Herpes simplex virus serology in genital ulcer disease in a tertiary care hospital

Anurag Tiwary1, Romita Bachaspatimayum 2,

2,

1Department of General Surgery, Dr D.Y. Patil Medical College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai, India, 2Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, RIMS, Imphal, Manipur, India

Corresponding author: Dr. Romita Bachaspatimayum

Submission: 05.08.2020; Acceptance: 06.09.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.2020S3.2

Cite this article: Tiwary A, Bachaspatimayum R. Herpes simplex virus serology in genital ulcer disease in a tertiary care hospital. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(Supp. 3):6-9.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

Background: Herpes genitalis is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI). A herpes simplex virus (HSV) serology test may help in confirming the diagnosis and in identifying asymptomatic cases. Recently, there has been a rise in cases of genital lesions due to HSV-1.

Materials and Methods: This study was conducted for a period of one and a half years on patients presenting themselves with genital ulcers in the STI clinic. HSV-1 and HSV- 2 serology tests were conducted on all the patients and data was analyzed with descriptive statistics.

Results: Out of a total number of 68 patients, IgG and IgM were positive in 76.48% and 29.41% of the patients, respectively, for HSV-1. In HSV-2 serology, IgG and IgM were positive in 60.30% and 27.94% of the patients, respectively. Seroprevalence was higher in females.

Conclusion: HSV-1 serology positivity was found to be higher than HSV-2, which may indicate the rising incidence of HSV-1 causing genital herpes.

Key words: Herpes genitalis; Genital ulcer disease; HSV serology

INTRODUCTION

Herpes genitalis is caused by the herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) consisting of two distinct serovars: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-2 is usually associated with genital infections and is usually diagnosed clinically, but a laboratory confirmation is required particularly because of other conditions with similar presentations. Type-specific HSV antibodies are based on type-specific proteins—gG1 and gG2—and can distinguish between HSV-1 and HSV-2 infections. In practice, the diagnosis is usually reached on clinical grounds and with Tzanck smear, while culture, serology, immunofluorescence, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are available only in research centers [1]. Lately, there has been an increasing incidence of HSV-1 causing genital lesions [2,3].

AIMS AND OBJECTS

This study was undertaken to investigate the prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 serology in patients with STIrelated genital ulcers attending the STI clinic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted for a period of one and a half years on patients presenting themselves with genital ulcers in the STI clinic at a tertiary care center in northeast India. HSV-1 and HSV-2 serology (IgG and IgM) tests were undertaken on all patients after taking written consent. HSV serology tests were based on the classic ELISA technique. Descriptive statistics was used to analyze the data. All patients with STI-related genital ulcers willing to undergo the tests were included in the study group, while those with non-venereal genital ulcers, those unwilling to undergo the tests, and those lost to follow-up were excluded from the study.

