Doctors’ Support – An important part of medical therapy and quality of life

Mariusz Jaworski

Department of Medical Psychology, Medical University of Warsaw, ul. Żwirki i Wigury 81A, 02-091 Warszawa, Poland

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The correct patient – doctor relationship is important in shaping the whole process of treatment. The scientific studies highlight the various irregularities in this relationship and its negative impact on the effectiveness of medical treatment. The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between levels of doctors’ support and attitude to certain aspects of the treatment process and quality of life among patients with psoriasis.

Material and Methods: The study was conducted on 50 patients with psoriasis aged from 21 to 78 who are treated in dermatological clinics. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) was used to assess the severity of psoriatic skin changes. The patients completed a questionnaire for the assessment of receive doctors’ support, and its relationship with the attitude towards the disease. The research tool was developed based on literature review.

Results: The level of doctors’ support had a direct impact on the patients’ attitude the disease, including attitudes towards the treatment and medical personnel, as well as adherence to medical recommendations; and indirectly on satisfaction with the treatment and the quality of life.

Conclusions: Results of this study have shown clear evidence the importance of the level of doctors’ support in psoriasis which could help to improve the overall functioning of these patients. The level of doctors’ support indirectly affects the quality of life in patients with psoriasis.

Key words: Doctors’ Support; Quality of life; Psoriasis; PASI; Treatment

INTRODUCTION

The Health Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)is emphasized as a factor associated with the assessment of the effectiveness of medical treatment in recent publications. It is particularly importance in dermatology. The dermatological diseases are characterized by a significant impact on psychosocial functioning of the patients, which may affect their attitude the disease [1–3].

Psoriasis is a chronic disease characterized by a genetically determined inflammatory lesions of skin with periods of relapse and remission. The etiology of this disease is very complex. Four major factors contribute to the development of this disease: autoimmune, genetic, hormonal and psychosomatic. It is diagnosed on the basis of observable skin changes and its treatment is one of the most difficult dermatological challenges. Psoriasis typically manifests as red scaly rashes and itching. The treatment is generally external (specific and nonspecific), general (including retinoid, immunomodulating and cytostatic drugs)and physical (including photo chemotherapy, phototherapy, heliotherapy)[4–5].

The scientific reports suggest that the quality of life of patients with psoriasis is largely dependent on a number of clinical parameters, include severity of skin changes [6–8]. The greater the number and severity of skin changes, the worse the quality of life is. The effectiveness of the dermatological therapy may has a positive impact on improving the overall psychosocial functioning. The relationship between the severity of symptoms associated with chronic dermatological diseases and HRQOL is well documented [1–3,6–7]. It is important, to focus on the existence of factors which both directly and indirectly affecting the effectiveness of treatment of patients with psoriasis, and thus their quality of life.

In recent years, there is an emphasis on the biopsychosocial model of disease and identify a variety factors which may be important during the medical therapy. One of these factors is the patient – doctor relationship. The correct communication between the patient and doctor can significantly affect the patient’s attitude towards: (1)the disease, (2)the process of treatment and (3)medical workers. This may be associated with the quality and quantity of showing doctors’ support and the degree of understanding of the needs or/and patients’ problems [9,10]. Avoiding the patients’ depersonalization and increasing the empathy, at the same time, could develop a positive attitude towards the patients’ disease and the treatment process. The attitude towards the disease consists of three components: cognitive, emotional and behavioral. Changing of one of these factors may change the other components, thereby to change the attitudes towards the disease. Causing changes in affective state could influence the extent of behavioral activity of patients which is takes with respect to his/her disease [9–11].

The correct patient – doctor relationship is important in shaping the whole process of treatment. The scientific studies highlight the various irregularities in this relationship and its negative impact on the effectiveness of medical treatment. In many cases, the doctors believe that professional approach to the patient is limited to the diagnosis and the selection of appropriate pharmacotherapy. In contrast, the empathic approach to patients’ problems, both medical as well as psychological, often is treated very superficially. The doctors do not give these problems a lot of time. The multi-faceted approach to reported intrapsychic problems may be particularly important in dermatology [9–11].

The skin is an important element of non-verbal communication, which affects the quality of interpersonal communications, e.g. through the expression of emotions. The severity of skin changes may contribute to reducing the frequency of interpersonal contacts undertaken, as well as a negative impact on mental state and quality of life [13,14]. Consequently, the support of dermatologist becomes particularly therapeutic relevance.

