|

|

Unmasking the mask: COVID-19 manifestations of PPE kits

Santhanakrishnaan Soundarya, Srinivasan Sundaramoorthy

Department of Dermatology, Chettinad Hospital and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Tamil Nadu, India

Corresponding author: Prof. Srinivasan Sundaramoorthy, MD PhD

Submission: 17.09.2020; Acceptance: 10.11.2020

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.2020e.186

Cite this article: Soundarya s, Sundaramoorthy S. Unmasking the mask: COVID-19 manifestations of PPE kits. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(4):e186.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

ABSTRACT

The world is now facing a new unexpected pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2, which is a coronavirus that mainly targets the lungs, a very vital and sensitive organ of the body. Research and healthcare workers are still struggling to contain the disease and eradicate the virus. Before the invention of a vaccine, the virus may take at least several more millions of lives. On top of this, dermatologists are facing numerous challenges because of the regulations put forward by the WHO and local governments. This article discusses in detail various dermatological eruptions caused by the personal protective equipment (PPE) used in combating the disease. This should be an eye-opener for dermatologists worldwide.

Key words: COVID-19; Pandemic; PPE kits; Masks

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the virus named SARS-CoV-2, was first reported in Wuhan, China, in 2019, and then rapidly spread to more than 200 countries across the globe [1]. Its transmission mainly occurs through droplets and aerosols spread by an affected person, whether symptomatic or asymptomatic, but the former being more contagious than the latter [2,3]. The droplets may land on the objects and surfaces that others will touch and become infected by, then, touching their face around the nose, mouth, and eyes.

To avoid the spread of infection, people are advised to exercise simple measures such as social distancing of at least 1 m, washing hands frequently with soap and water for a minimum of twenty seconds, using sanitizers with at least 60% alcohol content, and using masks.

However, these protective measures themselves predispose to the development of various dermatoses in a previously normal patient or predisposed individual, especially in healthcare workers.

The skin performs various dynamic and complex functions, such as barrier function (both physical and chemical), immunological regulation, thermoregulation, sensory function, synthesis of vitamin D, wound repair, and regeneration and is, above all, regarded as an organ of beauty.

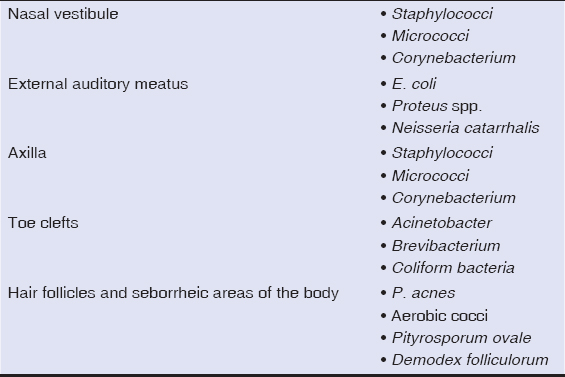

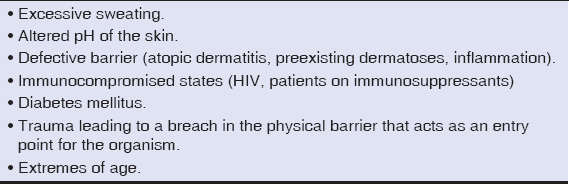

This largest organ of the body harbors an ecosystem of microorganisms (commensals) (Table 1). These organisms live in harmony with the host without causing disease. However, under certain circumstances, these organisms exceed normal amounts and colonize to produce infections (Table 2).

|

Table 1: Commensals of the skin specific to different sites [4,5]. |

|

Table 2: Favorable circumstances for infection by commensals. |

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

The WHO recommends that only people directly in contact with COVID-19-positive patients should wear N95 or FFP 2 masks [6]. A PPE kit comprising a medical mask, gown, gloves, and eye protection in the form of goggles or a face shield is sufficient [6].

People not handling positive cases and the ordinary public population are not required to wear N95 masks, as per the CDC guidelines.

