Rare case of Behcet’s disease in an African patient: A case report and review of the literature

Thomas Obiora Nnaji1, Obioma Ekpe1, Eseosa Asemota2

1Department of Internal Medicine, Federal Medical Centre Umuahia, Umuahia, Nigeria, 2Department of Dermatology, Tufts Medical Centre, 800 Washington street, Boston, USA

Corresponding author: Dr. Obioma Ekpe, E-mail: uncleprinceo@gmail.com

Submission: 07.09.2018; Acceptance: 02.11.2018

DOI:10.7241/ourd.20191.24

ABSTRACT

Behcet’s disease was first described by Hulusi Behcet, is a rare immune-mediated small-vessel vasculitis with multisystemic manifestations. Patients with this disease usually present with recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers and eye lesions. A 61 year old African man presented to the dermatology clinic with recurrent oral and penile ulcers of 26years duration, associated with grittiness of the eye and joint pains. Pathergy test was positive and ESR was elevated. Diagnosis of Behcet’s disease was made on clinical grounds. Behcet’s disease though rare could occur in patient with Fitzpatrick type VI skin and a high index of suspicion coupled with innovative approach is required to optimize patient outcome in a poor resource limited African setting.

Key words: Behcet’s disease, Fitzpatrick type-6 skin, Resource-Limited setting, Skin of color

INTRODUCTION

Behcet’s disease, first described by Hulusi Behcet, is a rare immune-mediated small-vessel vasculitis. It often presents with a triple-symptom complex of recurrent oral aphthous ulcers, genital ulcers and eye lesions [1]. This condition has seldom been reported in Africans [2]. This article reports a case of Behcet’s disease occurring in an African, and showcases the challenges of complex medical dermatology practice in resource-limited settings. It also presents a concise review of the literature on Behcet’s disease.

CASE REPORT

A 61year old African man presented to the dermatology clinic with recurrent oral and penile ulcers, of 26years duration. There was associated grittiness, redness of the eye and eye pain, as well as joint pain. There was no history of hair loss or nail abnormality, photosensitivity, proximal muscle weakness or muscle pain.

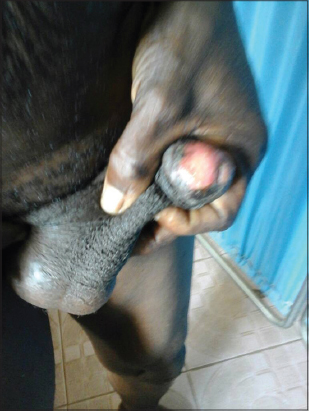

On examination, there were tender, punched-out ulcers on the tongue and penis, as well as erosions on the palate and buccal mucosa (Figs. 1 and 2). There were several areas of post inflammatory hyperpigmentation in these regions.

Appropriate investigations were requested. ESR was elevated at 62mm/hr. Full blood count was within normal limits. HIV screening, syphilis tests and hepatitis panel were negative. Pathergy test was positive. The patient declined biopsy of ulcers due to financial constraints.

Based on clinical judgment and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of Behcet’s disease was made.

Over the course of four months, he has been treated with methylprednisone cream, oral prednisone, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, arthrotec (Diclofenac/misoprostol), azathioprine. He was also referred to the ophthalmologist. Follow up visit is conducted monthly. Despite, inconsistent use of medications due to financial constraints, a progressive healing of ulcers, and reduction in ulcer occurrence, reduction in eye and joint symptoms are being observed.

DISCUSSION

Behcet’s disease is primarily a clinical diagnosis. It is a multi-system disease that manifests with orogenital ulceration [1]. Other findings may include arthritis, gastrointestinal lesions, neurological involvement, aneurysm and thrombophlebitis, erythema nodosum etc.

Behcet’s disease has a higher prevalence in Mediterranean region, Middle East and East Asia [2].

It is rare in Northern Europe, Africa and America. Disease onset is usually in the third and fourth decade of life.

The pathogenesis is hypothesized to be a combination of hereditary and environmental factors [3].

Familial cases demonstrate genetic anticipation. IL-6 and TNF-alpha has been shown to be elevated and IL-10 decreased, compared with controls. There is an association with HLA-B51.

Biopsy of the ulcers reveal neutrophilic, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates. Occasionally necrotising vasculitis is observed [4]. Pathergy test is typically positive, with elevation of inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP [3,4]. Based on the systems involved, appropriate investigations should be conducted such as endoscopy, angiography etc.

Two sets of criteria are commonly used for diagnosis of Behcet’s disease- the International criteria for Behcet’s disease, and the O’Duffy criteria [5].

Differential diagnosis includes traumatic ulceration, syphilis, Chancroid, Herpes simplex ulcers, systemic lupus erythematosus, reiter disease.

The choice of treatment depends on organs affected and disease severity [3,6]. Therapy include potent topical and systemic steroids, cytotoxic medications (e.g azathioprine, dapsone, Colchicine methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, thalidomide,), biologics (e.g etanercept, infliximab), oral antibiotics, pain relief agents, antiseptics.

Behcet’s disease has an undulating course of exacerbations and remissions, with worse prognosis in males. Complications include blindness from ocular involvement, vascular aneurysm rupture and hemorrhage, progression to dementia from Neuro-Behcet syndrome, and side effects from long-term treatment regimens.

CONCLUSION

This case report demonstrates that, although rare, Behcet’s disease could manifest in Fitzpatrick type VI skin. It also highlights the challenges of managing complex medical dermatology cases in resource-limited settings.6 Pertinent issues include unaffordability and unavailability of essential medications and diagnostic tests. An innovative approach, coupled with high clinical acumen, is required to optimize patient outcomes.

CONSENT

The examination of patient was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

REFERENCES

1. Ideguchi H, Suda A, Takeno M, Ueda A, Ohno S, Ishigatsubo Y. Behçet disease:evolution of clinical manifestations. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90:125-32.

2. Leonardo NM, McNeil J. Behcet’s Disease:Is There Geographical Variation?A review far from the silk road. Int J Rheumatol. 2015;2015:945262.

3. Mazzoccoli G, Matarangolo A, Rubino R, Inglese M, De Cata A. Behçet syndrome:from pathogenesis to novel therapies. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16:1-12.

4. Gündüz O. Histopathological Evaluation of Behçet’s disease and identification of new skin lesions. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:209316.

5. Davatchi F. Diagnosis/classification criteria for Behcet’s disease. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:607921.

6. Asemota E, Slaught C, Micheletti R, Kovarik C. Optimizing “best available“medical options when practicing complex medical dermatology in resource-limited settings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:e171-2.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Comments are closed.