The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between levels of doctors’ support and attitude to certain aspects of the treatment process and quality of life among patients with psoriasis. The following research questions were formulated based on the literature review:

- What is the level of doctors’ support among psoriasis’ patients?

- What is the level of quality of life in patients with psoriasis?

- Is there a relationship between the current level of doctors’ support and the patients’ attitude the treatment process?

- Is there a relationship between the current level of doctors’ support and the attitude of patients to adhere to the medical recommendations?

- Is there a relationship between the current level of doctors’ support and the attitude of patients to medical staff?

- Does the current level of doctors’ support affects patient’s satisfaction of the currently treatment?

- Does the current level of doctors’ support affects the quality of life of patients with psoriasis?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted on 50 patients with psoriasis aged from 21 to 78 who are treated in dermatological clinics. The mean age was 38.4 years (SD = 14.2). The group of subjects consisted of 30 women and 20 men. The empirical data was collected from January 2013 to December 2013. All patients who were participating in the study had a medical care. The subjects were recruited from patients who were:

- over 18,

- with diagnosed psoriasis,

- subject to ongoing therapy,

- and gave informed consent to be part of the study.

All patients gave informed consent.

Patients were examined dermatologically. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) was used to assess the severity of psoriatic skin changes. The PASI can range from 0 to 72 (where 0–lack of severity of symptoms and 72– severe of severity of symptoms) [15]. The currently used anti-psoriatic medication and the age at first diagnosis of psoriasis (years of life)were analysed.

The patients completed a questionnaire for the assessment of receive doctors’ support, and its relationship with the attitude towards the disease. The research tool was developed based on literature review. The patients assessed retrospectively the level of doctors’ support during diagnosis by a 5-point scale (where 1-complete lack of support, 2-small, 3-medium, 4-large, 5-very large). Before responding to the above question, we have asked to patients if they remembered how dermatologist gave them information about their diagnosis.

Then, the respondents were asked to indicate the current level of doctors’ support according to 5-point scale (where 1-complete lack of support, 2-small, 3-medium, 4-large, 5-very large). Subsequently, the participants of this study assessed the relationships between the current level of doctors’ support and various aspects of treatment, such as treatment process, adherence to medical recommendations, self-advancing our knowledge about psoriasis, well-being, the attitude towards the disease, the attitude towards the doctor and the treatment process. The respondents assessed the above dimensions of the attitudes toward the disease used by a 5-point scale, where -2-very negative influence, -1-negative influence, 0-neutral effect, 1-positive impact, 2-very positive impact.

The data were analysed statistically using Stat Soft Statistic 9.0 software. The p≤0.05 criterion of statistical significance was adopted. Since nominal, ordinal and interval scale data were analyzed, both parametric and nonparametric statistics were applied. Correlations between variables were analysed using the Spearman’s rank-order coefficient.

The statistical package IBM® SPSS® Amos 18 was used to developed a relationship models between the current level of support from the doctor, treatment satisfaction and quality of life of patients

Ethics

This study was performed on human subjects; thus, all patients were aware of the presence of the study and they were fully informed about the drug and its side-effects.

THE RESULTS

The study group was diverse in terms of marital status – 25.5% of patients declared free marital status, 59.0% were married and 15.4% were divorced. The age of onset of diagnosed psoriasis in the studied sample was between 9 and 45 (M=21.9, SD=13.2). Duration ranged from 1 month to 47 years (M=16.2;SD=11.9).

The PASI score in the entire sample ranged from 0.5 to 26.6 (8.86±0.8).

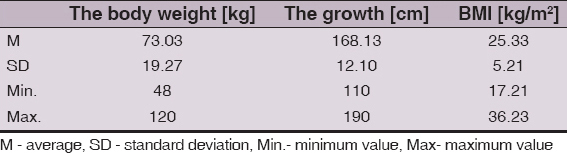

The body weight of patients was ranged from 48 to 120kg. The average value of weight in the analyzed group was 73.03kg (SD = 19.2). The BMI remained well within from 17.21 to 36.23kg/m 2 (Table. 1).

