked to Sézary syndrome and that a new classification for this syndrome is necessary.

Finally, we report the clinical and dermoscopic aspect of these angiomatous tumors as a new atypical description of this syndrome.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms, in which the patients gave their consent for images and other clinical information to be included in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due effort will be made to conceal their identity, but that anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Morris L, Tran J, Duvic M. Non-classic signs of Sézary syndrome:A review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:383-91.

2. Thompson AK, Killian JM, Weaver AL, Pittelkow MR, Davis MD. Sézary syndrome without erythroderma:A review of 16 cases at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:683-8.

3. Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, Burg G, Duvic M, Heald P, Laroche L, et al. Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma:report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:95-106.

4. Tokura Y, Yagi H, Seo N, Takagi T, Takigawa M. Nonerythrodermic, leukemic variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with indolent clinical course:Th2-type tumor cells lacking T-cell receptor/CD3 expression and coinfiltrating tumoricidal CD8 T cells. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:946-54.

5. Mangold AR, Thompson AK, Davis MD, Saulite I, Cozzio A, Guenova E, et al. Early clinical manifestations of Sézary syndrome:A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:719-27.

6. Marti RM, Pujol RM, Servitje O, Palou J, Romagosa V, Bordes R, et al. Sézary syndrome and related variants of classic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. A descriptive and prognostic clinicopathologic study of 29 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:59-69.

7. Foulc P, N’Guyen JM, Dréno B. Prognostic factors in Sézary syndrome:A study of 28 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1152-8.

8. Henn A, Michel L, Fite C, Deschamps L, Ortonne N, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Sézary syndrome without erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1003-9.e1.

9. Shiue LH, Ni X, Prieto VG, Jorgensen JL, Curry JL, Goswami M, et al. A case of invisible leukemic cutaneous T cell lymphoma with a regulatory T cell clone. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1111-4.

10. Bombonato C, Pampena R, Lallas A, Giovanni P, Longo C. Dermoscopy of lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:377-88.

11. Caudron A, Marie-Cardine A, Bensussan A, Bagot M. Actualités sur le syndrome de Sézary. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 2012;139:31-40.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5942-441X http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3455-3810 |

Comments are closed.