Techniques of Wearing a Mask

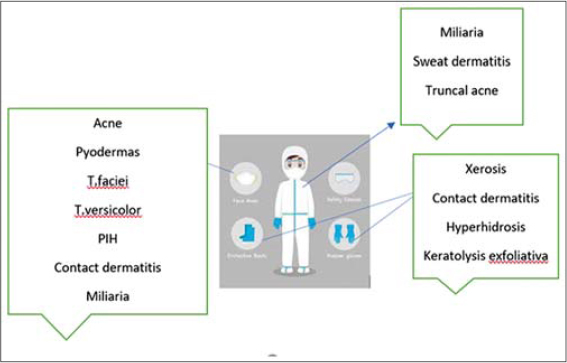

The mask should fit correctly, that is, while breathing, the air should not pass into the eyes, and should cover the nose, mouth, and chin properly (Fig. 1), as these areas are more prone to the deleterious effects, and the consequent dermatoses, of wearing a mask (Fig. 2) (Table 3).

|

Figure 1: The proper technique to wear a mask covering the nose, mouth and chin. |

|

Figure 2: The common sites and common dermatoses caused by PPE kits. |

|

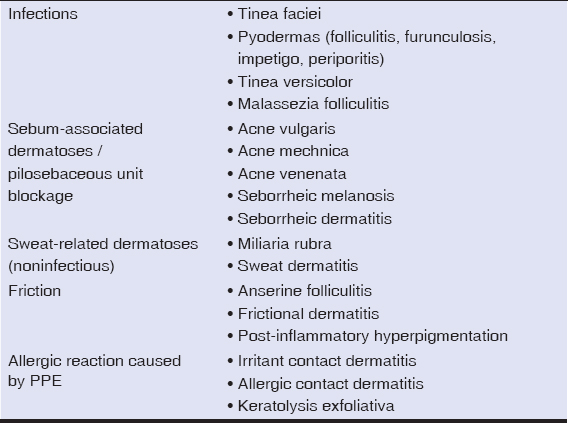

Table 3: Dermatoses caused by PPE kits. |

Mechanisms of Predisposition to Various Dermatoses

Nowadays, wearing a mask has become a routine of day-to-day life, as it is not practical or possible to maintain social distance at each and every point of everyday social life, especially at the workplace and in public places.

A mask covers the nose, cheeks, mouth, and chin. During expiration, the warm air is released and exposes the area under the mask to excessive heat and humidity. The primary mechanism of heat dissipation by the body is eccrine sweating. Hence, this area naturally sweats more, which makes the patient more prone to develop sweat-related disorders, such as miliaria, sweat dermatitis, and infections such as dermatophytosis, pityriasis versicolor, and pyodermas.

Because people tend to avoid visiting the hospital due to fear of contracting a COVID-19 infection, they purchase OTC drugs that contain combinations of mostly antifungal, antibiotic, and steroid ingredients as predominant components, which produce their own side effects, also aiding in the spread of infection.

Most of the patients are of low socioeconomic status and cannot afford to purchase disposable masks on a daily basis. Because of this, they continue to use the same mask for days without the awareness of the consequences, as such a mask will contain sweat, dirt, sebum, and infective particles, promoting the spread and continuation of the infection. A higher temperature also causes seborrhea and acne.

Because N95 masks are costly and may be reused, many people use them for days, especially when venturing out. The area under the mask provides a favorable sweaty, macerated, and occlusive environment for the fungus that makes the patient susceptible to infection. Breaks in the skin, a defective skin barrier, and maceration aid in the penetration and persistence of the infection.

Various masks are available on the market for use, including surgical masks, FFP1, FFP2, and FFP3 respirators, N95 masks with or without a valve, N100 masks, homemade cotton masks, two-layer pleated cotton masks, polypropylene masks, bandanas, sponge masks, pitta masks, and masks with activated carbon.