Table 1: The anthropometric parameters in the analyzed group

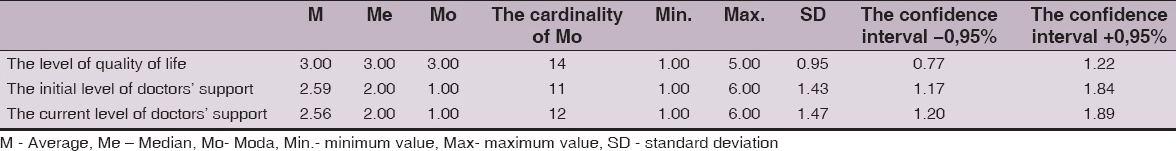

The quality of life of patients who were participating in the study was mediocre (Me = 3.00)(Table. 2). The largest percentage of respondents considered that their quality of life was average (35.9%). The slightly less patients felt that their quality of life was poor (30.8%)or good (25.6%). Only 5.1% of respondents admitted that their quality of life was very good, while 2.6% felt that it was very bad.

Table 2: The level of quality of life and the doctors’ support among patients with psoriasis

The initial level of doctors’ support during discussing diagnosis was assessed by patients as a small (Me =2.00). The current level of doctors’ support was also small (Me = 2.00)(Table.2). Changing the level of this support, which was assessed retrospectively, did not change during treatment of psoriasis (Z = 0.10; p = 0.92).

There was no correlation between the BMI and the level of quality of life in patients with psoriasis (rho = – 0.19, p = 0.12). It has been shown a negative relationship between the level of quality of life and the value of the PASI coefficient (rho = – 0.90, p = 0.01). In the next step of statistical analysis, we have assessed relationship between the change of the current level of doctors’ support and the length of psoriasis treatment. The statistical analyzes showed a positive relationship between those variables by use of the Spearman coefficient (rho = 0.32; p = 0.05).

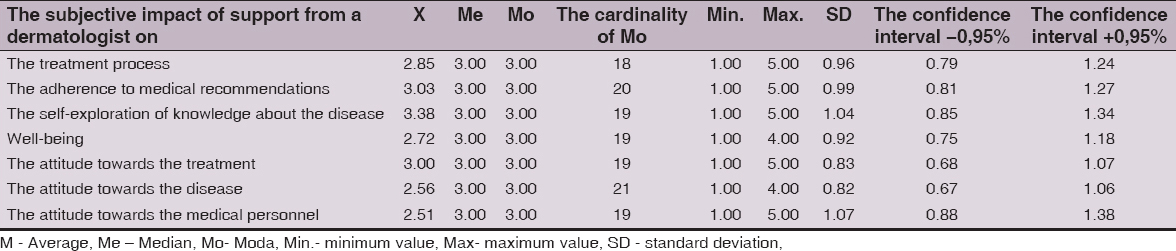

The subjective assessment of the impact of current doctors’ support on the various aspects of the treatment process had been made from the perspective of the patient. The current doctors’ support has no effect on treatment process (Me=3.00), well-being (Me=3.00), attitude towards to the disease (Me=3.00), and medical personnel (Me=3.00)in the opinion of the patients. The received doctors’ support, according to the respondents opinion, did not affect adherence to medical recommendations (Me=3.00)and attitude towards the treatment (Me=3.00), as well as the self-exploration of knowledge about the disease (Me=3.00)(Table. 3).

Table 3: Impact of doctors’ support on selected dimensions the attitudes towards the disease

The relationship between the current doctors’ supportand the various aspects of the treatment process, from the perspective of patients, were assessed in the present study which are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: The relationship between the level of doctors’ support and selected elements of attitudes towards the disease

The level of received doctors’ support at the time the diagnosis was positively correlated with the attitude towards the medical personnel (rho=0.30, p=0.03). There ware no such a compound in the case of the self-exploration of knowledge about the disease, the adherence to medical recommendations, the attitude towards the treatment and disease, as well as well-being (Table 4).

The current level of received doctors’ support has a positive relationship with the adherence to medical recommendations (rho = 0.61; p = 0.01), well-being (rho = 0.34; p = 0.02)and attitude towards the treatment (rho = 0.40; p = 0.01), the disease (rho = 0.32; p = 0.02)and medical personnel (rho = 0.43; p = 0.01)(Table 4).

It was also shown a positive relationship between the change of the level of doctors’ support and the adherence to medical recommendations (rho=0.47; p=0.01). The correlational dependencies have not observed in the case of the self-exploration of knowledge about the disease and the attitude towards the process of treatment, the disease and medical personnel (Table 4).