RESULTS

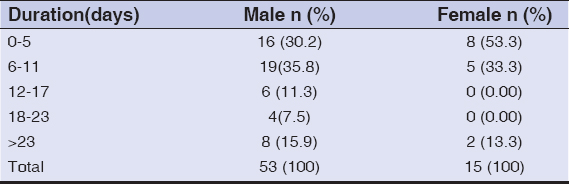

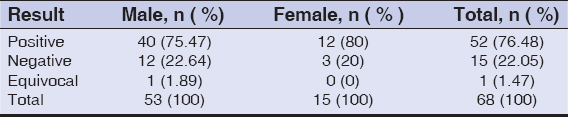

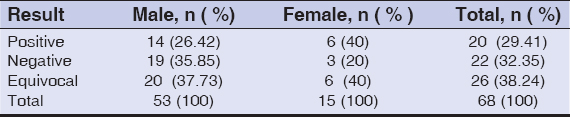

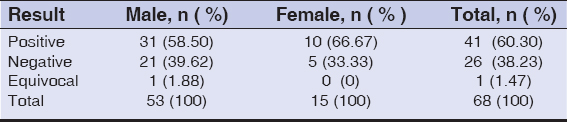

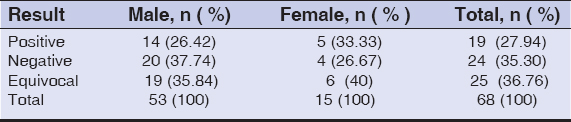

Out of a total of 68 patients, 53 were males and 15 were females. Sixty-four patients were clinically diagnosed with herpes genitalis, three were cases of syphilis, and one was a case of chancroid. The mean duration of disease in males at the time of presentation was 13.52 days while, in females, it was 10.06 days. Table 1 presents the distribution of the duration of disease in the study. Most (30.2%) of the male patients presented themselves after 6–11 days while the majority (53.3%) of females reported earlier, around 0–5 days after the onset of disease. Tables 2a and 2b show HSV-1 serology reports. IgG and IgM were positive in 76.47% and 29.41% of patients, respectively. The seropositivity was higher among females than among males for both IgG and IgM. The results were negative in 22.05% and 32.35% for IgG and IgM, respectively. Tables 3a and 3b show HSV-2 serology findings. IgG and IgM were positive in 60.30% and 27.94%, respectively, with a higher seropositivity rate in females than in males. However, the serology test was negative in 38.23% and 35.30% for IgG and IgM, respectively. IgG of both HSV1 and HSV-2 was positive in 27 (39.7%) patients; IgM of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 was positive in six (8.8%) patients; while IgG and IgM of both HSV-1 and HSV2 were positive in 11 (16.2%) patients. There were four (5.8%) patients in whom only IgG for HSV-1 was positive, a single patient in whom IgM for HSV-2 was positive, and no patients in whom only IgG for HSV-2 was positive. In seven (10.3%) patients, the serology was negative for IgG and IgM for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. Among non-herpetic cases, one case of chancroid had positive serology for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 and one case of syphilis had positive serology for HSV-1 (IgG) only. There was a single patient with herpes genitalis presenting themself with herpes labialis and whose IgG for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 were positive while IgM was equivocal for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. None of the other patients had oral lesions suggestive of herpes simplex labialis. The maximum positivity for both HSV-1 and HSV-2 serology was found in the age group of 21–30 years with 19 (27.94%) and 17 (25%) cases, respectively, followed by the age group of 31–40 years with 13 (19.12%) and eight (11.76%) cases, respectively, the most common age group for GUD in the study period. IgG was positive in patients who reported their symptoms as the first episode and IgM was positive in patients with a history of recurrence. Five (7.3%) patients were found to be HIV-infected, out of which three were males.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of STI during the study period was 2.52% (males: 67.20%; females: 32.79%), out of which GUD constituted 11.01%. The prevalence of STI remained more or less steady compared to an earlier study in the same setting [4].

Serologies for HSV-1 and HSV-2 were done for 68 patients. IgG and IgM were positive in 76.47% and 29.41%, respectively, for HSV-1, while IgG and IgM were positive in 60.29% and 27.94%, respectively, for HSV-2. The age group of 31–40 years was the most common age group for GUD during the study period, as well as for STI in a previous study. [4] In a study on STI among high-risk individuals, the incidence of any STI was the greatest among those aged 25–34 years [5]. However, HSV seropositivity was most common in the younger age group (21–30 years) in this study. HSV-2 positivity rose markedly with age in females while, in males, it remained low in the younger age group [6]. Another study also reported lower seropositivity in the younger age groups [3]. Seropositivity was comparatively higher in females than in males for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. For HSV-1, IgG seroprevalence was 80% and 75.47% and IgM seroprevalence was 40% and 26.42%, respectively, in females and males. For HSV-2, IgG seroprevalence was 66.67% and 58.5% with an IgM seroprevalence of 33.3% and 26.42%, respectively, in females and males. A study from Karnataka also showed a higher prevalence of HSV-2 serology in females [7].