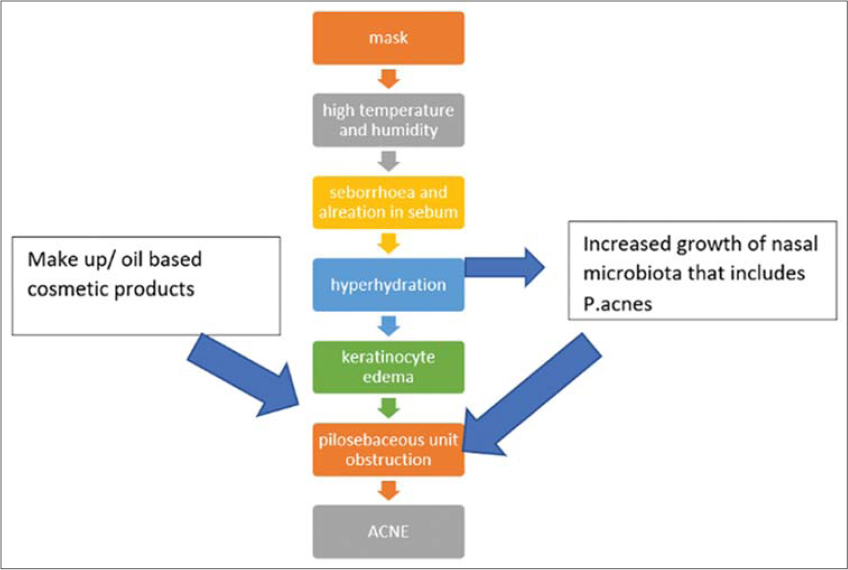

People in India also wear handkerchiefs and duppattas as masks without properly washing them. Mechanisms of predisposition to various dermatoses are presented in Fig. 3.

|

Figure 3: Mechanisms of predisposition to various dermatoses. |

INFECTIONS

Tinea Faciei

Tinea faciei is a common superficial mycosis caused by dermatophytes that involves the stratum corneum of the face. Its prevalence is higher in hot and humid climates. Hyperhidrosis and maceration aid in the penetration and persistence of the infection.

Studies have demonstrated that contaminated textiles, if not washed properly, retain dermatophytes, especially Trichophyton rubrum, which may, in contact with sterile clothes, be transferred, thus promoting infection of family members via textile-bound infectious material through skin contact. Trichophyton rubrum may be recovered from clothes even after washing at 30°C. However, washing clothes at 60°C eliminates the fungus [7].

Tinea Versicolor

Tinea versicolor is a superficial mycosis caused by the Malassezia species that manifests itself with well-defined hyperpigmented or hypopigmented erythematous macules with branny scales, commonly affecting the seborrheic areas of the body. These organisms are commensals of the skin that overgrow in favorable conditions such as hot and humid climates, increased perspiration, synthetic clothing (masks), occlusion, increased CO2 concentration, and altered pH and microbiome [8,9].

PYODERMAS

Around 20–80% of the human population are asymptomatic carriers of S. aureus in the anterior nares. In a study conducted on nasal microbiomes of 178 adults, 90.4% had S. aureus, 83.7% had P. acnes, and 88.2% had Corynebacterium [10]. With epidermal barrier dysfunction and in a favorable environment such as maceration and irritation, these organisms produce pyodermas. They may secondarily infect sweat ducts to produce tiny abscesses leading to periporitis.

SEBUM-ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Sebum excretion is directly proportional to temperature. Sebum excretion increases by 10% for every 1°C rise in temperature [11]. There is alteration in skin surface lipids where squalene increases. A positive correlation was found between the degree of squalene peroxidation and the size of the comedones elicited [12]. People experience more seborrhea in the summer than in the winter. The T and U areas of the face are commonly affected [13]. Both temperature and humidity precipitate acne [14]. The mechanism of acne aggravation by the use of masks is presented in Fig. 4.

|

Figure 4: The mechanism of mask-induced acne (“maskne”). |

The acne associated with the use of masks has an irritant component, especially itching and a burning sensation that provoke the patient to touch the face repeatedly, leading to the spread of the infection. Surgical masks should be replaced every four hours, while N95 masks should be replaced every three days [11].

