Usefulness of dermoscopy in a pediatric case of lichen aureus

Mouna Korbi 1, Maha Lahouel1, Yosra Soua1, Hichem Belhadjali1, Monia Youssef1, Rym Hadhri2, Jameleddine Zili1

1, Maha Lahouel1, Yosra Soua1, Hichem Belhadjali1, Monia Youssef1, Rym Hadhri2, Jameleddine Zili1

1Department of Dermatology, Fattouma Bourguiba University Hospital, University of Monastir, Tunisia. 2Department of Anatomopathology, Fattouma Bourguiba University Hospital, University of Monastir, Tunisia

Corresponding author: Dr. Mouna Korbi, E-mail: korbimouna68@gmail.com

Submission: 05.10.2019; Acceptance: 10.12.2019

DOI: 10.7241/ourd.20202.36

Cite this article: Korbi M, Lahouel M, Soua Y, Belhadjali H, Youssef M, Hadhri R, Zili J. Usefulness of dermoscopy in a pediatric case of lichen aureus. Our Dermatol Online. 2020;11(2):220-221.

Citation tools:

Copyright information

© Our Dermatology Online 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by Our Dermatology Online.

Sir,

A 10-year-old girl presented with a-3-month history of asymptomatic, progressively enlarging, brownish plaque over the inner sides of both ankles. The girl was otherwise in a good health. Her medical history and systemic examination were normal. Dermatological examination revealed a well-limited brownish plaque of 3 cm of diameter located symmetrically at the ankles (Fig. 1). The clinical diagnosis in our patient was challenging evoking: nummular eczema, morphea or lichen aureus (LA).

|

Figure 1: A brownish plaque of 3 cm of diameter located on the inner side of the ankle. |

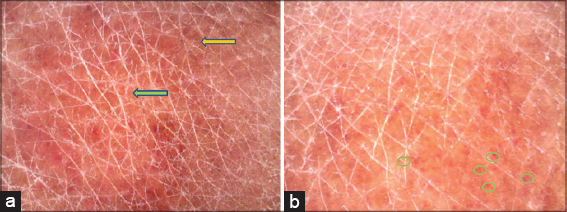

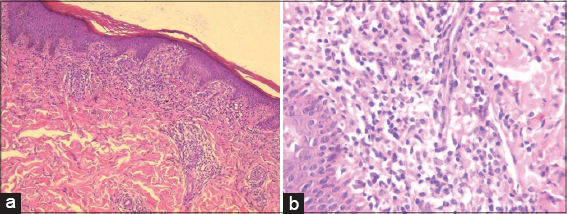

The polarizing dermoscopy examination (Dinolite®, MEDL7DW) showed coppery-red pigmentation on background, permeated by dark brown network (Fig. 2). In addition, punctuate vessels were seen especially in the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 2). The histological examination of skin biopsy revealed a band-like inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial dermis, composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes, associated with lymphocyte exocytosis, red blood cell extravasations and haemosiderin deposition leading to the diagnosis of LA (Fig. 3).

LA is a rare chronic pigmented purpuric dermatosis characterized by rust macules, papules or plaques, mainly on the legs. It occurs rarely during childhood [1]. The clinical diagnosis may be challenging leading to the practice of skin biopsy in order to rule out differential diagnosis. Zaballos et al have described, for the first time, 4 specific dermoscopic features in 3 cases of LA: (1) a grownish to coppery-red diffuse coloration of the background, (2) some gray dots, (3) round to oval red dots, globules and patches, (4) a network of brown or gray interconnected line [2]. Features (1), (3) and (4) were observed in our patient. Moreover two artilces described the same dermoscopic features in two adults with LA [3,4]. Saito et al reporte, also, the same dermosopic findings in a 3-year-old boy diagnosed with segmental LA [5]. Suh et al evaluated the dermoscopic-pathological correlation in lesions of LA. The grownish to coppery-red diffuse coloration of the background may be correlated with dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes. The gray dots correspond to hemosiderin in the dermis. The round to oval red globules are the results of an increased number of blood vessels. The network of brownish to gray interconnected lines may correlate with hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer and incontinentia pigmenti in the upper dermis [6]. Therefore, dermoscopy may help the clinician not only to confirm the diagnosis of LA but also to estimate the inflammation severity in order to better choose treatment.

Consent

The examination of the patient was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

REFERENCES

1. Kim M J, Kim, BY, Park KC, Youn SW. A case of childhood lichen aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:393-5.

2. Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus):a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290–1.

3. Fujimoto N, Nagasawa Y, Tachibana T, Inoue T, Tanaka M, Tanaka T. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1050-52.

4. Portela PS, Melo DF, Ormiga P, Oliveira FJC, Freitas NC, Bastos Jr CS. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:253-5.

5. Saito Y. Shimomoura Y, Orime M, Kariya N, Abe R. Segmental lichen aureus in infancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:215-7.

6. Suh KS, Park JB, Yang MH, Choi SY, Hwangbo H, Jang MS. Diagnostic usefulness of dermoscopy in differentiating lichen aureus from nummular eczema. J Dermatol. 2017;44:533-7.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Request permissions

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the e-mail (brzezoo77@yahoo.com) to contact with publisher.

| Related Articles | Search Authors in |

|

|

Comments are closed.