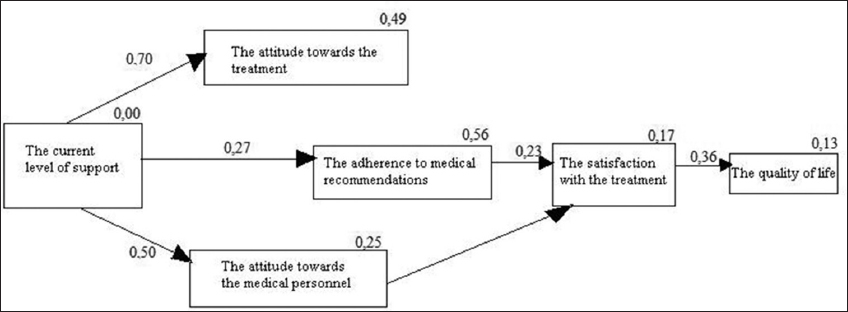

The evaluation of the relationship between the current level of doctors’ support and treatment satisfaction on one hand, and quality of life on other hand was assessed using analysis of structural equation modeling (SEM). The standardized regression weights assessing the strength of relationship between the variables showed a positive value for the level of doctors’ support and the attitude of the patient to treatment and medical personnel, as well as adherence to medical recommendations. The attitude toward the treatment was characterized by a direct relationship with adherence to medical recommendations, which directly affect the satisfaction of the actual treatment. The attitude toward the medical staff has showed a direct correlation with the degree of satisfaction with the treatment, and the attitude the treatment – intermediate with a degree of satisfaction with the current treatment. The level of satisfaction with the treatment had a direct impact on the quality of life of patients with psoriasis. The analysis of structural equation modeling has showed that the level of doctors’ support had a direct impact on the patients’ attitude the disease, including attitudes towards the treatment and medical personnel, as well as adherence to medical recommendations; and indirectly on satisfaction with the treatment and the quality of life (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: A model of the relationship between the level of doctors’ support and selected aspects of attitudes toward the disease in patients with psoriasis (χ2 (8) =3.72; p >. 05 (p = 0. 88); CFI=1.00 and RMSEA=0. 00; being removed the tracks that are not statistically significant).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that the level of doctors’ support has a direct in affect on the patients’ attitude towards the treatment process and adherence to medical recommendations. Numerous scientific reports have confirmed the relationship between the level of social support and good physical health [16–19]. A significant part of the studies concern the level of patients’ social support, centered around the family and the environment of live. The perspective of patient – doctor relationship is slightly less analyzed. These results suggest that the skills to show adequate levels of support may be important in the success of therapy.

The diagnosis of the disease is a stressful situation which could cause shock and loss of a sense of security.

Researchers who had analyzed human functioning in stressful situations – such as somatic illness – often referred to the theory of social support [6,20]. The skills for coping with a difficult situation is associated with a number of:

Informing about diagnosis is associated with stressful situation which could be partially reduced by correct communication doctor – patient; especially through an adequate level of doctors’ support, as well as the quality and quantity of information provided [21].

The cognitive psychology researches have shown the specificity of cognitive functioning – including memory, concentration, attention, perception – in a stressful situation [22]. This suggests that a minimum level of demand for information about disease determines the balance in the patient’s psyche. The affective aspect is also important among patients and doctors. The level of perceived severity of stress, affective state and cognitive processes may significantly affect the reception of the information provided by doctor and the desire to obtain the proposed medical treatment [22–23].

Restoration of patients’ sense of security may have a positive relationship with his attitude towards the disease process, treatment and adherence to medical recommendations [9, 24]. The empathic approach, doctors’ support and the ability to identify the patient’s expectations could play an important role in the restoration of patients’ sense of security [9]. The useful clinical tool in the assessment of the needs of the patient could be an motivational interviewing (MI).

Doctors’ Support influences not only on the attitude of the patient to the treatment process, but also to adherence to medical recommendations. The lower the level of support, the less medical recommendations adherence by patients. This highlights the importance of proper communication in the doctor-patient relationship during clinical practice.

It should be emphasized that the presented results of the study have a number of limitations that should be included during further empirical studies. Among other things, it is the small size of the group, which was not randomly selected. These limitations suggest caution in the interpretation of the data.

CONCLUSIONS

Results of this study have shown clear evidence the importance of the level of doctors’ support in psoriasis which could help to improve the overall functioning of these patients. The level of doctors’ support indirectly affects the quality of life in patients with psoriasis.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national)and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

REFERENCES

1. Hawro T, Maurer M, Hawro M, Kaszuba A, Cierpiałkowska L, Królikowska M, Zalewska A, In psoriasis, levels of hope and quality of life are linkedArch Dermatol Res 2014; 306: 661-6.