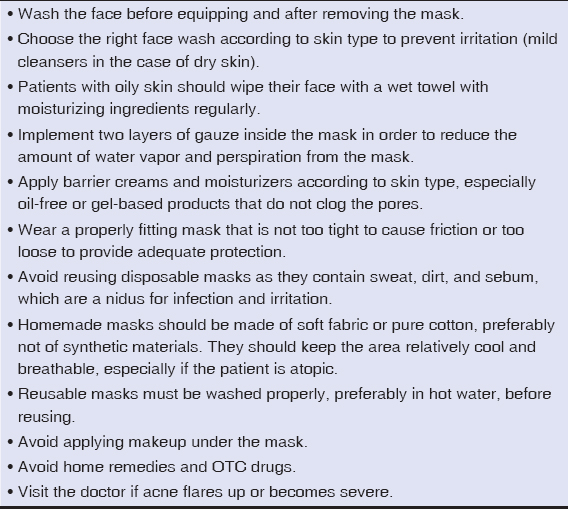

The treatment modality for acne remains the same but, in these patients, with an already irritated and inflamed skin, the risk of contact dermatitis increases, especially of retinoid dermatitis. The steps to prevent mask-induced acne are presented in Table 4.

|

Table 4: The steps to “maskne” prevention. |

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is facilitated by a hot and humid environment, which is provided by PPE kits. People with SD are prone to irritation from sodium lauryl sulfate used in soaps, shampoos, and other cosmetic products [15].

SEBORRHEIC MELANOSIS

Seborrheic melanosis is a localized darkening of seborrheic areas of the face, such as the nasolabial folds, labiomental creases, and the angles of the mouth. Most often, patients have coexisting seborrheic dermatitis, and most patients have prominent alae nasi that promote the stasis of sebum on the alar grooves. Additional factors such as frequent rubbing and cosmetics-induced irritation contribute to the pigmentation associated with seborrheic melanosis [16].

SWEAT-RELATED DISORDERS

Sweat Dermatitis

The body possesses a compensatory cooling mechanism that produces sweat in hot environments. During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers need to wear PPE kits for long periods of time, which translates to occlusive clothing and an ill-ventilated environment. The sweat cannot easily escape or evaporate from the body and stagnates instead [17]. This, as a consequence, soaks the clothing in sweat. Some of the unrinsed detergents also seeps from the clothing onto the sweaty skin, predisposing to contact dermatitis [18]. Patients wearing PPE kits wear three layers of clothing—innerwear, formal wear, and a PPE kit—which creates an ill-ventilated and occlusive environment.

This may create irritant reaction, especially in the areas of intertriginous regions and sites of friction with clothing, such as the waist, and collar, leading to frictional sweat dermatitis. As a consequence, patients present themselves with burning, itching, and stinging, as well as roughness and scaling [17].

Miliaria Rubra

Miliaria rubra is a sweat-retention syndrome caused by the blockage or obstruction of intraepidermal sweat ducts at the level of the stratum granulosum or below it. This leads to overhydration of the stratum corneum, which blocks the sweat ducts [18].

The overhydration causes a three-fold increase in resident bacteria, causing secondary infection of the obstructed duct, leading, then, to an abscess known as periporitis.

Increasing numbers of cases of miliaria rubra are being reported due to the occlusive environment created by PPE kits.