In the study, IgG was still positive even if patients reported their symptoms as the first episode and IgM was positive even though patients gave a history of recurrence. This may be due to the fact that some patients may already have been infected subclinically or that they may have failed to recognize the clinical signs due to the varied modes of presentation of herpes genitalis. Serological tests were advised regardless of the duration of disease at the time of presentation due to the possibility of patients not turning up for subsequent follow-ups due to the stigma associated with STI. The median time to seroconversion is generally 2–3 weeks after infection, and seroconversion may be delayed up to six months after infection [8]. Moreover, the absence of antibodies to gG-1 and gG-2 does not necessarily rule out the presence of an HSV infection. A negative HSV serology only implies that one has made no antibodies to a particular antigen and a false negative result may occur if the humoral immune response to gG is inadequate or delayed, or if the infecting virus is gG-deficient [9]. In the aforementioned study, IgG of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 was positive in 27 (39.7%) patients; IgM of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 was positive in six (8.8%) patients; while IgG and IgM of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 were positive in eleven (16.2%) patients. Whether these findings denote co-infection with both HSV-1 and HSV-2 needs further evaluation, as only one patient had both oral and genital lesions, and the rest of the patients denied a history of oral lesions. HSV-1 has been identified as the causative agent in the majority of first-episode genital herpes infections [3,8].

In a study from Mumbai, among patients with clinical evidence of genital herpes, 94.2% were positive for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. In the cases of first-episode herpes genitalis, 66% were positive for HSV-1 and HSV-2, whereas, in recurrent genital herpes, 96.4% were positive for HSV-1 and HSV-2. 72.6% of patients without a history suggestive of genital herpes were positive for HSV-2 serology [2]. In the above study, 7.3% of the patients were found to be HIV-infected. In HIV-infected patients, genital herpes may result in severe and atypical clinical presentations [11], which was also seen in some of our patients. There has been evidence of a direct effect of HSV-2 infection on HIV acquisition along with a significantly higher HIV risk associated with the incidence of HSV-2 infection than with prevalent HSV-2 infection [10,11].

CONCLUSION

In the above study, HSV-1 serology was found to be more prevalent than HSV-2 in patients with genital ulcers. Besides, seroprevalence was higher among females than among males for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. More randomized controlled studies with larger sample sizes are recommended in view of the importance of the transmission and acquisition of HIV in association with viral STI-like genital herpes.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 2008 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients.

REFERENCES

1. Sharma VK, Kumar U. Clinical Approach to Genital Ulcer Disease. In:Sharma VK, editor. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS. 2nd Ed. New Delhi:VIVA Books;2009.p.768-73.

2. Tamer F, Yuksel ME, Avce E. Should patients with anogenital warts be tested for genital herpes?Initial results of a pilot study. Our Dermatol Online. 2019;10:329-32.

3. Khadr L, Harfouche M, Omori R, Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. The epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 1 in asia:systematic review, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68:757–7.

4. Devi NS, Singh LS, Bachaspatimayum R, Zamzachin G, Devi ThB, Singh ThN. Pattern of STI cases attending RIMS hospital. JMS. 2010;20:71-3.

5. Ryan KE, Asselin J, Fairley CK, Armishaw J, Lal L, Nguyen L, et al. Trends in human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infection testing among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men after rapid scale-up of preexposure prophylaxis in Victoria, Australia. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47:516-24.

6. Shaw M, Sande MvdM, West B, Paine K, Ceesay S, Bailey R, et al. Prevalence of herpes simplex type 2 and syphilis serology among young adults in a rural Gambian community. Sex Transm Inf. 2001;77:358-65.

7. Becker M, Stephen J, Moses S, Washington R, Maclean I, Cheang M, et al. Etiology and determinants of sexually transmitted infections in Karnataka state, south India. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:159-64.

8. Ward BJ, Plourde P. Travel and sexually transmitted infections. J Travel Med. 2006;13:300-17.

9. Nguyen N, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Identifying potential pitfalls in conventional herpes simplex virus management. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:987-93.

10. Looker KJ, Elmes JAR, Gottleib SL, Schiffer JT, Vickerman P, Turner KME, et al. Effect of HSV-2 infection on subsequent HIV acquisition:an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1303-16.

11. Looker KJ, Welton NJ, Sabin KM, Dalal S, Vickerman P, Turner KME, et al. Global and regional estimates of the contribution of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection to HIV incidence:a population attributable fraction analysis using published epidemiological data. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:240-9.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

|

Comments are closed.