2. Blome C, Beikert FC, Rustenbach SJ, Augustin M, Mapping DLQI on EQ-5D in psoriasis: transformation of skin- specific health related quality of life into utilitiesArch Dermatol Res 2013; 305: 197-204.

3. Beikert FC, Langenbruch AK, Radtke MA, Kornek T, Purwins S, Augustin M, Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitisArch Dermatol Res 2014; 306: 279-86.

4. Jaworski M, Relationship between health behaviors and quality of live on the one hand and satisfaction with health conditions on the other hand in patients with PsoriasisOur Dermatol Online 2013; 4: 453-7.

5. Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY, Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practiceDermatol Online J 2014; 17: 20

6. Basavaraj KH, Navya MA, Rashmi R, Stress and quality of life in psoriasis: an updateInt J Dermatol 2011; 50: 783-92.

7. Inan?r I, Aydemir Ö, Gündüz K, Danaci AE, Turel A, Developing a quality of life instrument in patients with psoriasis: the Psoriasis Quality of Life Questionnaire (PQLQ)Int J Dermatol 2006; 45: 234-8.

8. McKenna SP, Lebwohl M, Kahler KN, Development of the US PSORIQoL: a psoriasis-specific measure of quality of lifeInt J Dermatol 2005; 44: 462-9.

9. Poot F, Doctor–patient relations in dermatology: obligations and rights for a mutual satisfactionJ Eur Acad Dermatol and Venereol 2009; 23: 1233-39.

10. Janowski K, Steuden S, Pietrzak A, Krasowska D, Kaczmarek L, Gradus I, Social suport and adaptation to the disease in men and women with psoriasisArch Dermatol Res 2012; 304: 421-32.

11. AlGhamdi KM, Almohedib MA, Internet use by dermatology outpatients to search for health informationInt J Dermatol 2011; 50: 292-9.

12. Demirel R, Genc A, Ucok K, Kacar SD, Ozuquz P, Toktas M, Do patients with mild to moderate psoriasis really have a sedentary lifestyle?Int J Dermatol 2013; 52: 1129-34.

13. Valenzuela F, Silva P, Valdés MP, Papp K, Epidemiology and Quality of Life of Patients With Psoriasis in ChileActas Dermosifiliogr 2011; 102: 810-6.

14. Magin PJ, Pond CD, Smith WT, Watson AB, Goode SM, Correlation and agreement of self-assessed and objective skin disease severity in a cross-sectional study of patients with acne, psoriasis, and atopic eczemaInt J Dermatol 2011; 50: 1486-90.

15. Louden BA, Pearce DJ, Lang W, Feldman SR, A Simplified Psoriasis Area Severity Index (SPASI)for rating psoriasis severity in clinic patientsDermatol Online J 2004; 10: 7

16. Körner A, Fritzsche K, Psychosomatic services for melanoma patients in tertiary careInt J Dermatol 2012; 51: 1060-67.

17. Uchino BN, Social Support and Health: A Review of Physiological Processes Potentially Underlying Links to Disease OutcomesJ Behav Med 2006; 29: 377-87.

18. Fuller LC, Hay R, Morrone A, Naafs B, Ryan TJ, Sethi A, Guidelines on the role of skin care in the management of mobile populationsInt J Dermatol 2013; 52: 200-8.

19. Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE, From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millenniumSoc. Sci. Med 2000; 51: 843-57.

20. Davidsson S, Blomqvist K, Molin L, Mork C, Siqurqeirsson B, Zachariae H, Lifestyle of Nordic people with psoriasisInt J Dermatol 2005; 44: 378-83.

21. Haidet P, Paterniti DA, “Building” a history rather than “taking” one. A perspective on information sharing during the medical interviewArch Intern Med 2003; 163: 1134-40.

22. Mackenzie CS, Smith MC, Hasher L, Leach L, Behl P, Cognitive Functioning under Stress: Evidence from Informal Caregivers of Palliative PatientsJ Palliat Med 2007; 10: 749-58.

23. Ng DM, Jeffery RW, Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adultsHealth Psychol 2003; 22: 638-42.

24. Kivelevitch DN, Tahhan PV, Bourren P, Kogan NN, Gusis SE, Rodriquez EA, Self-medication and adherence to treatment in psoriasisInt J Dermatol 2012; 51: 416-19.

Notes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Comments are closed.