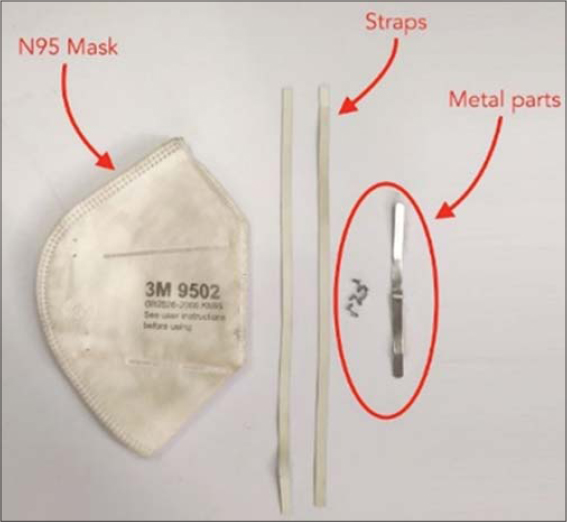

Friction-Associated Dermatoses

Friction occurs at the sites of contact with the mask, especially at the nasal bridge, the straps behind the ears, and at the margins of the mask in contact with the face. Most N95 masks come with a metal strip on the nasal clip (Fig. 5), which may lead to erythema, irritation, and irritant contact dermatitis. Constant pressure and abrasion may lead to ulceration of the nasal bridge. Constant friction leads to post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation.

|

Figure 5: The parts of the N-95 mask and the materials it is made of. |

In a study on frontline healthcare workers that involved 542 participants, around 97% of the HCWs had skin-related issues. The most commonly affected site was the nasal bridge (83.1%), a site prone to friction by the nose clip of an N95 mask (Fig. 5) [19].

Allergic Reaction Due to PPE

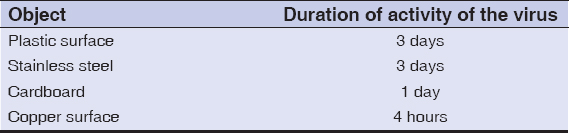

Coronaviruses may live for hours to days on surfaces of various objects (Table 5) [20], and may live in aerosols for three hours [20], hence frequent handwashing with soap and water is recommended for at least twenty seconds by the WHO. This is especially warranted in healthcare workers who take care of COVID-19 patients and collect samples.

|

Table 5: The duration of activity of corona virus on various objects. |

In a study on 376 healthcare workers, most washed their hands more than ten times per day, and only 22.1% applied proper hand creams after washing to restore the lost moisture [21].

Frequent handwashing leads to increased skin permeability by inducing edema of keratinocytes and disruption of the lipid mantle, thereby reducing the threshold for irritants, predisposing the patient to irritant contact dermatitis (ICD). Similarly, prolonged wearing of gloves leads to hyperhidrosis and higher humidity, predisposing the patient to ICD.

Soaps

Soaps contain surfactants, which denature keratin, cause alteration in the cell membrane of keratinocytes, and remove surface lipids, thereby making the skin xerotic, producing erosions and fissures, and predisposing to the development of contact dermatitis.

Patch tests with lower quantities of sodium lauryl sulfate may be used to determine individuals at a higher risk of developing contact dermatitis. However, in a pandemic during which healthcare workers play such as a vital role, this may not be feasible in all places.

HOW TO COMBAT DERMATOSES

The risk of developing dermatoses may be lowered by applying liberal amounts of moisturizer after washing the hands, using sanitizers, and removing gloves. Skin-friendly soaps with proper pH or syndet bars should be used for handwashing. People with salient features of contact dermatitis are to be given a short course of topical steroids along with moisturizers.

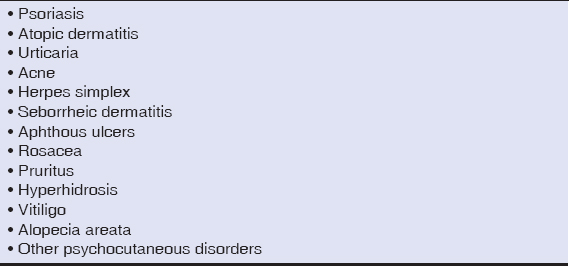

STRESS AND THE SKIN

Stress and the skin, as well as the skin conditions exacerbated by stress, are closely interrelated (Table 6) [22].

|

Table 6: Dermatoses exacerbated by stress. |

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an increased prevalence of stress and depression among the population suffering from various dermatoses [23]. Most dermatologic disorders require immunosuppressants, which should be administered judiciously during the pandemic to prevent unnecessary susceptibility to viral infection.

CONCLUSION

Because the world is now facing an emergency crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic, protection is of paramount importance so as to control the spread of the virus. Washing hands multiple times a day and the use of sanitizers and masks have become a part of the daily routine. A proper knowledge of the skin and of the adverse effects of personal protective equipment (PPE) will help patients in fighting against the pandemic without interruption.

Healthcare workers are more prone to various dermatological complications arising from existing diseases as well as to new skin eruptions. Poverty and the socioeconomic loss to the community and the government should be properly and carefully calculated and addressed so as to minimize mortality and loss of life. The world should unite without politics to conquer the pandemic and to save as many human lives as possible.

REFERENCES

1. Manchanda Y, Das S, De A. Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) facts and figures:What every dermatologist should know at this hour of need. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:251-8.

2. How COVID19 Spreads?Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC);2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. [Retrieved on 2020 Apr 03].

3. Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin DY, Chen L, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406-7.

4. Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:244-53.

5. Sanford JA, Gallo RL. Functions of the skin microbiota in health and disease. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:370-7.

6. Lockhart SL, Duggan LV, Wax RS, Saad S, Grocott HP. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for both anesthesiologists and other airway managers:Principles and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:1005-15.

7. Hammer TR, Mucha H, Hoefer D. Infection risk by dermatophytes during storage and after domestic laundry and their temperature-dependent inactivation. Mycopathologia. 2011;171:43-9.

8. Kaur T, Singh D, Malhotra SK, Kaur A. Depigmented lesions of pityriasis versicolor:A diagnostic dilemma with review of literature. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:207-9.

9. Acharya R, Gyawalee M. Uncommon presentation of Pityriasis versicolor;hyper and hypopigmentation in a same patient with variable treatment response. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:43-5.

10. Liu CM, Price LB, Hungate BA, Abraham AG, Larsen LA, Christensen K, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and the ecology of the nasal microbiome. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1400216.

11. Han C, Shi J, Chen Y, Zhang Z. Increased flare of acne caused by long-time mask wearing during COVID-19 pandemic among general population. Dermatol Ther. 2020;e13704.

12. Tamer F. Relationship between diet and seborrheic dermatitis. Our Dermatol Online. 2018;9:261-4.

13. Kisiel K, Dębowska R, Dzilińska K, Radzikowska A, Pasikowska-Piwko M, Rogiewicz K, et al. New H2O2 dermocosmetic in acne skin care. Our Dermatol Online. Our Dermatol Online. 2018;9(e):e3.

14. Narang I, Sardana K, Bajpai R, Garg VK. Seasonal aggravation of acne in summers and the effect of temperature and humidity in a study in a tropical setting. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:1098-104.

15. Araya M, Kulthanan K, Jiamton S. Clinical characteristics and quality of life of seborrheic dermatitis patients in a tropical country. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:519.

16. Verma SB, Vasani RJ, Chandrashekar L, Thomas M. Seborrheic melanosis:An entity worthy of mention in dermatological literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:285-9.

17. Soni R, Lokhande AJ, D'souza P. Atypical presentation of sweat dermatitis with review of literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:698-703.

18. Nagpal MS, Gursharan P, Aggarwal G. Miliaria- an update. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Scien. 2017;8:1161-8.

19. Elston DM. Occupational skin disease among health care workers during the coronavirus (COVID19) epidemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1085-6.

20. Suman R, Javaid M, Haleem A, Vaishya R, Bahl S, Nandan D. Sustainability of coronavirus on different surfaces. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10:386-90.

21. Lin P, Zhu S, Huang Y, Li L, Tao J, Lei T, et al. Adverse skin reactions among healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak:A survey in Wuhan and its surrounding regions. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:190-2.

22. Sellami R, Féki I, Masmoudi R, Hentati S, Turki H, Masmoudi J. Stressful lie events in alopecia areata patients:A case control study. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(e):e108.1-e108.3.

23. Rehman U, Shahnawaz MG, Khan NH, Kharshiing KD, Khursheed M, Gupta K, et al. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among Indians in Times of Covid-19 Lockdown. Community Ment Health J. 2020 Jun 23:1–7.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

|

Comments are closed.